It is an ancient Japanese tradition to pay homage to one’s ancestors. It is a modern Japanese tradition to fly to Hawaii for golf. The hero of “Cold Fever,” a Tokyo businessman named Atsushi, is preparing for a golf holiday in the islands when he is shamed by a relative into changing his plans. Instead, he will fly to Iceland, where his parents were drowned in a river some years before.

So begins an odd and beautiful film about a pilgrimage to a desolate land, gripped by winter and inhabited by people whose customs are a mystery not only to the visitor from Japan, but to us. Early in the film, Atsushi (Masatoshi Nagase) is in an airport cab that stops so the driver can visit an isolated farmhouse. The visitor waits in the cab as long as he can bear it, and then peeks inside, where a roomful of Icelanders are performing a ritual with sheep and weird musical instruments. What are they doing? We do not have the slightest idea.

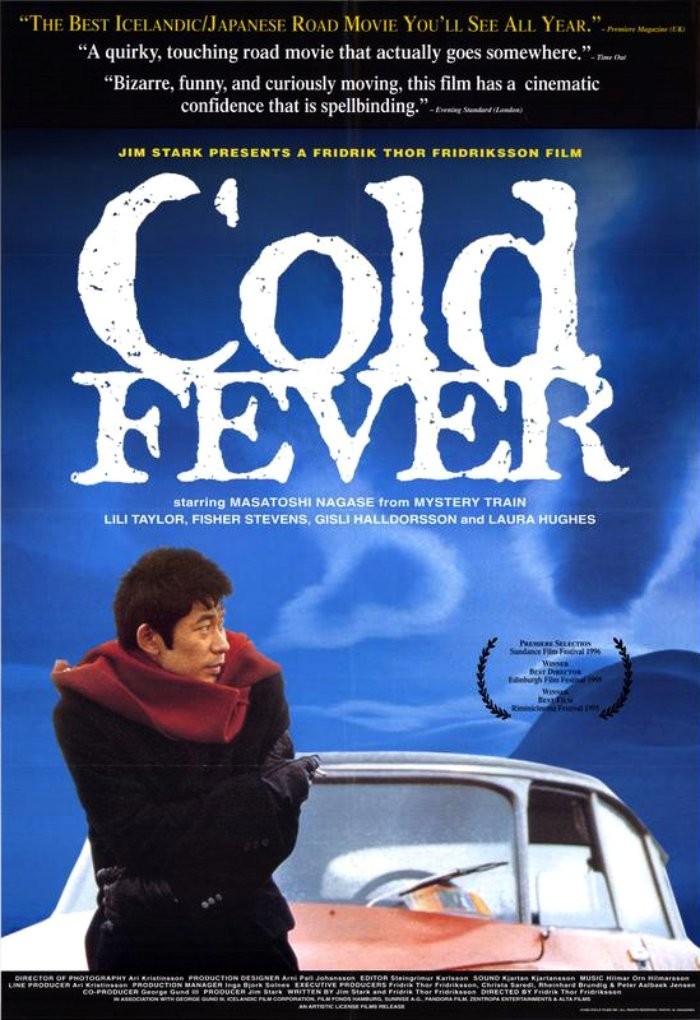

Atsushi presses on. He is ill-prepared for a journey in this frigid land, where the sun is a brief finger drawn between the dawn and the dusk. He comes into the possession of a dubious car, an exhausted Citroen, and sets off down roads with alarming signs asking, “Does anyone know you are going this way?” Why his parents chose this landscape as a holiday destination is a question not answered.

But the film finds humor and beauty in its odyssey. It takes the classic form of the road movie and populates it with improbable wanderers in the snow. A woman, for example, who “collects funerals,” and photographs them all over the world. An American couple (Lili Taylor and Fisher Stevens) who hitchhike with him, and continue the quarrel their marriage seems to be based on. And an Icelander who repairs cars by singing at them.

The Icelanders sing a lot in this movie, maybe to keep their spirits up, maybe to keep warm. One scene involves a group of barflies who sing American country and western songs and drink the “national beverage,” which they helpfully explain is called “Black Death,” while consuming steaming platters of sheep testicles.

Walking into this movie, my knowledge of Iceland was largely limited to (1) it is one of the five Nordic nations, (2) trans-Atlantic flights refueled there in the years before jets, and (3) Bobby Fischer won the World Chess Championship there. What the movie achieves, almost as a side effect, is to portray Iceland as a haunting and beautiful land, where the snow in the moonlight creates such an ethereal landscape that when the spirit of a child appears to guide Atsushi we are almost not surprised. I can now imagine visiting Iceland–not that it’s at the top of my list.

The actor Masatoshi Nagase is an old hand at movies about strangers in strange lands. He was the star of Jim Jarmusch’s “Mystery Train” (1989), playing a Japanese tourist in search of Memphis rock ‘n’ roll shrines. The connection is not a coincidence; “Cold Fever” was produced by Jim Stark, who produced the Jarmusch film. So you could describe this movie as a retread (“Where will we send Nagase this time?”), except that it earns its right to stand alone by taking an ancient formula and rebuilding it with scenes that feel absolutely new. (The director, Fridrik Thor Fridriksson, made “Children of Nature,” which was nominated in the Oscar foreign-film category in 1991.) I run into people who ask me what new movies they should see. When I describe a movie like this, they roll their eyes. A Japanese businessman? In Iceland? Yeah, I say, so why don’t you go see a movie made out of special effects and explosions? That’ll be real new for you. But not as new as a shot in “Cold Fever” where the wind whips across a moonlit landscape, and lifts a sheet of snow, which falls back with a sigh.