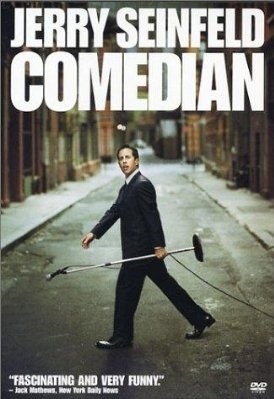

If it takes this much agony to be a stand-up comic, I don’t think I could survive a movie about a brain surgeon. “Comedian” follows Jerry Seinfeld and other stand-ups as they appear onstage and then endlessly analyze, discuss, rerun, regret, denounce, forgive and rewrite their material. To say they sweat blood is to trivialize their suffering.

It looks to the audience as if stand-up comics walk out on a stage, are funny, walk off, and spend the rest of the time hanging around the bar being envied by wannabes. In fact, we discover, they agonize over “a minute,” “five minutes,” “10 minutes,” on their way to nirvana: “I have an hour.” When Chris Rock tells Seinfeld that Bill Cosby does two hours and 20 minutes without an intermission, and he does it twice in the same day, he becomes very sad and thoughtful, like a karaoke star when Tony Bennett walks in.

Seinfeld can’t believe his good fortune. He reached the top, with one of the biggest hit TV shows of all time. And yet: “Here I am in Cleveland.” After retiring his old nightclub act with an HBO special, he starts from scratch to devise a new act and take it on the road to comedy clubs, half of which are called the Improv. He stands in front of the same brick walls, drinks the same bottled water, handles the same microphones as kids on the way up. Of course, he flies into town on a private jet that costs more than the comedy club, but the movie doesn’t rub this in.

Seinfeld is a great star, yet cannot coast. One night he gets stuck in the middle of his act–he loses his train of thought–and stares baffled into space. Blowing a single word can depress him. If it’s still a battle for Seinfeld, consider the case of Orny Adams, a rising comedian whom the film uses as counterpoint. Adams shows Seinfeld a room full of boxes, drawers, cabinets, file folders, stuffed with jokes. There are piles of material, and yet he confides, “I feel like I sacrificed so much of my life. I’m 29 and I have no job, no wife, no children.” Seinfeld regards him as if wife, children, home will all come in good time, but stand-up, now–stand-up is life.

Orny Adams gets a gig on the David Letterman program, and we see him backstage, vibrating with nervousness. The network guys have been over his material and suggested some changes. Now he practices saying the word “psoriasis.” After the show, he makes a phone call to a friend to explain, “I opened my first great network show with a joke I had never used before.” Well, not a completely new joke. He had to substitute the word “psoriasis” for the word “lupus.” But to a comedian who fine-tunes every syllable, that made it a new joke and a fearsome challenge.

Seinfeld pays tribute to Robert Klein (“he was the guy we all looked up to”). We listen to Klein remember when, after several appearances on “The Tonight Show,” he received the ultimate recognition: He was “called over by Johnny.” Seinfeld recalls that when he was 10 he memorized the comedy albums of Bill Cosby. Now he visits Cosby backstage and expresses wonderment that “a human life could last so long that I would be included in your life.” Big hug. Cosby is 65 and Seinfeld is 48, a 17-year-difference that is therefore less amazing than that Shoshanna Lonstein’s life could last so long that she could meet Jerry when she was 18 and he was 39, but there you go.

“Comedian” was filmed over the course of a year by director Christian Charles and producer Gary Streiner, who used two “store-bought” video cameras and followed Seinfeld around. If that is all they did for a year, then this was a waste of their time, since the footage, however interesting, is the backstage variety that could easily be obtained in a week. There are no deep revelations, no shocking moments of truth, and many, many conversations in which Seinfeld and other comics discuss their acts with discouragement and despair. The movie was produced by Seinfeld, and protects him. The visuals tend toward the dim, the gray and the washed-out, and you wish instead of spending a year with their store-boughts, they’d spent a month and used the leftover to hire a cinematographer.

Why, you might wonder, would a man with untold millions in the bank go on a tour of comedy clubs? What’s in it for him if the people in Cleveland laugh? Why, for that matter, does Jay Leno go to comedy clubs every single week, even after having been called over by Johnny for the ultimate reward? Is it because to walk out on the stage, to risk all, to depend on your nerve and skill, and to possibly “die,” is an addiction? Gamblers, they say, don’t want to win so much as they want to play. They like the action. They tend to keep gambling until they have lost all their money. There may be a connection between the two obsessions, although gamblers at least say they are having fun, and stand-up comics, judging by this film, are miserable, self-tortured beings, to whom success represents only a higher place to fall from.