If it’s a truism that the left-wing radicalism of the 1960s lives on mainly as a controlling ideology in the halls of academe, there’s an obvious corollary in the world of arts and media, where projects reflecting the same ideas and attitudes are propagated and justify themselves by–while never, ever questioning–the reigning academic orthodoxy.

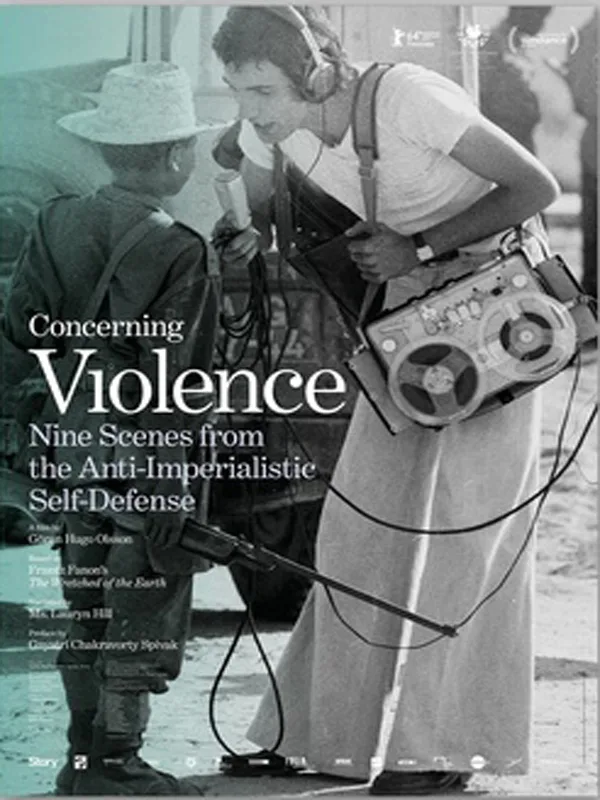

The latest example of this phenomenon, Göran Hugo Olsson’s “Concerning Violence,” begins, amazingly, with a static 10-minute lecture from an academic who tells us, in the most turgid and jargon-clogged terms, of the importance of what we are about to see. Seated at her desk, which is covered with stacks of book, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak comes billed as a “central theorist of post-colonial consciousness.” Her words may be intended to provide a bit of contemporary context for what follows, but they mainly serve to signal the filmmakers’ sense of their own political rectitude.

There is, indeed, much about “Concerning Violence” that wants to suggest it concerns real-world issues such as the struggles of Third World peoples to throw off the domination of colonial powers but ends up conveying more about the filmmakers’ self-regard and righteous feelings of “solidarity” with their radical forebears.

Subtitled “Nine Scenes from the Anti-Imperialist Self-Defense,” the film is not a documentary per se but rather an assembly of footage shot by Swedish news teams and political activists concerning the liberation struggles of various African countries, mainly in the 1970s. Framing and, in effect, commenting on these segments are excerpts from Frantz Fanon’s “The Wretched of the Earth,” which, during the film’s nine chapters, are emblazoned across the screen in emphatic lettering while being read by Lauryn Hill. (The fact that they’re in English rather than French, and are delivered by an American pop star, shows where the filmmakers’ commercial ambitions trump any desire for cultural authenticity.)

On both levels of the film, the archival and the textual, there’s much that’s fascinating and worthwhile. What’s regrettable is the refusal to contextualize and explore the ongoing ramifications of what we see and hear.

The archival footage, like much surviving 16mm of that era, has a purely sensory beauty, and it escorts us into lush landscapes where the conflict between haves and have-nots typically falls along racial lines. In the colonialist conclaves of Rhodesia and other parts of southern Africa, uniformed blacks at beautifully manicured country clubs serve cocktails to leisure-besotted whites, who sometimes speak with ugly, unvarnished frankness about their contempt for the natives and determination to hold onto their land and way of life no matter what the cost.

In jungles beyond these urban outposts, meanwhile, black revolutionaries forge rivers, set up camps and plan campaigns to take control of the lands where they were born. They speak eloquently about their aims. Particularly striking are the comments by a number of female guerillas, who seem to have thought a lot about sexual as well as racial and colonial politics in their attempts to educate themselves and understand their people’s struggles.

How did these movements originate? What happened to them after the moments when we glimpse them? How did they differ from nation to nation, region to region, tribe to tribe? How many achieved a liberation worthy of the name, or simply delivered their people into another form of tyranny? How many were genuinely self-directed as opposed to being heavily manipulated by the Soviet Union on one hand or the U.S. and European powers on the other? What do Africans think of them today?

These are among the many questions that “Concerning Violence,” while inevitably prompting, assiduously avoids addressing. The reason, perhaps, has to do with fashion. There’s long been a school of non-fiction filmmaking that rejects any form of talking heads, narration and other forms of commentary or explanation in favor of the “purity” of verité. And while there are surely subjects where such an approach is obviously appropriate, in a film like “Concerning Violence” it comes off as solipsistic–as if a certain aesthetic posture were more important than the clarity and detailed exploration the subject cries out for.

In effect, the film fetishizes its archival footage rather interrogating it (we hear nothing about the original filmmakers, their backers or how their work was used). It does much the same with Frantz Fanon, a fascinating, complex thinker whose groundbreaking work brilliantly explored the interface of psychology, sociology and revolutionary politics in colonial situations. Fanon’s words that “Concerning Violence” quotes remain powerful today. But how were they used and understood during the days of Africa’s liberation struggles, and how do they signify in the context of today’s Africa?

Fanon did see violence as a necessary tool in the fight against colonialism. But his thought has also been oversimplified, taken out of context and repurposed as a clenched-fist poster by people who have little interest its subtleties or its history. Such is the use it is put to in this film, which is less a thoughtful inquiry into certain very important subjects than sleek Scandinavian agit-prop that arrives four decades after its sell-by date.