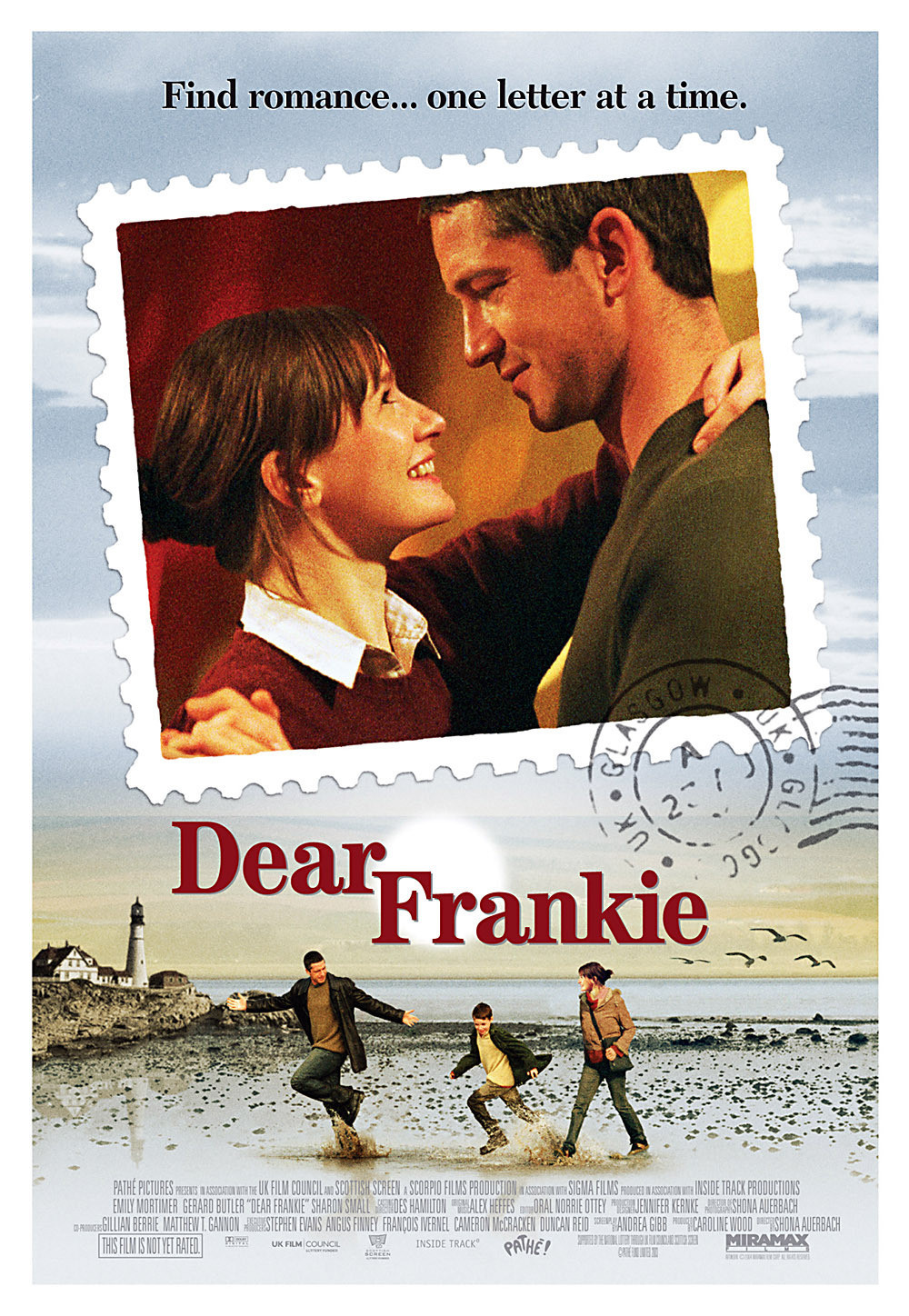

There is a shot toward the end of “Dear Frankie” when a man and a woman stand on either side of a doorway and look at each other, just simply look at each other. During this time they say nothing, and yet everything they need to say is communicated: Their doubts, cautions, hopes. The woman is named Lizzie (Emily Mortimer) and the man, known in the movie only as “the Stranger,” is played by Gerard Butler. Here is how they meet.

