There were times when “The Dangerous Lives of Altar Boys” evoked memories of my own Catholic school days–not to confirm the film, but to question it. There is a way in which the movie accurately paints its young heroes, obsessed with sex, rebellion and adolescence, and too many other times when it pushes too far, making us aware of a screenplay reaching for effect. The climax is so reckless and absurd that we can’t feel any of the emotions that are intended.

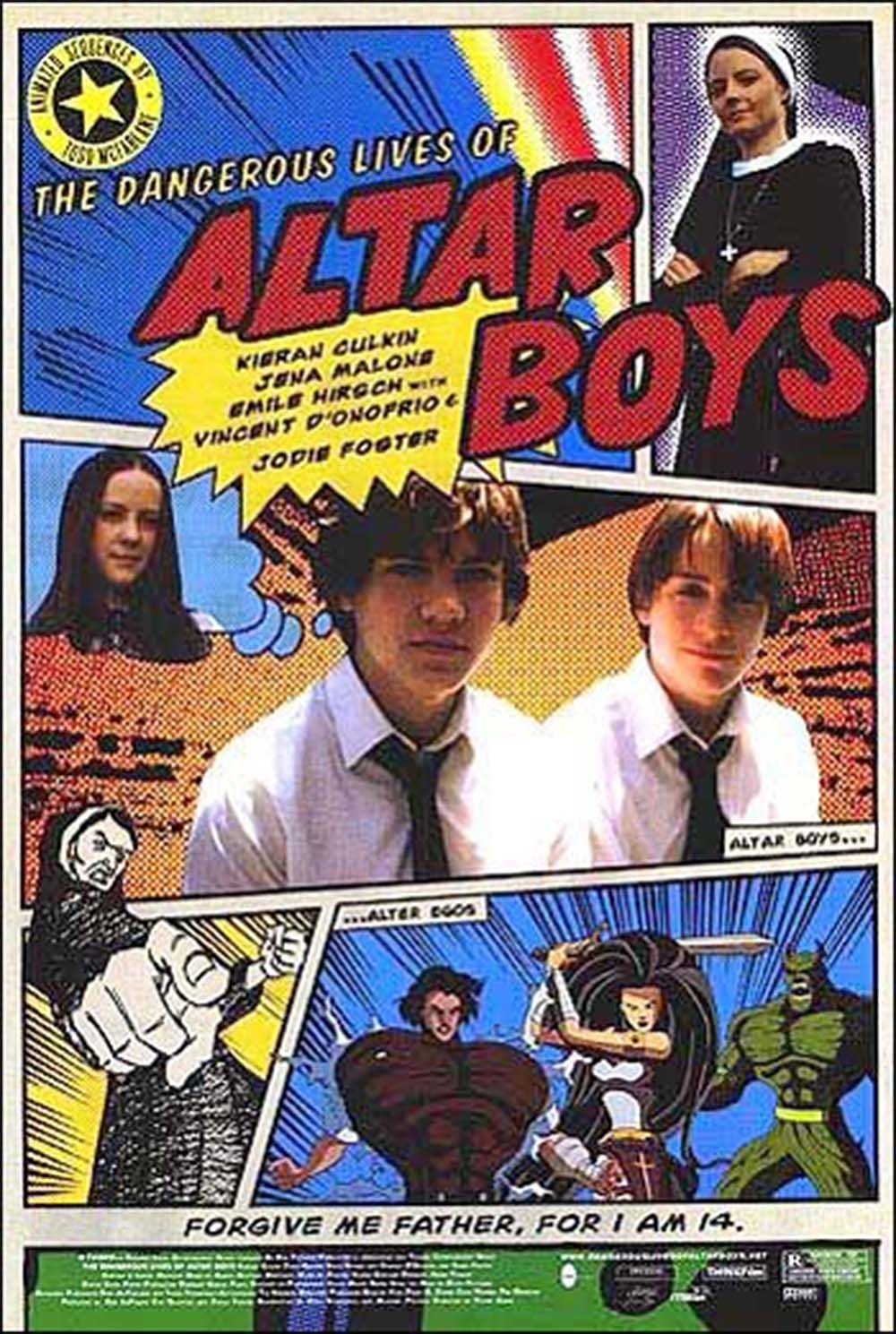

Yet this is an honorable film with good intentions. Set in a town in the 1970s, it tells the story of good friends at St. Agatha’s School, who squirm under the thumb of the strict Sister Assumpta (Jodie Foster) and devise elaborate plots as a rebellion against her. At the same time, the kids are growing up, experimenting with smoking and drinking, and learning more about sex than they really want to know.

