The key to a good interview is adaptability.

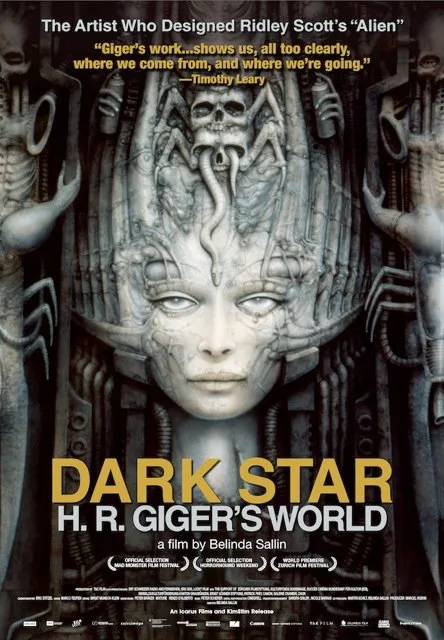

An interviewer can exhaustively prepare and research both their subjects and their audience, but no amount of preparation can fix things if something doesn’t work on the day of the interview. Documentary filmmaker Belinda Sallin is clearly familiar with the subject of her docu-character study “Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World” is, or at least familiar with the aspects of Swiss artist H.R. Giger’s work she most wanted to highlight. Sallin is also sensitive to the fact that she filmed Giger, the designer of the monster in “Alien” and the creator of numerous influential “bio-mechanical” works of air-brush art, when Giger’s health was ailing him at the age of 74. “H.R. Giger’s World” isn’t just remarkable because of Sallin’s appropriately existential focus on the people that regularly visited Giger during his final days. It’s also genuinely warm and involving because of the participation of everyone from Carmen Vega, Giger’s widow, to Sandra Berretta, Giger’s former assistant and self-described “life partner.” The film is, in that sense, an effective memorial, one filmed after Giger himself admitted that he had said all he wanted to say in his art.

In “Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World,” Sallin presents the artist as a ghost haunting his life. That may sound cruel, but that approach is, if anything, overly deferential. Sallin knows that Giger, even at the peak of health, was uninterested in explaining the themes and ideas behind his violent, sexually explicit work. Without an authorial guide, paintings and sculptures that depict wraith-like goddesses and monsters penetrating and being entered by various phallic objects are granted a genuine aura of mystery. Viewers can puzzle over, and even violently disagree with vague analysis made by Giger’s friends and loved ones, particularly agent Leslie Barany’s comment about the puzzling, maybe even divine, origins of Giger’s inspiration.

That intentionally mystifying approach suits Giger’s work. He only hints at possible mundane explanations for what drives him to make his art, saying that he painted his “Passages” paintings as a way to master real-life nightmares that prevented him from getting other work done. That need to control life through art is not unique to Giger’s career, so Sallin wisely makes it one of a handful of real-life inspirations. She doesn’t ask him about the literature—the plays of Samuel Beckett were one of many sources of literary inspiration—that inspired his work. But Sallin does briefly get Giger to talk about his relationship with Li Tobler, a troubled actress who inspired several of his paintings. These interviews are precious not because we get to see Giger talk candidly about a lost love, but rather because we get to trace another spider vein of influence on Giger’s art, one that may or may not run throughout Giger’s enormous body of work.

“Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World” does not, in that sense, set out to be a definitive portrait of Giger. We see him hovering around the periphery of his home while Sallin films his wife, his assistants, his cat, and his art. Giger’s work and influence are ingrained into our culture, so Sallin wisely doesn’t fixate on his work on “Alien” or waste time asking interview subjects to explain why they are drawn to one piece for another. Instead, Sallin’s film is an impressionistic reverie that encourages viewers by letting them marvel at Giger’s primal, staggering visions. You see Berretta commenting on Giger’s “Penis Landscape,” the infamous drawing that nearly bankrupted the Dead Kennedys after they included it as an insert in their “Frankenchrist” album, and were summarily charged with obscenity. Viewers of Sallin’s film are allowed to look at “Penis Landscape” without context, much in the same way that they’re encouraged to fill in the blanks of Giger’s relationship with Berretta, a well-spoken, unassuming expert witness.

Sallin’s light touch is admirable given the wealth of information at her disposal. Archival footage of Giger is used to convey feelings rather than intellectual conceits about Giger’s work: here he is on the set of “Alien,” and here he is a year or so before his health took a bad turn. You can see Giger’s elusive joie de vivre during both periods, a fact that speaks to Sallin’s humanistic impulse to treat the past with the same importance as the present. She also films Giger’s home and art with sophisticated crane shots and interior tracking shots for the sake of contrasting the small man with his towering work. Giger is, in that sense, treated as a single kernel from which rare and incredible work proliferated. His paintings are so viscerally demanding that they require viewers to pay strict attention to what is materially present on Giger’s canvas. By focusing exclusively on the present, “Dark Star: H.R. Giger’s World” only deepens the enduring mystique that surrounds Giger’s legacy.