The year is 1962. In the newly independent Republic of Mali, a civilian army—including women in matching blue dresses—train to use their new weapons as two civic leaders watch on the sidelines. One leader remarks how it reminds him of the French Revolution. Another rebuffs him, saying, “Shouldn’t we abandon French references?” “They’re international—international and universal,” the first retorts.

This is one of many moments in “Dancing the Twist in Bamako,” the latest film from French director Robert Guédiguian and co-writer Gilles Taurand, that feels as though the two are arguing for why they should be allowed to tell a tale of postcolonial Mali, when they both come from the colonizing country. This paternalism masked in white guilt hangs over the otherwise stylish and passionate film like a thick fog.

Inspired by the photography of Malian photographer Malick Sidibé, whose work captured the vibrancy of Malian youth during the early years of the nation’s independence under the leadership of President Modibo Keïta, the film aims to explore this tumultuous period through the age-old lens of star-crossed lovers. And while the filmmakers are able to mimic his slick aesthetic, the depth and weight of the lives behind the photographs are nowhere to be found.

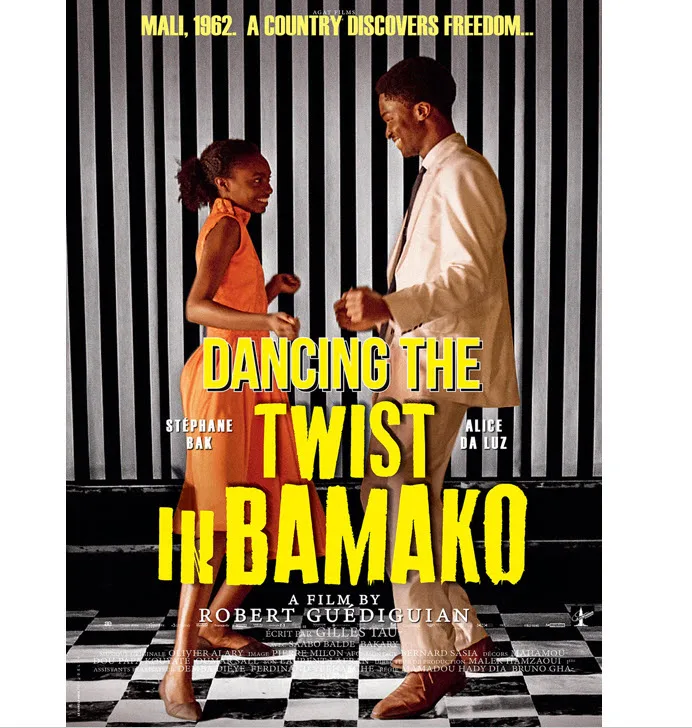

The charismatic Stéphane Bak stars as Samba, an idealistic young organizer who deeply believes in Keïta’s vision of African socialism, with Mali leading the way toward pan-African unity. On the way back to the capital city of Bamako after a mission to spread the government’s new socialist plans to a remote village, Samba finds a stowaway: Lara (Alice Da Luz, luminous), a spirited young woman from a lower caste who has been trapped in an arranged marriage and repeatedly raped by her husband. Bak and Luz have such wonderful chemistry that it’s really a pity that although the film ostensibly is centered on their romance, it’s so cluttered with plot threads and side characters that their heat quickly fades out of focus.

As their relationship grows, Samba begins pushing for greater social reform for women, including the abolishment of forced marriages. Yet, even his mentor Namori (Diouc Koma) feels those reforms can wait. They have more important missions to focus on at the moment, from getting schools built to explaining how collective farms work to getting rich traders to accept paying living wages to their workers. Somewhere in here, there’s an implication that this neglect early on has led to the current state of women’s rights in Mali, as implied by the film’s didactic final sequence in which we’re shown the stark differences in how women were allowed to dress in 1962 as opposed to 2012.

Although the movie is steeped in the politics of the era, it does little to actually interrogate the tensions at play for the characters. In the first village, Samba espouses the country’s new socialist plans in French—the language of the colonizers—but it only sinks in for the villagers after his compatriot translates what he said into Bambara. How does Samba feel about only speaking the colonizer’s language? If his entire raison d’être is to get his fellow countryman to unpack their colonial thinking, why does this moment not resonate on that level?

Similarly underbaked is the background of the youth clubs frequented by Samba, his younger brother, and later Lara. The kids dance to American rock and pop songs by Chubby Checker, Otis Redding, and the Supremes. Strict Eurocentric dress codes are enforced with young men in tight suits and women in short skirts and heels. This causes tension with the social leaders who think it will tempt the youth away from family values and traditions. But the film never bothers to explore why the youth are so drawn to the music, and especially the Eurocentric clothes. What feelings does it evoke for them? The tension between postcolonial freedom and the youth exploring this freedom through western iconography and culture goes mostly ignored.

Malian musician Boubacar Traoré’s song “Mali Twist” provided the title for the exhibition of Malick Sidibé’s photographs that later inspired the film. The song, whose lyrics translate to “Children of independent Mali, we must stand on our feet / Let all the young people return to their homeland / We must build the country together,” is featured as Lara gets measured for a new western style peach-colored dress, which she will later wear dancing and in portraits with Samba. Traoré’s music at the time was a blending of Delta Blues and his Mandé cultural roots, infused with the politics of the era. Yet, like Sidibé’s photographs, the deeper cultural connotations of the song and what it meant for the youth of the country are left unexplored. Instead, “Dancing the Twist in Bamako” remains a voyeuristic journey through the era, the filmmakers so enamored with the style they don’t bother with any substance.

Now playing in select theaters.