Actor and filmmaker Dany Boon is one of contemporary French cinema’s most prominent portrayers of the everyman, and when we see him in the driver’s seat of a taxi emerging from a car wash in the opening scene of this movie, we’re assured that we’re in good hands in at least one respect. Playing Charles, a driver in debt who’s also in danger of losing his license, his beard is light and his brow almost constantly furrowed. He’s got a job that he takes some pride in; when a know-it-all French exec (and they really are the worst kind) instructs him on his route, he ignores the orders, saying, “You do your job, I’ll do mine.”

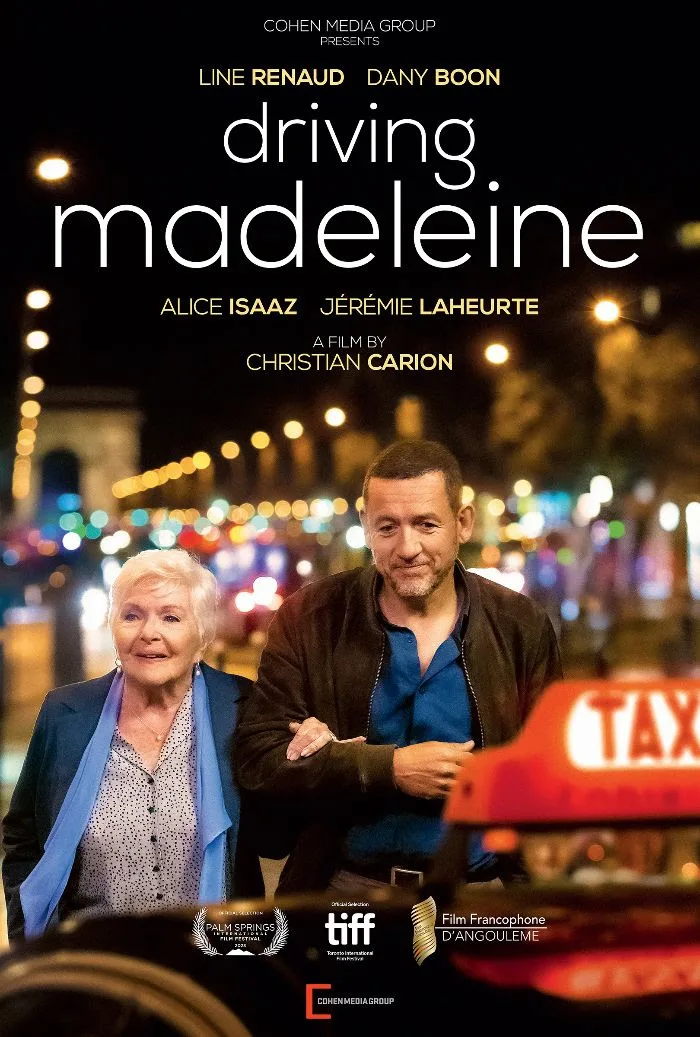

He gets a call telling him he can have a particularly well-paying fare, one that will take him across Paris and back—he’s instructed to turn on his meter as he goes to pick up the fare. The fare is the title Madeleine, played by Line Renaud, a chanteuse in her 90s whose showbiz adventures have included a stint on the American sitcom “Silver Spoons,” believe it or not. Madeleine is leaving her longtime maison for an assisted care facility—“One bone breaks and the whole machine goes on the blink,” she observes—and wants to take the long way there. So the viewer might strap themselves in for some life lessons.

“Driving Madeleine” does serve them up, sure, but the film, written and directed by Christian Carion, is a lot more than a sentimental journey. Carrion is best known in the States for his 2005 picture “Joyeux Noel,” based on a true account of a 1914 Christmas truce between German, French and British soldiers in World War I. His interest in 20th century history is resourcefully applied here. As Charles grudgingly lets the old woman begin reminiscing, we understand that she’s got to open up this man’s ears somehow. She knows he’s got a lot on his mind and he’s unhappy about whatever it is. “Anger ages you,” she advises. “But it’s everywhere now,” Charles says, loosening up a bit.

On one of their early detours, to Vincennes, she observes that nothing she remembers of the district remains. But through her words, she evokes vivid places and sensations. The flashbacks, sparsely lit and evocative, begin in the World War II era, and young Madeleine’s affair with an American soldier, which yields an illegitimate son.

Madeleine is pleasant and kind but as her tales demonstrate, she was not helpless. She marries a lustful mook, Ray, who resents the kid and begins taking his pathology out on both Madeleine and the child. “Back in those days, you couldn’t get a divorce for domestic violence,” she recollects. The young Madeleine, well played by Alice Isaaz, is compelled to go to extremes to deal with the situation, and there are consequences. As Carion’s camera acknowledges contemporary Paris landmarks—albeit not in a tourist-like way, thankfully—the movie’s storyline takes place in May ’68 and Vietnam, among other defining events, and does so without applying too heavy a hand.

In the world of today, Madeleine employs a wily strategy to wheedle out of a traffic violation that could cost Charles his livelihood. Their unlikely-by-definition friendship blossoms to the extent that the hard-up Charles even declines to insist on being paid his hefty fare immediately after the ride is over. Setting the movie up for a coda that’s not unpredictable but is wholly apt and satisfying.