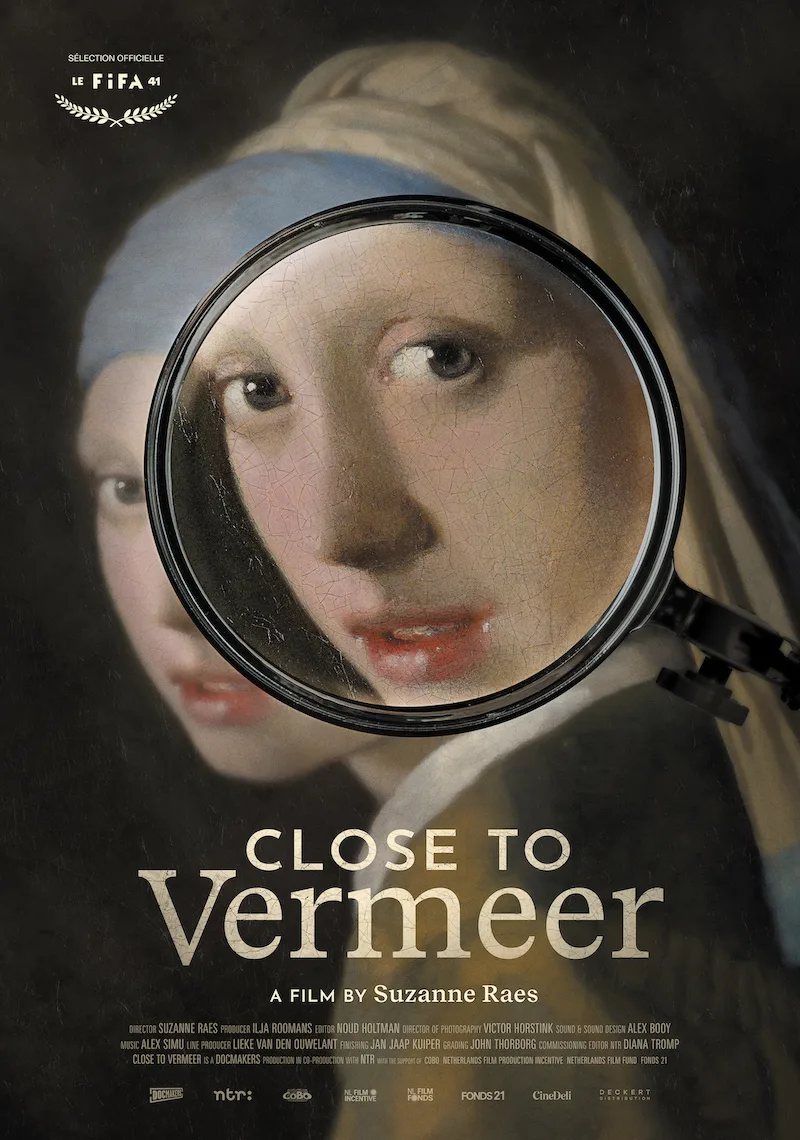

There’s a moment in Suzanne Raes’s “Close to Vermeer,” a documentary about the curation of a Vermeer exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, where Abbie Vandivere, a conservator and researcher at the Mauritshuis Museum in The Netherlands, describes the first time she held Vermeer’s The Girl with the Pearl Earring in her hands. Her exhilaration and awe is palpable. Even the memory makes her eyes shine. To actually hold the physical object! “Close to Vermeer” is a gentle, thoughtful documentary, populated by knowledgeable individuals like Vandivere, experts at the top of their fields who have maintained their passion and love for the subject.

The documentary covers a lot of ground. It shows the challenges of curating a show of this magnitude (Vermeer’s very small body of work—just 34 paintings—is scattered over the globe). It also extensively gets into the various controversies surrounding “authorship,” particularly with a couple of contested paintings. Both sides make their case as to why this or that work is or is not a Vermeer. These controversies sometimes make international headlines, quite a development for a painter who spent the two centuries after his death in almost total obscurity.

The main figure in “Close to Vermeer,” besides the artist himself, is George Weber, curator of the Vermeer exhibition, feeling the pressure to add new scholarship to accompany the show. It’s not enough to just put the paintings on the walls. He wants to deepen understanding, and he also wants to maybe settle the debate on the contested Vermeers once and for all.

Weber describes the first moment he ever saw a Vermeer as a teenager: “I actually fainted.” Weber is a very controlled and elegant man, but emotion keeps coming up in him. He feels passionately about the subject. His comments are sprinkled with gems like: “[Vermeer] seems to know that warm yellow light has cold blue shadows.” A comment like this helps me to see what he sees. The film is filled with almost microscopic shots of Vermeer’s work, the tiny cracks in the paint, the shadowy brush strokes, zooming in on the details. Pieter Roelofs, Weber’s co-curator, travels to museums worldwide to negotiate lending out “their” Vermeers for the exhibition. It’s a fascinating inside glimpse of backroom dealings at a very high level.

Along with these practical concerns, there are “guides” who help place Johannes Vermeer in a larger context. People like Abbie Vandivere and Jonathan Janson, a painter and Vermeer expert. He is the one who points out the creases in the yellow shawl of one of the contested paintings. He thinks they look crude, not as detailed as they should be. He has opinions. Weber visits him to discuss these issues. They spend time discussing colors, shadows, brush strokes, and the mysteries still surrounding Vermeer, his time, his life, and his work.

We know a lot more about Rembrandt, Vermeer’s contemporary, than we do about Vermeer. Rembrandt was prolific and versatile; his work was clearly influenced by Italian masters—all those huge shadowy portraits—and he almost obsessively put himself into paintings, the Dutch Golden Age verge of a selfie. Rembrandt experienced much success in his life.

Vermeer, on the other hand, had modest success and was not prolific at all. His paintings are all quite small in size and feature the same rooms, exquisitely rendered in tiny detail. In each, you see the same light sources, the same utensils, and maybe even the same people. He clearly painted people he knew intimately, and his primary subjects were women. There is no distance in approach from his subjects, no idealization or overt flattery. They are seen in homey settings, making lace, playing the virginal, sipping wine offered by a suitor. These are not “court” paintings. The experts here are all very good teachers.

There’s something soothing about “Close to Vermeer.” I’m the daughter of a rare book collector, a man who spent his free time tracking down books (mostly by Irish authors, primarily Francis Stuart). He’d show us the copyright page of his latest acquisition, and explain why it was relevant. He’d tell us stories about the publication, he’d gently turn the pages, treating the book with respect. This was the air I breathed as a child. And so there’s something soothing about listening to people sharing their knowledge, helping us understand why something is rare or special, unique or valuable.

In a world of “hot takes” and uninformed “takedowns,” where expertise is increasingly de-valued across the board, the experts in “Close to Vermeer” are a comforting bunch. They know a lot, they share what they know, and they help us to not just look at a Vermeer, but to see.

Now playing in theaters.