“It all happened so fast. I’m afraid to wake up, afraid it’s all been a dream.” – Elvis Presley, 1956

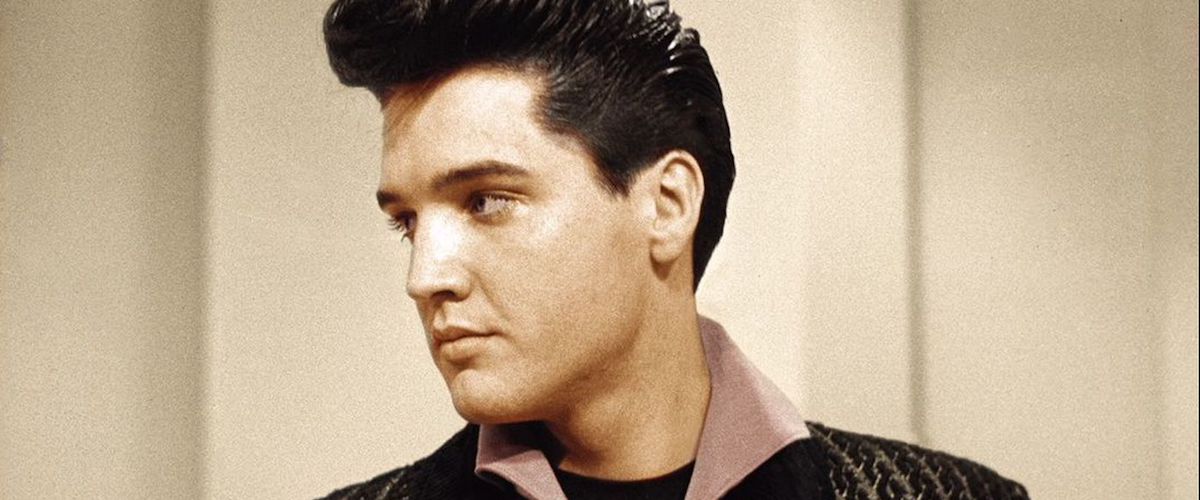

Elvis Presley’s image is so omnipresent in the culture it’s like a Coca-Cola logo on a billboard in Times Square. Only a few figures have achieved such gigantic posthumous fame. Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, and Judy Garland are all on this pretty short list. The image of the performer is almost completely detached from the details of what the career was actually about. This process occurred while Elvis Presley was still alive, since he became so famous so fast. In the press conference he gave before his Madison Square Garden concerts in 1972, he was asked if he was satisfied with his public image. Elvis, in a sky-blue suit with a jangling shiny belt, sideburns bristling down his face, replied, “The image is one thing. The human being is another. It’s very hard to live up to an image.” The image of Elvis shifts, depending on the entry point. What is so refreshing—damn near redeeming—about HBO’s two-part documentary “Elvis Presley: The Searcher,” premiering on HBO on April 14, is that the entry point is Presley’s art.

Produced with the full cooperation of Presley’s estate (Graceland opened its archives for the project), director Thom Zimny, along with writer Alan Light, shaped a narrative out of a vast amount of archival footage (home movies, press conferences, still photographs, movie and concert clips). In a way, what Zimny has done is chop away the jungle of gossip surrounding Presley: cars, women, peanut butter and banana sandwiches, karate, speed/opiate addiction, uncircumcised penis (sneered at by Albert Goldman in his appalling 1981 biography) … the list of “scandal” is endless. Lost in all of it is why people talk about Presley in the first place: his music and what it expressed. In collaboration with Priscilla Presley and Jerry Schilling, Presley’s friend from childhood, Zimny is interested in the spiritual and artistic forces which drove Presley from poverty to the heights of American success. Priscilla Presley observes, “[Elvis] wanted to grow. He wanted to evolve.” “The Searcher”—with its eloquent title—attempts to contextualize that lifelong process.

Zimny, brought onto the project on the strength of the many documentaries he’s done on Bruce Springsteen, made a couple of very important choices in “The Searcher.” He does not show the faces of the many subjects interviewed. This abolishes the dreaded “talking head” format, giving us space to engage with the images and flow of words. There are also repeating visual motifs, used in transitions: a boy riding his bicycle through rich green Southern fields, seen from high above. Later in the documentary, the bike has turned into a tail-finned gleaming Cadillac cruising through those same green fields. These are powerful poetic images, rich with symbolic significance. Beautiful shots from inside Graceland, reminiscent of William Eggleston’s famous photographs, are inserted throughout. They’re quiet still lifes: Elvis’ mother’s hairbrush, a china cabinet, the television in the front room, the view of the lawn from one of the windows. These are contemplative humanizing choices.