Lizzie has fled from her abusive husband, and is raising her deaf son, Frankie (Jack McElhone) with the help of her mother (Mary Riggans). Instead of telling Frankie the truth about his father, Lizzie creates the fiction that he is away at sea — a crew member on a freighter named the Accra. Frankie writes to his dad, and his mother intercepts the letters and answers them herself. Frankie’s letters are important to her “because it’s the only way I can hear his voice.”

The deception works until, one day, a ship named the Accra actually docks in Glasgow. Frankie assumes his father is on board, but a schoolmate bets his dad doesn’t care enough to come and see him. After all, Frankie is 9 and his father has never visited once.

Lizzie decides to find a man who will pretend, for one day, to be Frankie’s father. Her friend Marie (Sharon Small), who runs the fish and chips shop downstairs, says she can supply a man, and introduces the Stranger, who Lizzie pays to pretend to be Frankie’s dad for one day.

This sounds, I know, like the plot of a melodramatic tearjerker, but the filmmakers work close to the bone, finding emotional truth in hard, lonely lives. The missing father was brutal; Lizzie reveals to the Stranger, “Frankie wasn’t born deaf. It was a gift from his dad.” But Frankie has been shielded from this reality in his life and is a sunny, smart boy, who helps people deal with his deafness by acting in a gently funny way. When the kid at the next desk in school writes “Def Boy” on Frankie’s desk, Frankie grins and corrects his spelling.

“Call me Davey,” the Stranger says, since that is the name of Frankie’s dad. So we will call him Davey, too. He is a man who reveals nothing about himself, who holds himself behind a wall of reserve, who makes the arrangement strictly business. We follow Frankie and his “dad” through a day that includes a soccer game, and the inevitable visit to an ice-cream shop. At the end of the day, Davey tells Lizzie and Frankie that his ship isn’t sailing tomorrow after all — he’ll be able to spend another day with his son. This wasn’t part of the deal. But then Davey didn’t guess how much he would grow to feel about the boy, and his mother.

A movie like this is all in the details. The director, Shona Auerbach, and her writer, Andrea Gibb, see Lizzie, Frankie and his grandmother not as archetypes in a formula, but as very particular, cautious, wounded people, living just a step above poverty, precariously shielding themselves from a violent past. The grandmother gives every sign of having grown up on the wrong side of town, a chain-smoker who moved in with her daughter “to make sure” she didn’t go back to the husband.

Davey, or whatever his name is, comes into the picture as a man who wants to have his exit strategy nailed down. He insists money is his only motive. It is quietly impressive how the young actor Jack McElhone understands the task of his character, which is to encourage this man to release his better nature. There is also the matter of how much Frankie knows, or intuits, about his father’s long absence.

What eventually happens, while not entirely unpredictable, benefits from close observation, understated emotions, unspoken feelings, and the movie’s tact; it doesn’t require its characters to speak about their feelings simply so that we can hear them. That tact is embodied in the shot I started out by describing: Lizzie and the Stranger looking at each other.

“We shot several takes,” Emily Mortimer told me after the film’s premiere at Cannes 2004. “Shona knew it had to be long, but she didn’t know how long, and she had to go into the edit and find out which length worked. She is a very brave director in that way, allowing space around the action.”

Every once in a long while, a director and actors will discover, or rediscover, the dramatic power of silence and time. They are moving pictures, but that doesn’t mean they always have to be moving. At Sundance 2005 I saw Miranda July’s “You and Me and Everyone We Know,” and its scene where a man and a woman who don’t really know each other walk down a sidewalk and engage in a kind of casual word play that leads to a defining moment in their lives. The scene is infinitely more effective than all the countless conventional ways of obtaining the same result. In the same way, the bold long shot near the end of “Dear Frankie” allows the film to move straight as an arrow toward its emotional truth, without a single word or plot manipulation to distract us. While they are looking at each other, we are looking at them, and for a breathless, true moment, we are all looking at exactly the same fact.

Read Ebert’s interview with Emily Mortimer at Cannes 2004.