It is only now that I am in a condition to appreciate the 1950s.

At the time, I was too cynical. I read Mad magazine and listened to Stan Freberg and Bob & Ray, and viewed all manifestations of 1950s teenage culture with the superiority of one who had read Look Homeward, Angel and knew, even then, that you could not go home again.

Now things are different. Battered and weary after the craziness of the 1960s, the self-righteousness of the 1970s and the greed of the 1980s, I want to go home again, oh, so desperately – home to that land of drive-in restaurants and Chevy Bel-Airs, making out and rock ‘n’ roll and drag races and Studebakers, Elvis and James Dean and black leather jackets. Not that I ever owned a black leather jacket. Even today, I do not have the nerve. Black leather suggests a degree of badness I never could aspire to.

Feelings like these are what John Waters‘ “Cry-Baby” is about. The movie takes place in 1954, in Baltimore, at the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll (one is reminded of the opening scenes of “2001,” at the dawn of man, an event less remarked at the time). The teenage culture is divided into three camps: the drapes, the squares, and the nerds. The drapes slick their hair into ducktails and wear black leather jackets and are proud to be juvenile delinquents. The squares wear crew cuts and want to go to college. The nerds are not made much of in “Cry-Baby,” but in my memory they were the kids who wore slide rules in their pockets and collected science fiction magazines and grew up, one suspects, to be John Waters.

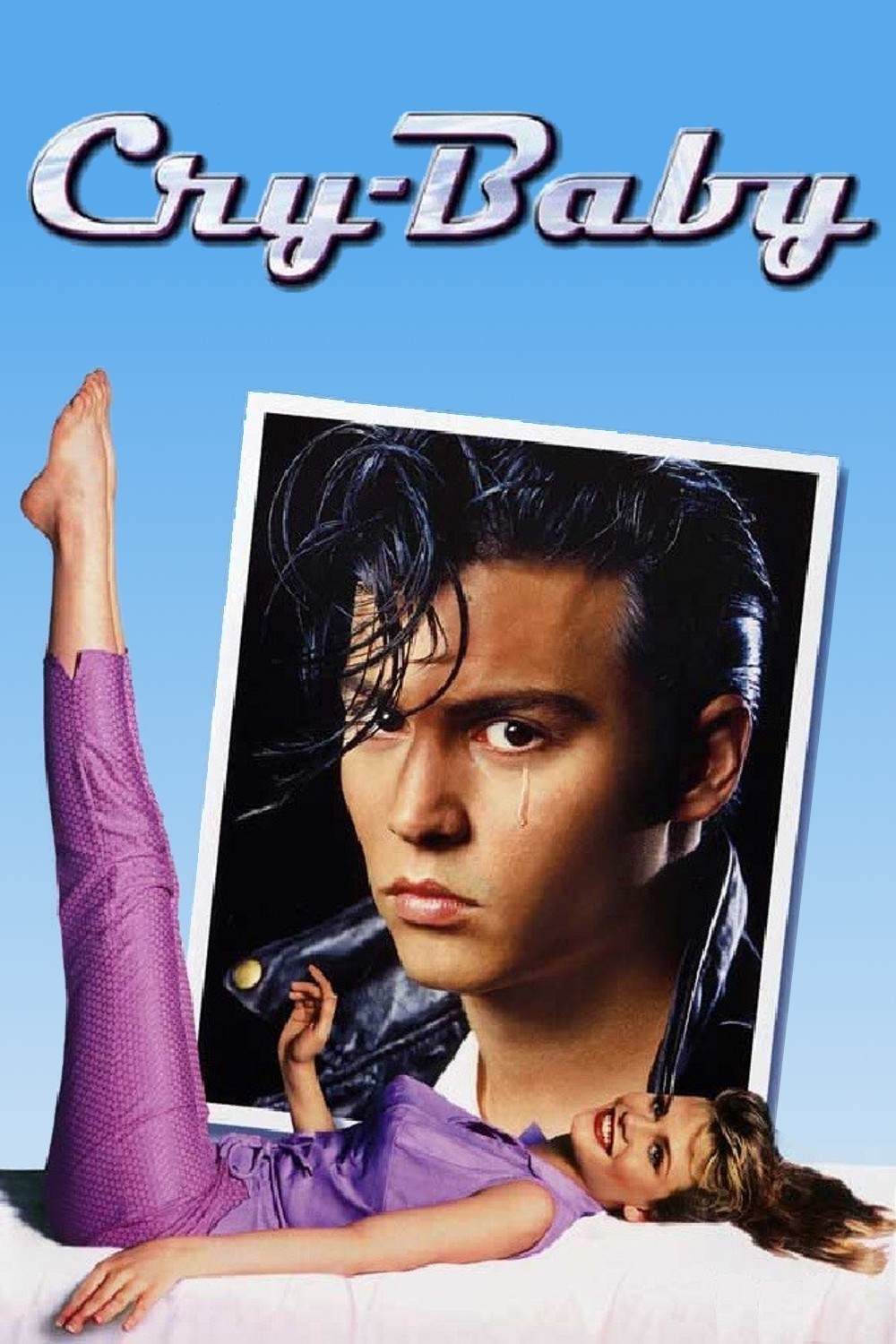

The movie tells the story of Cry-Baby himself, played by teen idol Johnny Depp as a juvenile delinquent who forever has a tear sliding halfway down his cheek, a reminder of a grief he will live with forever, a teenage tragedy that has left its mark on his soul, a lost romance. Into his life comes Allison (Amy Locane), the good girl who has a crush on Cry-Baby and feels strange stirrings in her loins by the promise that he is as bad as they say. The movie’s bad guy is the good guy, Baldwin (Stephen Mailer), who loves Allison in the right way, which is to say he loves her so boringly he might as well not love her at all.

The movie’s large cast (large enough to accommodate Polly Bergen and Traci Lords, David Nelson and Iggy Pop) includes Cry-Baby’s grandparents (Pop and Susan Tyrrell), a rockabilly family that lives on the wrong side of the tracks and musicians who seem to be on the edge of inventing rock ‘n’ roll, if some one does not invent it for them. It also includes various parents, schoolmates, local tramps and sluts, and the straight-arrow types without which the 1950s would have lost their point of reference.

If there is one constant in recent social history, it is that we feel nostalgia for yesterday’s teenage badness even while we fear today’s. As I was reading that ridiculous newsweekly cover story on rap music the other day, I found myself wishing that the hysterical old maids who wrote it could have been taken first to see “Cry-Baby,” so that they could gain some insight into themselves.

In every generation, teenagers find a way to express themselves and annoy adults. And the adults find in this teenage behavior signs of the collapse of civilization as they know it. “Cry-Baby,” which is a good many things (including a passable imitation of a 1950s teenage exploitation movie) is, above all, a reminder of that process. Today’s teenagers will grow up to be tomorrow’s adults, and yet in every generation teenagers and adults seem to have as little knowledge of that ancient fact as the caterpillar has of the butterfly.

It is an additional irony that humans have learned little from the insects, and the butterflies turn into the worms.