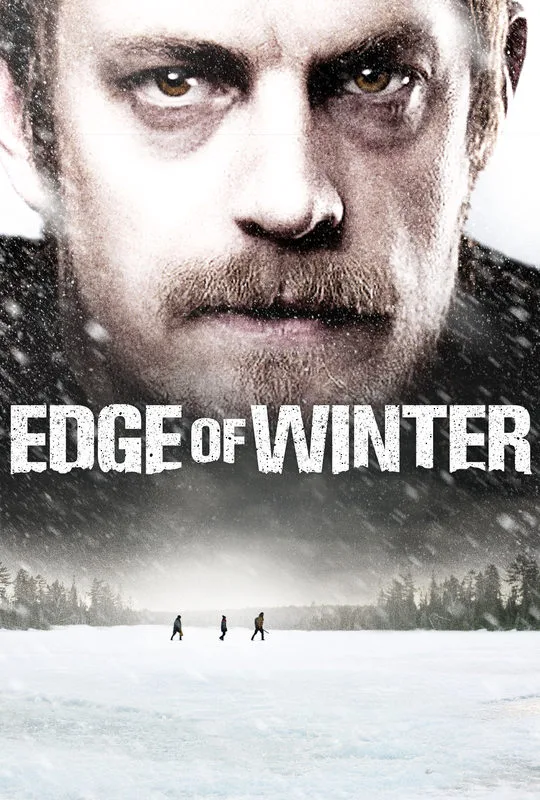

A psychological thriller of a familiar sort, Rob Connolly’s “Edge of Winter” does have things to recommend it to adventurous viewers: a very suspenseful, atmospheric mounting and sharp acting by its small but expert cast.

The tale’s premise is simple. Heading off on a winter vacation, a mom and her current husband deposit her two boys with her ex for minding while she’s away. Elliot (Joel Kinnaman), the dad, is a rugged, outdoorsy type, but he seems at home neither in his own skin nor in his new apartment, a shoebox that he’s landed in after being laid off from his job. Did he lose his employment because management was downsizing or because he’s too difficult to deal with? Though the question is never asked, the answer will come to seem all too obvious.

The two boys are neither overjoyed nor disappointed to be left with their dad. They know his complexities well enough, it would seem. The man has a temper, after all, and it suddenly erupts when one of the boys finds a rifle under a bed. But after Elliot cools off, he has an idea: The kids know nothing about guns, do they? Well, he’ll teach them. It’s a fatherly thing to do, and a subject young males should master. For the boys, this not only promises to be a bonding rite, but one with a hint of the forbidden: their step-dad would never offer it, and their mom would no doubt be horrified.

Out in the snowy Ontario back country, Bradley (Tom Holland), the older boy, is stunned to discover how strong the shotgun’s kick to his shoulder is. But he and his sibling, Caleb (Percy Hynes White), enjoy learning the basics of marksmanship. It’s an enjoyable outing, up until the boys’ tussling in the car as they depart sends it careening into a snow bank, where it gets firmly lodged.

With no civilization in sight, Elliot elects to lead the trio on a cross-country trek in search of help. But their compass-less hike only seems to lead them deeper and deeper into the wilderness, and the ordeal becomes life-threatening when Bradley falls through the ice of a frozen lake and flounders helplessly until his dad plunges in and saves him.

Fortunately, there’s an empty hunting cabin nearby and Elliot is able to build to a fire to take the chill off his and Bradley’s soaked bodies. But the three are still stranded in the middle of nowhere, and to make a bad situation even worse, the boys let slip a piece of news that they were meant to keep secret: their step-dad has gotten a new job in England and means to move the family there soon.

The thought that his boys will be taken from him in a way that seems both drastic and permanent stuns Elliot, and we can soon see where his thoughts take him: Rather than being rescued, maybe he and the boys could hole up out here in the wilderness and live off the land. Wouldn’t that be an adventure? Wouldn’t it be better than being separated across continents?

Thus, the dad who’s so avid to protect his kids suddenly becomes the main threat to their safety—a situation that gains a new wrinkle and heads toward a violent climax when other wayfarers happen upon the snowbound cabin.

Director Rob Connolly (who co-wrote the script with Kyle Mann) has an understated but sharply honed visual sense that keeps the drama taut and engaging throughout. The story’s psychological crux unfolds in a subtle and believable fashion. We can feel Elliot’s love for his sons; indeed, it’s so strong that when it flips into a mania that could spell their doom, that extremity of emotion is credible too.

The drama plays well, thanks to the expertly naturalistic performances Connolly gets from his main cast. As Elliot, Kinnaman displays an engaging mixture of tenderness and toughness, as well as the dangerous confusion of a man who comes to feel dispossessed. Playing the boys, Holland & White are amusing, sometimes touching foils for their dad; some of the film’s best moments are reaction shots of Elliot’s sons registering a mix of bafflement and wonder at something he’s said.

Finally, the Canadian winter scenery adds an element that should have its own appeal in the dog days of August.