Writer/director Sydney Freeland’s debut feature displays considerable restraint in its finale, although that determination only comes after witnessing an onslaught of complications that pile upon the movie’s trio of central characters. “Drunktown’s Finest” sets up plenty of pins and does so with a lot of noise and flash. That Freeland ultimately refuses to knock them down might seem like a detriment, but it’s not. The decision is admirable and unexpected, and for the first time in the movie, it allows us an understanding of these characters outside of the collection of external conflicts they must endure.

The movie is set in and around a Navajo reservation that’s adjacent to the town of Dry Lake, N.M. The opening narration, which comes from one of the movie’s central characters, describes it as “a place to leave,” not to live. She questions why anyone would choose to stay. Freeland opens the movie with a montage of the location and its inhabitants, summarizing the problems (poverty, gangs, incarceration) as well as some of the virtues (tradition, family, friendships).

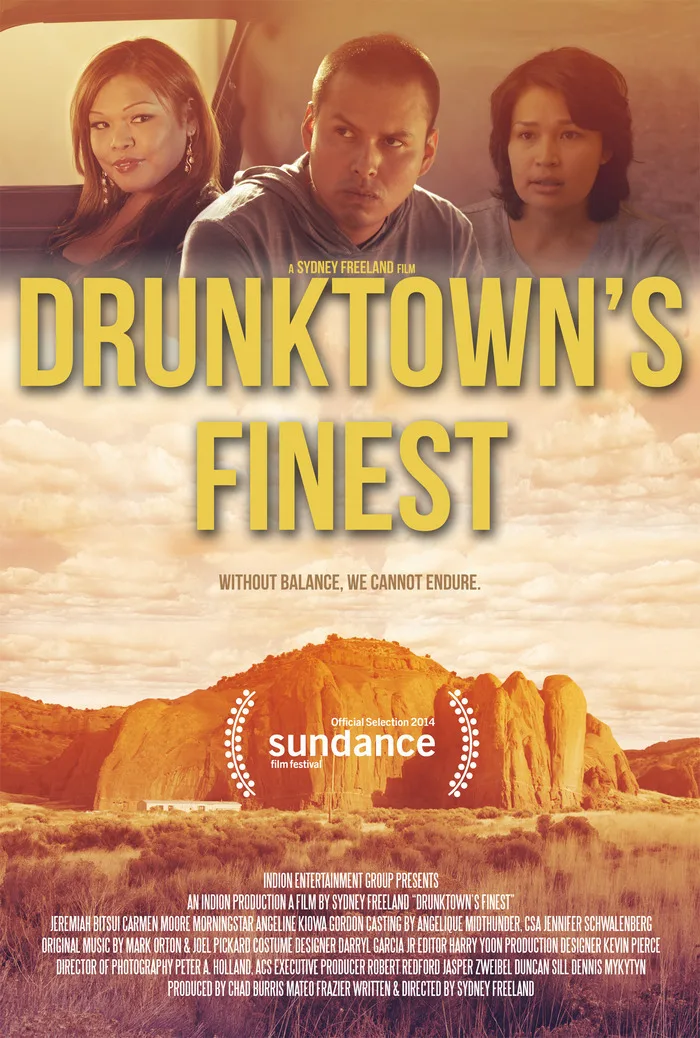

The opening narrator is Nizhoni (Morning Star Wilson), a former resident of the reservation who was adopted by a white couple at the age of 7 after her biological parents died. She has been attending high school in Michigan, is looking to remain in that state for college, and only returns to Dry Lake for summers. This summer, she’s trying to complete community service for a college scholarship. She also wants to uncover information about the family from which she came.

There is also Felixia (Carmen Moore), a transgender woman who lives on the reservation with her grandparents. In a pleasant surprise, her gender identity is simply, unquestioningly accepted by her family, although they have no idea that she earns a living from prostitution. Her grandfather (Richard Ray Whitman), the local medicine man, tells her the tale of how the third gender—the nadleeh—brought men and women together. When he learns she’s auditioning to model for a calendar of Navajo women, he only wants to ensure that she won’t be hurt in the process

The final character is Luther “Sick Boy” Maryboy (Jeremiah Bitsui). His first appearance comes after a drunken night out turns into an assault on a police officer. He’s scheduled to begin basic training for the Army at the start of the upcoming week, so his recruiting officer (Luis Bordonada) convinces the cop to drop the charges and gives Sick Boy one last chance to keep his act together. He wants to support his pregnant wife (Elizabeth Frances) and his little sister (Magdalena Begay), of whom he has guardianship, by joining the military, but he’s still tempted by drinking, drugs, and the criminal activity in which his friends engage.

These characters, of course, are connected in alternately arbitrary and inescapable ways. Sick Boy’s sister is preparing for a puberty ceremony, which is to be performed by Felixia’s grandfather. Felixia meets Sick Boy at a store, takes him to a party, and, during a drunken moment, makes sure his hand finds its way between her legs before their kissing goes any further. There really is only one option available as to the question of Nizhoni’s ancestry.

Freeland’s screenplay mixes tradition with superstition (a dead owl, one character notes, means death is coming), overt foreshadowing of problems to come with omens of impending doom (Nizhoni experiences déjà vu at the sight of a dead horse adorned with red handprints), and clunky expository dialogue establishing a heap of trouble for these characters. The last point is particularly true for Sick Boy, who is arrested twice, gets into two fights, nearly becomes involved in an armed robbery, and ends up with a man seeking revenge against him. It’s a clutter of half-realized ideas and fully calculated melodrama.

The performances here are generally unrefined, with most of the actors—including Wilson and Moore—barely going beyond rote line readings (Bitsui holds his own, although his character also has the heftiest load of conflicts with which to deal). There’s a certain quality of unforced, naturalistic charm to the performances at first (some of Freeland’s most egregiously explanatory dialogue would sound unnatural from even more experienced actors), but they become almost burdensome as the movie thickly lays on the conflicts.

The movie works in its quieter, less busy moments, especially during its domestic scenes. There’s a genuine sense of familial and cultural history when Freeland forgoes any of the story’s explicit obstacles and simply observes these characters going about their everyday lives. We get a glimpse of sincere conflict in a scene between Sick Boy and his wife, who admits that she’s relieved by the idea of her husband joining the Army, if only because it will mean “one less child” for whom she’ll have to care.

Despite the movie’s shortcomings, Freeland shows plenty of promise behind the camera. In those softer scenes, she shows a good deal of patience with and for her characters, and she displays an efficient eye for capturing these locales (complemented by Peter Holland’s fine cinematography). “Drunktown’s Finest” shows a filmmaker struggling to find her voice. It’s a whisper here, but we can hear it.