12-year-old Ola is in charge of her household. She runs everything. She helps her autistic brother Nikodem get ready for school, she helps him tie his shoes, bathe, do his homework. She scolds her father Marek for going to the bar. She shops for groceries, cooks, cleans, does laundry. The family lives in a cramped two-room apartment outside of Warsaw. There is no mother in the picture, except as a voice on the other end of Ola’s constant calls, as Ola tries again and again to get her mother to attend Nikodem’s upcoming First Communion ceremony. The mother’s voice is tortuously vague and noncommittal. The burden placed on this child, the sheer weight of her responsibilities, is the subject of Anna Zamecka’s documentary, “Communion,” an astonishing directorial debut. Using a style both distanced and intimate, Zamecka enters so totally into this family’s routines and rhythms, that when Ola finally sobs, “I’ve had enough” it’s as though the film itself cracks apart, acknowledging the reality of what we’ve been watching.

Zamecka saw Marek Kaczanowski in a Warsaw train station, and was captivated by him as a camera subject. In the course of a conversation he told her about his children, Ola and Nikodem, and how proud he was of Ola for how well she took care of her brother and him. In this was the seed of “Communion.” Since the Kaczanowski apartment is so small, the camera could not be unobtrusive or invisible. The family’s uneasy awareness of the camera is part of the film. There’s a stripped-raw quality to so many of the scenes, and Marek and Ola display a hesitancy at what is being revealed. However, “Communion” is never exploitive. Zamecka films the family very tenderly. The only one really exploited here is Ola, used as free labor, labor that never stops. Halfway through the film, she’s shown at a middle-school dance, jumping around in a yellow dress, screaming out song lyrics with her friends, and it’s the first time we’ve seen her in a context where she gets to be a regular kid. She is like a different person.

Although “Communion” is a documentary, it is structured like a narrative feature, with an inciting event (Nikodem’s upcoming First Communion), a buildup of tension, an emotional cliffhanger (“Will the mother show up to the ceremony or not?”) and a denouement. Working with experienced editor Agnieszka Glinska, Zamecka crafted the film, its apartment scenes, its church and school scenes, into a coherent narrative with a strong throughline. When Ola rages through the apartment in her yellow dress, crying about how it’s a pigsty, it’s heartrending because of all we’ve seen of her before, how she works with Nikodem on his religious homework, quizzing him repeatedly, her seemingly uncomplaining acceptance of the sheer amount of work she has to do to keep the family afloat. “Communion” made me want to swoop in and save her, or at least give her a couple of weeks off so she could go hiking with her friends and have sleepovers.

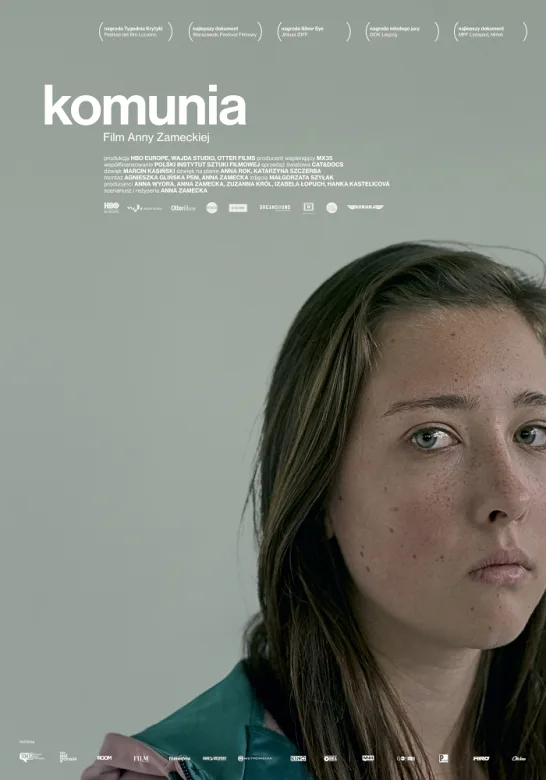

Zamecka and her cinematographer Małgorzata Szyłak set shots almost like portraits. The light falls on the family’s faces gently, Ola’s eyes going translucent, her paleness stark against the grimy surroundings. The camera remains static for the most part, a welcome change from the jangly hand-held style of so many documentaries. “Communion” opens with a beautiful shot of Nikodem attempting to put on his belt, talking to himself, laughing, sometimes smacking his head in frustration. Behind him is elaborate maroon flowered wallpaper, peeling off the wall. The camera is still. It’s a very respectful style. The camera doesn’t rove around the room looking for conflict, for reaction shots, to “up” the tension, all of the technical tropes that have seeped into the culture via reality television. Zamecka’s approach enforces a certain amount of distance from her subjects. We can see it all, how overworked Ola is, how helpless Marek is, how on top of one another they are in that apartment.

The First Communion preparation takes up the majority of the film, the family life organizing itself around the upcoming event. Nikodem has to be interviewed by a priest and Ola drills him on the answers he’s supposed to give. Because we know how much she hopes her mother will attend the Communion ceremony, her urgency that Nikodem “pass” all these tests is multilayered and fraught. There’s extreme symbolic resonance to all of this, what the sacrament of Communion symbolizes, the central place of the Church in Poland.

Nikodem is a difficult child, but also a positive kid, who enjoys animals and drawing. He is mainstreamed with other kids at school, and his special needs are not taken into consideration by his teachers. It’s painful to watch. At home, he goes into his own world, watching animal videos. His constant chatter fills the air behind other scenes, tense scenes between Ola and Marek, between Ola and the social worker who stops by for welfare checks. As Ola lies to the social worker, saying everything is going well, Nikodem’s voice floats in from the room beyond: “Endangered. Endangered. Female. Happiness. Happiness.” Zamecka’s quiet patient style allows for these “happy accidents” of life, where theme and reality dovetail. At one point Nikodem, taking a bath, playing with a dinosaur toy, says, out of the blue, “Reality becomes fiction.” It was so profound, not only a commentary on his life—but also on the film that was being made at that very moment—I wondered if I had even heard him right. Nikodem knows how to turn his reality into fiction. Ola can’t. If she doesn’t take care of Nikodem and teach him how to tie his shoes, who will? Nobody, that’s who. “Communion” does not push for an emotional response from the audience. It doesn’t have to.