“The Searcher” moves in chronological order, hitting all of the major career sign-posts along the way: Sun Records, RCA Victor, the movies, the two gospel albums released in the 1960s, the 1968 “comeback special,” the album recorded at American Sound Studio produced by Chips Moman (who died in 2016), the 1972 Madison Square Garden concerts, the “Aloha from Hawaii” simulcast concert in 1973, the “jungle room” sessions in 1976, near the end, when Elvis no longer could get out of the house. Elvis’ personal life is present, but not foregrounded. “Elvis Presley: The Searcher” feels like a long overdue act of artistic redress.

The interview subjects range from those who knew Presley personally to knowledgeable passionate fans (Bruce Springsteen, Emmylou Harris, Tom Petty). Zimny has compiled extant interviews with key figures long dead (like Sam Phillips), as well as current interviews with music historians, Memphis historians, all of whom help explain Elvis’ background and influences. Stax songwriter David Porter provides essential context, not just to the whole period but how Elvis fit into it: “He would lose himself in an artistic way in order for people to feel it. That’s called soul.”

Another organizing principle of “The Searcher” is Elvis’ 1968 television special called, simply, “Elvis,” and now known (among Elvis fans) as “the ’68 comeback special.” For the majority of the 1960s, Elvis waited out his movie contract like a prison sentence, watching the British Invasion sweep the nation, leaving him behind. The television show, directed by Steve Binder, was initially conceived of by the Colonel as a Christmas special for the whole family to enjoy. But Binder and Elvis went about subverting the hell out of that, creating instead something explosive, personal, and practically avant-garde. It still feels ahead of its time. The stakes could not have been higher for Elvis in 1968. He wondered if the world had forgotten him. He hadn’t performed for an audience since a 1961 benefit concert in Hawaii to raise funds for the Pearl Harbor Memorial. Zimny goes back again and again to the special, at times letting the performance run in total. The group narration—from Steve Binder, from Priscilla Presley, from Jerry Schilling—has set us up powerfully. (“That special is imprinted on my memory forever,” says Springsteen.) In “Elvis Presley Blues,” Gillian Welch sings:

“And he shook it like a hurricane

He shook it like to make it break

And he shook it like a holy roller, baby

With his soul at stake.”

That’s what you see in the comeback special. A man with his soul at stake. Zimny does a magnificent job leading us through the maze of events in the 1960s to this defining and galvanizing moment, a moment still electrifying today.

Complicated subjects—like Elvis’ relationship with “The Colonel,” or the arrangement Elvis had with the Hill & Range music publishing company—are presented in a clear-cut fashion, providing fertile ground where understanding is given a chance to blossom. Elvis’ addiction to sleeping pills and speed (all prescribed by doctors) is not soft-pedaled, but the focus here is not “the sad life and thwarted career of Elvis Presley.” By digging into the specifics of certain recordings, Zimny and his chorus of experts provide a great educational service. So, for example: after many people share memories of Elvis working on his vocal range while he was in the Army, when we hear the second single he recorded after returning home, the operatic “Now or Never,” there’s a huge payoff. Zimny led us here to the moment of vocal triumph. He’s showed us how to listen.

Musician and writer Warren Zanes observes in “The Searcher,” “How do we know when we’re listening to a song that someone means it? The people who mean it are generally the ones who are processing some kind of loss through music—and we can hear them negotiating their loss, and we connect to it.” This is another way of saying Elvis was a man—from the very beginning—whose “soul was at stake.” Dave Marsh, also interviewed for “The Searcher,” closes his great 1982 book on Elvis with this ringing paragraph: “Elvis Presley was an explorer of vast new landscapes of dream and illusion. He was a man who refused to be told that the best of his dreams would not come true, who refused to be defined by anyone else’s conceptions. This is the goal of democracy, the journey on which every prospective American hero sets out. That Elvis made so much of the journey on his own is reason enough to remember him with the honor and love we reserve for the bravest among us. Such men are the only maps we can trust.”

“The Searcher” shows why these words are not hyperbole.