A young woman runs and a pickup truck follows her. You can’t see who’s driving the truck, because the two people inside it are wearing face-covering gas masks. They grab the runner and forcibly subdue her. The opening credits play throughout, and they don’t seem to leave anybody out. Soon after, the movie begins. This scene, and almost every one after it, was shot on 16mm film and in surprisingly long takes.

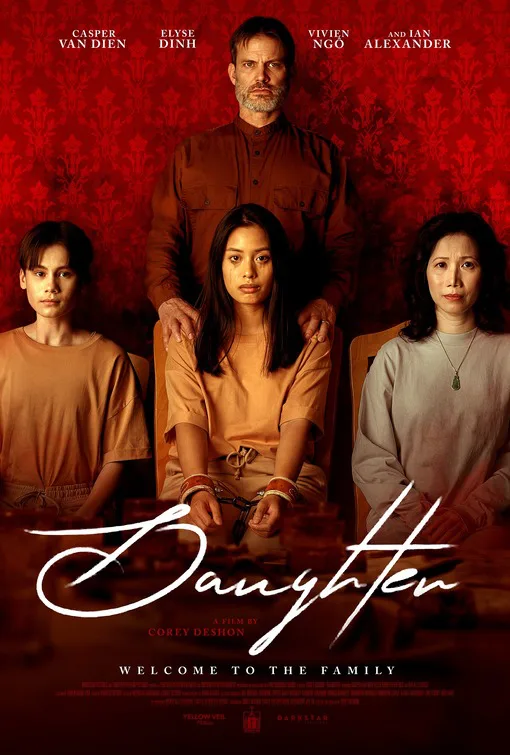

“Daughter,” an eccentric cult/hostage thriller, follows the two mask-wearing kidnappers, who self-identify as Father (Casper Van Dien) and Mother (Elyse Dinh), and their would-be victim, whom they call Daughter (Vivien Ngô). Father tells Daughter why he’s chained her up in his garage: his impressionable Son (Ian Alexander) needs a sibling, just for two more years. (It’s unclear why this matters despite a negligible explanation about Son and Daughter’s two-year age gap.) All will be well if Daughter fulfills her familial obligations and role-plays along with her new family. Father might otherwise turn violent, and while he says he doesn’t want to, the opening chase suggests otherwise.

Mother reassures her Daughter in Vietnamese. This early conversation seems to go on for longer than it should, but the silences that punctuate Dinh’s speech only deepen the unsettling mood established by a wide-angle master shot, which highlights the sheer size and emptiness of Father’s garage. Natural light, some film grain, and an unusual focus on uncomfortable silences give “Daughter” a superficial poise and a sense of mystery. So what’s wrong with this picture, and how do you play this family’s weird little game?

Father establishes some generic expectations and ground rules. He tells Son the world outside is sick, which also ostensibly explains his ominous home-schooling lessons. Mother prefers to go along to get along and encourages Daughter to do the same. (In Vietnamese: “It’s easier to give him what he wants.”) Son grins broadly and always tries to please Father. Daughter scatters seeds of mistrust by suggesting that she and her new Brother should collaborate on a play for his upcoming birthday. Father has his doubts—I mean, yeah—but allows his children to play by themselves. A strange, emotionally stillborn contest of wills ensues.

It’s sometimes hard to know where exactly “Daughter” is headed, though it’s obviously got something to do with storytelling and indoctrination. Van Dien’s dialogue is too flat and unyielding to be worth considering for long. He rails about critical thinking and casts judgment on the people outside his house, who could represent anybody from vax-compliant sheeple to anti-masking mavericks.

Writer/director/producer Corey Deshon pays increasing attention to Daughter’s sneaky attempts to influence her surrogate Brother through their scripted play, which they collaborate on secretly. But while this drama within the drama recalls “Dogtooth,” an acknowledged influence, nothing else about “Daughter” feels so distinctive.

Deshon gets a lot out of his ensemble cast members, even the relatively green Alexander, who puzzles over Daughter’s instructions like an excited puppy. Ngô stands out, especially in scenes where she tries and fails to connect with Dinh’s elusive Mother. These two Vietnamese-American actresses share an uncharacteristically tense conversation in the family’s kitchen. Deshon helps things along with some precise camera blocking, giving the scene the illusion of depth and character, since this stalled conversation is presented from over the characters’ shoulders and behind an island counter that separates the kitchen from the adjacent room. It’s suggestive, if not exactly meaningful.

Van Dien takes on the most thankless role in “Daughter.” He does very well as a rage case nutball, the kind of guy whose seething condescension makes even his most pseudo-placating dialogue threatening. At the same time, there’s so much of Van Dien’s Father in this movie that it’s often hard to connect with Deshon’s insinuating psychodrama. Only the most committed genre fans and academic-minded masochists will want to hang around until the bitter, arthouse-meets-choose-your-own-adventure style ending.

Still, “Daughter” has some promise, despite also seeming like a product of the same type of received wisdom it purports to rebel against. Dinh and Ngo are probably the two best reasons to watch “Daughter” though Van Dien remains the de facto star; Daughter has to essentially fight him for control of the movie’s lightly meta-reflexive narrative. Spending this much time with Father is a bit like being trapped on a road trip with a driver who monologues breathlessly just to get a few things off their chest and in a way that makes sense only to them. And as you listen to his long, fragmentary ramble, you feel your soul trying to escape your body as you struggle to imagine a satisfying end to this guy’s rant. “Daughter” is a long runway to a steep cliff.

Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms.