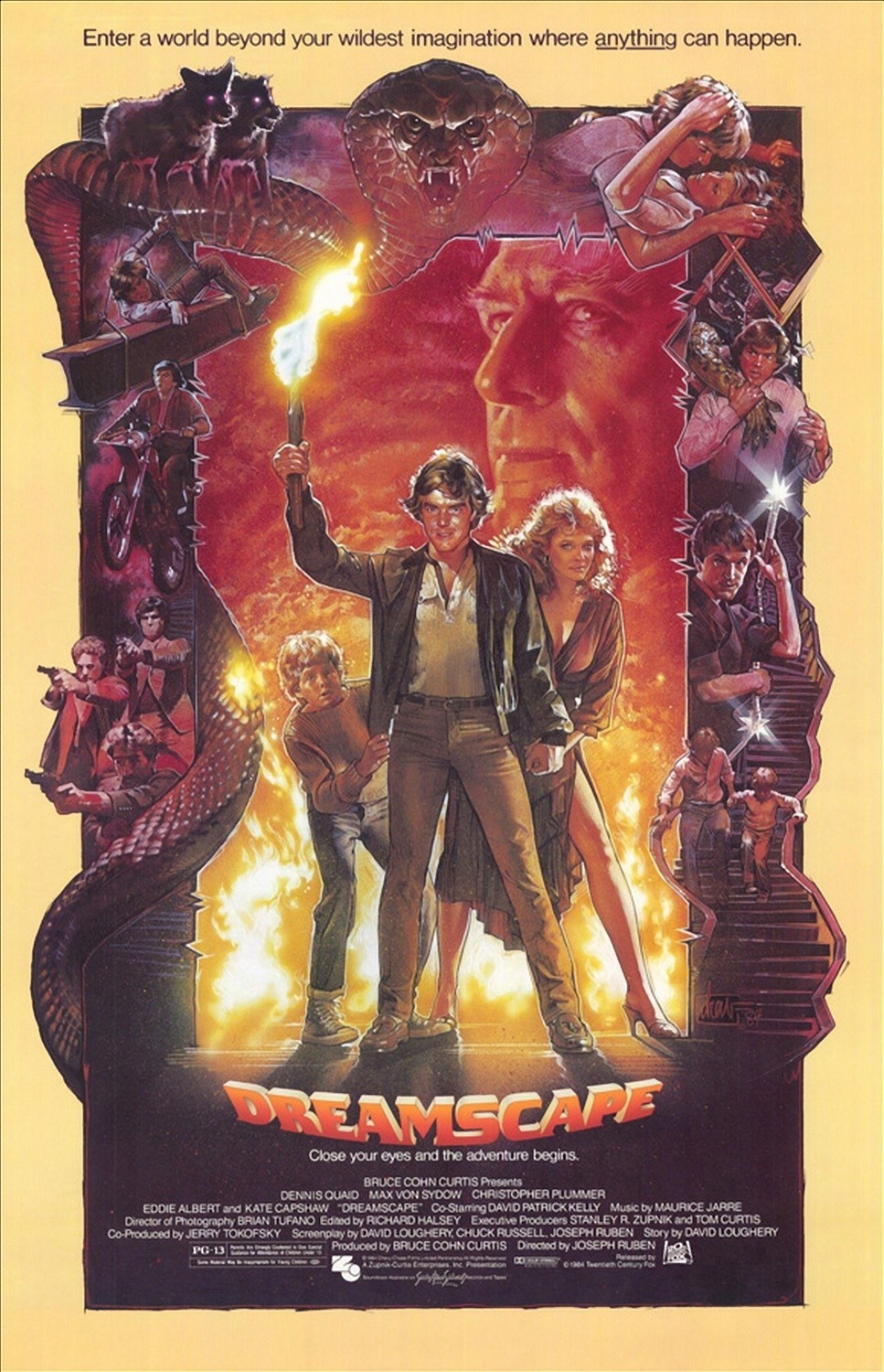

“Dreamscape” is three different movies, all fighting to get inside one another. It’s a political conspiracy thriller, a science fiction adventure, and sort of a love story. Most movies that try to crowd so much into an hour and a half end up looking like a shopping list, but “Dreamscape” works, maybe because it has a sense of humor.

The movie stars Dennis Quaid, that open-faced specialist in crafty sincerity, as the possessor of rare psychic powers. Once, years before, he had been the best ESP subject in the laboratory of a kindly old parapsychologist (Max Von Sydow), but then he disappeared. Now he is wanted again. The government is sponsoring explosive secret research in a brand new field: It believes there is a way for people to enter other people’s dreams. The possibilities are limitless. For example, a therapist could enter the nightmares of his clients and become an eye-witness to buried phobias. Jungians could rub shoulders with subconscious archetypes. Lovers could visit each other’s erotic dreams. And, of course, evil dreamers could drive their victims mad, or kill them with fright.

Quaid reluctantly agrees to become a subject for dream research, and almost immediately falls in love with von Sydow’s assistant, the healthy and cheerful Kate Capshaw, of “Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.” Then the plot thickens. Christopher Plummer turns up as the head of US “covert intelligence.” He is best friends with the president (Eddie Albert), who is, needless to say, having trouble sleeping these days. Albert has nightmares about starting World War III, and Plummer has nightmares that Albert will turn into a pacifist. He wants to use the dreamscape program to control the presidency. All of this plot stuff alternates with visits to people’s dreams, and it’s here that the movie gets interesting; movie dreams are usually clichés, and “Dreamscape” remains within the tradition, but comes up with some nice touches, including a crazy staircase that zig-zags into darkness and looks precarious and surreal. There is also a funny sequence in which Quaid discovers Capshaw taking a nap, and impudently enters her dream with lust on his mind.

The whole business about the plot against the president is recycled from countless other thrillers. Two things redeem it: The gimmick of the dream invasions and the quality of the acting. Science fiction movies routinely run the risk of seeming ridiculous, and with bad performances they can inspire unwanted laughs. “Dreamscape” places its characters in a fantastical situation, and then lets them behave naturally, and with a certain wit. Dennis Quaid is especially good at that; his face lends itself to a grin, and he is a hero without ever being self-consciously heroic.

As for the dreams themselves, as I watched the movie I found myself trying to remember some of my own dreams. The movie’s dreams include rooms with lots of windows and doors at crazy angles, railway coaches that are twice as wide as train tracks, and other visual distortions. I usually have more realistic dreams. Rooms and spaces have realistic proportions, and the distortions of reality come, not in the set decorating, but in the editing; flashbacks and intercutting points of view are not uncommon in my dreams, maybe because I see so many films. But movies can’t use flashbacks and view-point tricks to manufacture dreams — because then the movie would look like a movie and not like a dream. So the movies have created a conventional dream language. What “Dreamscape” does is enlarge it with brief, sometimes funny little asides that do feel like dreams, as when Quaid is inside the nightmare of a little boy, and they’re running from a Snake Man, and they see an adult seated at the end of a long table, and the kid says, “That’s my dad. He won’t be any help.”