The heroes are Tim Sullivan (Kieran Culkin) and Francis Doyle (Emile Hirsch). We look mostly through Francis’ eyes, as the boys and two friends weave a fantasy world out of a comic book they collaborate on, called The Atomic Trinity, with characters like Captain Asskicker and easily recognized caricatures of Sister Assumpta and Father Casey (Vincent D'Onofrio), the distracted, chain-smoking pastor and soccer coach who seems too moony to be a priest.

The movie has a daring strategy for representing the adventures of the Trinity: It cuts to animated sequences (directed by Todd McFarlane) that cross the everyday complaints and resentments of the authors with the sort of glorified myth-making and super-hero manufacture typical of Marvel comics of the period. (These sequences are so well animated, with such visual flair and energy, that the jerk back to the reality sequences can be a little disconcerting.) The villainess in the book is Sister Nunzilla, based on Sister Assumpta right down to her artificial leg.

Does the poor sister deserve this treatment? The film argues that she does not, but is unconvincing. Sister Assumpta is very strict, but we are meant to understand that she really likes and cares for her students. This is conveyed in some of Jodie Foster’s acting choices, but has no payoff, because the kids apparently don’t see the same benevolent expressions we sometimes glimpse. If they are not going to learn anything about Sister Assumpta’s gentler side, then why must we? The kids are supposed to be typical young adolescents, but they’re so rebellious, reckless and creative that we sense the screenplay nudging them. Francis feels the stirrings of lust and (more dangerous) idealistic love, inspired by his classmate Margie Flynn (Jena Malone), and they have one of those first kisses that makes you smile. Then she shares a family secret that is, I think, a little too heavy for this film to support, and creates a dark cloud over all that follows.

If the secret is too weighty, so is the ending. The boys have been engaged in an escalating series of pranks, and their final one, involving plans to kidnap a cougar from the zoo and transport it to Sister Assumpta’s living quarters, is too dumb and dangerous for anyone, including these kids, to contemplate. Their previous stunt was to steal a huge statue of St. Agatha from a niche high on the facade of the school building, and this seems about as far as they should go. The cougar is trying too hard, and leads to an ending that doesn’t earn its emotional payoff.

Another hint of the overachieving screenplay is the running theme of the boys’ fascination with William Blake’s books Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. I can believe that boys of this age could admire Blake, but not these boys. And I cannot believe that Sister Assumpta would consider Blake a danger. What we sense here is the writer, Jeff Stockwell, sneaking in material he likes even though it doesn’t pay its way. (There’s one other cultural reference in the movie, unless I’m seeing it where none was intended: Early in the film, the boys blow up a telephone pole in order to calculate when it will fall, and they stand just inches into the safe zone. I was reminded of Buster Keaton, standing so that when a wall fell on him, he was in the exact outline of an open window.) The movie has qualities that cannot be denied. Jena Malone (“Donnie Darko,” “Life as a House”) has a solemnity and self-knowledge that seems almost to stand outside the film. She represents the gathering weather of adulthood. The boys are fresh and enthusiastic, and we remember how kids can share passionate enthusiasms; the animated sequences perfectly capture the energy of their imaginary comic book. Vincent D’Onofrio muses through the film on his own wavelength, making of Father Casey a man who means well but has little idea what meaning well would consist of. If the film had been less extreme in the adventures of its heroes, more willing to settle for plausible forms of rebellion, that might have worked. It tries too hard, and overreaches the logic of its own world.

Note: The movie is rated R, consistent with the policy of the flywheels at the MPAA that any movie involving the intelligent treatment of teenagers must be declared off-limits for them.