History is written by the victors, who are only concerned with covering their asses and mythologizing their glory. This is why the oral histories that have been passed down from generation to generation by African-American families remain so important. Black history is American history, but so often it has been corrupted, miscategorized, bowdlerized, or flat-out ignored in schoolbooks and classes. Erasure cannot be done to oral traditions, so long as there is someone alive to tell the tale and pass it on.

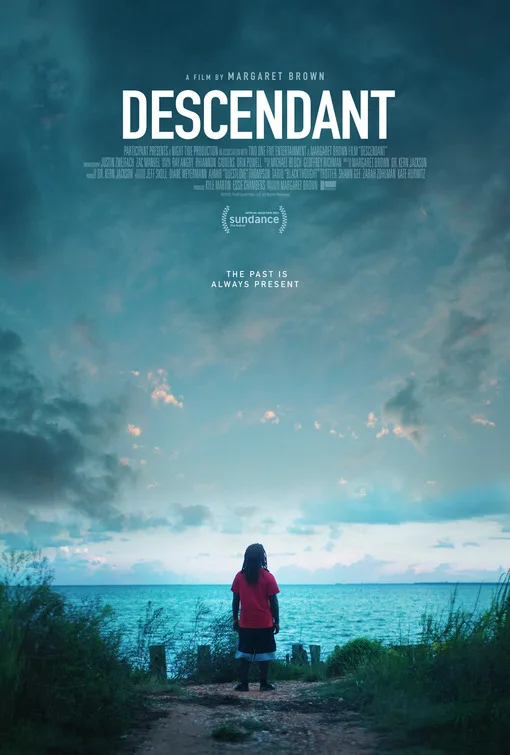

I thought about this while watching director Margaret Brown’s excellent documentary, “Descendant.” My beliefs were supported when I read Brown’s comments about the Clotilda, the slave ship that is her film’s narrative focus. “The story of The Clotilda was not a ‘myth’ or a ‘legend’ as it was often referred to by white people,” she wrote, “but an already present history, just one that was not told or accepted as the dominant ‘American’ narrative.” The ship, built and financed by wealthy Mobile, Alabama resident Timothy Meaher around 1856, was used to bring the last slaves acquired in the international slave trade to America in 1860. Since this type of slave trade had been deemed illegal in America, and was punishable by death, Meaher burned and sank The Clotilda afterwards to cover up his crime.

The descendants of the 110 victims of Meaher’s treachery settled in Africatown, a section of land now incorporated into Mobile, Alabama. The denizens there, past and present, were privy to the first-person narrative of Cudjoe Lewis, once believed to be the only living survivor of the Clotilda. Lewis told his story not only to his kin, but also to author Zora Neale Hurston, who wrote it down for her 1931 book, Barracoon: The Story of the Last Black Cargo. We hear Hurston singing some of the songs she learned from her research, and the film acknowledges that she is perhaps the first Black female film director. Written in Lewis’ vernacular, Barracoon was rejected by publishers and didn’t see the light of day until 2018. Meanwhile, everyone who lived in Africatown knew their ancestors’ stories, because oral traditions remain unaffected by the approved narratives peddled by the majority. Many Africatown residents held hope that proof of the Clotilda would someday be found.

“Descendant” begins with comments from a member of the National Association of Black Scuba Divers. There’s a possibility that the Clotilda has finally been located. We learn that its use as a slave vessel came from a bet Meaher made with another wealthy White man about whether he could pull off violating the 1807 ban on the international slave trade. The Clotilda’s captain, William Foster, sailed to what was then Dahomey, after Meaher heard that kingdom was selling its enemies into slavery. This puts “Descendant” in an intriguing conversation with the recent Agojie warrior film, “The Woman King,” which also takes place in Dahomey and mentions, though doesn’t explore fully, this aspect of the kingdom’s existence. (Full disclosure: I thoroughly enjoyed “The Woman King.”)

Several prior attempts to locate the Clotilda yielded erroneous results or none at all, due to location information that may have been purposely faulty. Reporter Ben Raines and business owner Joe Turner are attributed with locating the actual ship in 2019; their findings are certified by divers and National Geographic. Raines and Turner appear in “Descendant,” as do NatGeo archaeologist Frederik Hiebert and Slave Wrecks Project member Kamau Sadiki, who also works for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture (NMAAHC). Professor and folklorist (and the film’s co-writer) Dr. Kern Jackson, who studied the stories and lore surrounding the ship, is also on hand to provide important information to the viewer.

The most interesting talking heads are the descendants themselves. We meet several of them, including Emmett Lewis, a direct descendant of Cudjoe Lewis. Once the ship is found, these people have different things to say about how this historic find should be used. Some point out the historical importance and success of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, located in Montgomery, Alabama and visited by many tourists. Others don’t want this to just be an attraction; they believe its potential success as a historic site should also benefit the Africatown community. Indeed, one interaction between Emmett Lewis and a visitor to Cudjoe Lewis’ grave felt a bit too much like the guy was visiting a theme park attraction instead of someone’s grave. Lewis’ enthusiasm as he spoke proudly of his ancestor’s perseverance guided me through my mixed emotions and discomfort. “We’re still here,” he says proudly, and the claim resonated.

While “Descendant” shows the Africatown residents’ joy at finally having proof that the Clotilda is no legend, it also tells another story about systemic and environmental racism and how the Meaher family still benefits from the exploitation of the descendants of the 110 people Thomas Meaher stole and sold. Due to redlining and other corrupt zoning laws, Africatown is surrounded by factories that spew out toxic chemicals. It turns out that much of the land where these industries are located was leased or sold to them by Meaher family members. Even the bit of water where the Clotilda was found was the only part of the area owned by them and not by the Alabama government. Local environmental activist Ramsey Sprague explains that several residents correctly believe that their cancer or a relative’s cancer was due to years of living in the shadow of pipelines and smokestacks that billow chemicals into the air day and night.

No Meaher would go on record for Brown’s camera, but Michael Foster, a descendant of Captain William Foster, appears at the commemoration ceremony for the Clotilda findings. He is admittedly surprised by the lack of hostility and warm welcome he receives from the Africatown residents. He also takes a trip out to the area where the ship was sunk. During that excursion, Brown includes a conversation that drags out the tired and offensive idea that the “slaves were treated well” by their enslavers. That misguided excuse by descendants of slave owners might count as a form of an oral history if it hadn’t also been regurgitated in print for decades, if not centuries. The idea is politely shot down by another person on the boat.

Thankfully, “Descendant” doesn’t end with that scene. Instead, the film heads to the MNAAHC at the Smithsonian to spend time with one of the museum’s curators, Mary Elliott. Elliott curates the Slavery and Freedom exhibit, and tells her own story about an ancestor. It’s here that the full emotional brunt of “Descendant” hit me. On its own, this is one of this year’s best films, a superbly crafted and edited history lesson that benefits from letting its titular characters tell their stories. But what drew my tears was the kismet of my having finally gotten a ticket for the NMAAHC the week before my screening of this movie. I had been waiting six years to get in, and the experience was life-altering because I’d never been that physically immersed in Black history before. The closest I’d been to that feeling was when I was being told the stories of my own ancestors by family members.

“Descendant” is worth seeing no matter who you are. For viewers like me, however, it engenders the reality that, no matter how hard anyone tries to whitewash history, our stories will forever continue to be told in full, by us and for us.

On Netflix today.