If there were 100 condemned prisoners on Death Row and one of them was innocent, would it be defensible to kill all 100 on the grounds that the other 99 deserved to die? Most reasonable people would answer that it would be wrong. Yet evidence has been gathering for years that far more than 1 percent of the inhabitants of Death Row are innocent. In the Illinois penal system, for example, a study following 25 condemned men ended after 12 of them had been executed, and the other 13 had been exonerated of their crimes after new evidence was produced.

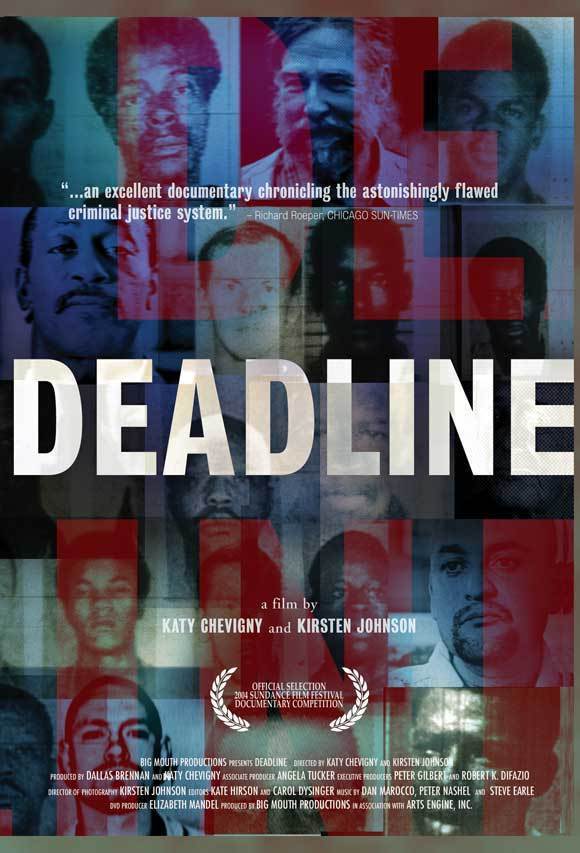

“Deadline” is a sober, even low-key documentary about how the American death penalty system is broken and probably can’t be fixed. It climaxes with the extraordinary January 2003 press conference at which the Republican Gov. George Ryan commuted the death sentences of all 167 prisoners awaiting execution in Illinois. His action followed a long, anguished, public process scrutinizing the death penalty in Illinois — a penalty here, as throughout the United States, administered overwhelmingly upon defendants who are poor and/or belong to minority groups.

The film opens with Ryan speaking to students at Northwestern University, where students in an investigative journalism class had been successful in proving the innocence of three men on Death Row. That was a tribute not only to their skills as student journalists but to the ease with which the evidence against the prisoners could be disproved. Many thoughtful observations in the doc come from Scott Turow, the Chicago lawyer and crime novelist who was appointed by Ryan to a commission to consider clemency for Illinois’ condemned. He is not against the death penalty itself, he says, and was completely comfortable with the execution of John Wayne Gacy, killer of 33 young men. “But can we construct a system that only executes the John Wayne Gacys, without executing the innocent?” Turow doubts it.

Murder cases have high profiles, and the police are under pressure for arrests and charges. They don’t precisely frame innocent people, the movie argues, but when they find someone who looks like a plausible perpetrator, they tend to zero in with high pressure tactics, willing their prisoner to be guilty. Confessions were tortured out of some of the Illinois prisoners in “Deadline,” including one who was dangled out of a high window by his handcuffs, and another who signed a confession in English even though he could not speak it.

The death penalty was briefly outlawed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972, and then reinstated in 1976 after the justices were persuaded the system’s flaws had been remedied. It was during that time, the movie says, that Richard M. Nixon “discovered crime as a national issue.” Before then, it had been thought of as a local problem and did not enter into presidential campaigns. After Nixon’s law-and-order rhetoric, politicians of both parties followed his lead. “All politicians want to be seen as tough on crime,” observes Illinois GOP House leader Tom Cross.

Since 1976 there has been a startling rise in executions in America, one of the few Western countries that still allows the death penalty. The movie cites statistics for American prisoners put to death:

1976-1980: Three executions.

1981-1990: 140 executions.

1991-2000: 540 executions.

That latest figure was enhanced by just one governor, George Bush of Texas; 152 prisoners were executed under his watch between 1995 and 2000, as Texas in five years outstripped the entire nation in the previous decade. In a speech, Bush says he is absolutely certain they were all guilty. For that matter, Bill Clinton must have known one of his Arkansas prisoners was so mentally retarded he asked the warden after his last meal, “save my dessert so I can have it after the execution.” But Clinton was running for president and dared not pardon this man, lest he be seen as soft on crime.

Some of the movie’s most dramatic moments take place during hearings before Ryan’s clemency commission, which re-heard all 167 pending cases. The relatives of many victims say they will not be able to rest until the guilty have been put to death. But then we hear testimony from a group called Murder Victims’ Families Against the Death Penalty. Among their witnesses are the father of a woman killed in the Oklahoma City terror attack, and the mother of the Chicago youth Emmett Till, murdered by Southern racists 50 years ago. They say they do not want revenge and are opposed to the death penalty.

“Deadline” is all the more effective because it is calm, factual and unsensational. There are times when we are confused by its chronology and by how its story threads fit together, but it makes an irrefutable argument: Our criminal justice system is so flawed, especially when it deals with the poor and the nonwhite, that we cannot be sure of the guilt of many of those we put to death. George Ryan, not running for re-election, faced that truth and commuted those sentences, and said he could live with his decision. George Bush was absolutely confident he was right to allow 152 prisoners to die. He could live with his decision, too.