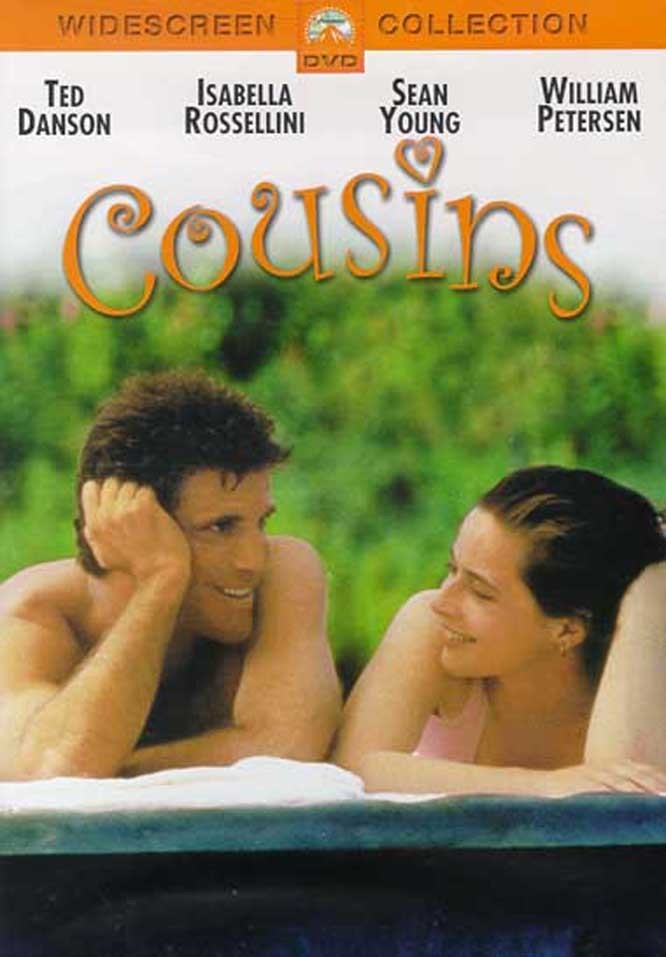

“Cousins” is a celebration of carnal desire, wrapped up in a comedy so that nobody is too badly hurt. In the real world, this kind of fooling around would turn family reunions into emotional bloodbaths, but here everybody smiles and the sun always seems to be shining.

Leaving the film, you start asking yourself what it was really about.

But while it’s playing you don’t think in those terms because you’re having too much fun.

The movie centers on three weddings, where a big, boisterous American family gets together for dancing, drinking, gossip and shoving matches. At the first wedding, two distant relatives (William Petersen and Sean Young) sneak off for a little hanky-panky in the middle of the afternoon. They return long after the party’s over, with some lame excuse about the car breaking down.

Their disappearance has given time for their spouses (Isabella Rossellini and Ted Danson) to meet each other, and to start to like each other. Danson is a job-hopper who teaches ballroom dancing, lives upstairs over a Chinese restaurant and isn’t too concerned about his wife’s possibile infidelity: “Everybody has to do what they feel they have to do.” But Rossellini does take it seriously, and the next day she tracks Danson down at his work to ask him if he thinks her husband and his wife are having an affair. This is, of course, the beginning of their own affair, although they’re not ready to admit that for awhile.

The movie is intelligently directed by Joel Schumacher, who places these two affairs in the center of a lot of detail. This isn’t one of those shallow movies that’s about nothing except love. Instead we get inside the lives of these people: Petersen as the womanizing BMW salesman, Rossellini as the woman who has stopped loving him but wants to be faithful to him, Danson as a warmhearted misfit, Young as a woman who wandered into the wrong marriage by mistake.

And there are some other family members who are very important to the action, especially Danson’s gruff old codger of a father (Lloyd Bridges), who has most of the best one-liners in the movie, and Danson’s punkster son from an earlier marriage (Keith Coogan). Acting as kind of a chorus in the background are Rossellini’s mother (Norma Aleandro), who loses one husband and gains another during the course of the movie, and Aunt Sofia (Gina DeAngelis), who is perfect as the bitter relative who attends every family event and mutters darkly in the background about everything she sees there (“That dress, you would wear to a hooker’s wedding”).

Rossellini and Danson are at the center of the story, however, because theirs is the romance based on true love, and they try, up to a point, to deny their feelings. And Rossellini is the key to everything.

She is so huggable in this movie, so funny, so sweet, that she brings sunshine into scenes that might otherwise seem contrived. She has one moment almost impossible to describe, when she and Danson have agreed to meet “accidentally” at a restaurant by bringing their families there. And as she looks up and is “surprised” to see Danson there, her joy and embarrassment and good humor all bubble up at once, and she almost breaks out laughing as she tries to go through with the charade.

Rossellini has the role in “Cousins” that was played by Marie-Christine Barrault in “Cousin, Cousine,” the warmhearted 1975 French comedy that inspired this Hollywood remake. Both actresses share some of the same qualities: sunny good humor and instinctive warmth in a merry, zaftig package. And they both have particularly winning smiles. Rossellini has been in only six or seven movies, and the one that made the biggest impression (the gothic comedy “Blue Velvet“) was scarcely designed to bring out her warmth. But “Cousins” could make her into a real movie star; she has the kind of qualities that audiences really respond to.

Danson is less perfectly cast as her lover. This is his most believable and likable role, and yet there is a certain reserve about him that never quite seems to lift, and maybe Petersen, who plays the other man, would have seemed warmer. Still, the material is so strong that we’re inclined to believe that if Rossellini likes him, she must know what she’s doing. Petersen is very good as the womanizing salesman, tormented by guilt but a sinner anyway. Young, as Danson’s wife, is brittle and distant; we never really get to know her.

We do, though, have a lot of fun with Bridges and Coogan as Danson’s father and son. Bridges has three or four lines that are explosively funny, and Coogan, a self-styled “video performance artist,” makes an avant-garde version of a wedding movie that brings things to a screeching halt.

“Cousins” is basically a rambling, warmhearted but artificial construction that seems more convincing because of the riot of life that surrounds the manipulated central characters. We don’t really believe what’s happening – adultery is never this simple, and seldom this life-affirming – but the movie gets away with murder because it’s funny, because the dialogue has been written with an ear for the funny things people say, especially when they’re being serious, and because of Rossellini.