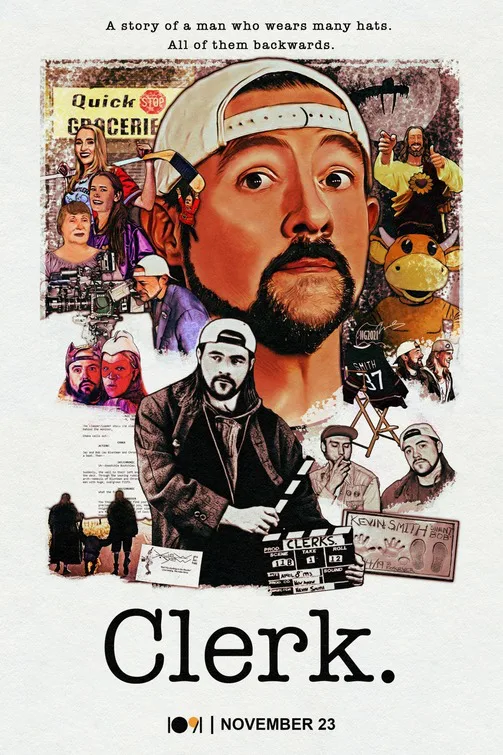

At the very end of the unfortunate biographical doc “Clerk,” self-exiled slacker king and New Jersey-based filmmaker Kevin Smith paraphrases Bruce Springsteen’s “The Wish.” In that song, The Boss sings: “And if it’s a funny old world, ma, where a little boy’s wishes come true/well, I got a few in my pocket and a special one just for you.” In this documentary, Silent Bob tears up when he says his creative successes are a “a little boy’s wish coming true over and over and over again. “It shouldn’t have happened,” Smith persists, “and it f**ing did, and, like, cracked open the f**ing universe.”

There’s a lot to unpack there, especially given that most of “Clerk” uses footage from Smith’s films and interviews with Smith’s mother Grace—and his brother Donald, his daughter Harley Quinn, his wife Jennifer, and his many collaborators—to confirm something that his fans, the movie’s ideal (and probably only) audience, already feel: the world is a better place for having Kevin Smith in it. Probably, but you won’t believe that based on the evidence presented in “Clerk.”

“Clerk” mostly follows Smith’s career as a filmmaker, though it also continues long enough to shout-out his spoken word/stand-up comedy performances, his podcasts, his movie merchandise, and his IMDb talk show. Everything after Smith’s movies, which even he admits are technically rough sledding, serves to confirm Smith’s self-image as a very lucky guy who’s now all about using his art to be himself, whatever that means.

Smith and his pals guardedly (or maybe half-heartedly) suggest that he’s already wrestled with and maybe even outgrown the expectations that were foisted upon him by the critical “intelligentsia” that boosted “Clerks,” his 1994 breakthrough indie comedy. Author and Smith champion John Pierson dismisses bad reviews of “Mallrats,” Smith’s pandering, loosey-goosey follow-up to “Clerks,” for being written by “critics who made him” who were “feeling betrayed.” That’s also probably true, but what about everyone else who didn’t and probably still don’t care that much about Smith and his chummy cult of personality?

Smith’s famous ‘splainin’ hands work over time as he struggles to articulate why his creative successes, like “Clerks” and “Chasing Amy,” mean as much to him as his box office duds, like “Jersey Girl” and “Zack and Miri Make a Porno.” Each project informs the next and also expands Smith’s understanding of what works and what doesn’t, though it’s often hard to tell why that matters beyond dutiful, self-serving interviews with his grateful friends and colleagues.

Ben Affleck and Joey Lauren Adams thank Smith in “Clerk” for giving them creative autonomy and opportunity on “Chasing Amy.” But these visually interchangeable testimonials aren’t as endearing as scenes where Smith lavishes praise on his regular co-star and on-screen wingman Jason Mewes, who blushes and marvels silently when Smith insists that he out-shone “professional comedians” in “Dogma,” Smith’s endearingly childish 1999 apocalypse comedy.

Unfortunately, most of the talking head interviews in “Clerk” only confirm Smith’s high self-regard. There’s some truth to grandiose claims made by guys like former Marvel Comics editor-in-chief and ex-Daredevil co-writer Joe Quesada, who says that Smith not only “saved my career, but contributed to the saving of comics.” But even if you had enough time to check Quesada’s mental math (and adjust for considerable inflation): who cares about this stuff beyond the uninitiated? Who but Smith’s fans will want to see the late comics figurehead Stan Lee trade compliments with Smith, let alone nod along with magician Penn Jillette when he praises Smith for being “important to the culture.” Which culture and important how?

Smith’s halting commentary is often the most frustrating thing of “Clerk” given how emotionally charged, but essentially non-introspective he tends to be. He claims to have been unaware of former patron Harvey Weinstein’s sexual misconduct, and quickly mentions his already well-publicized dedication of all post-#MeToo Miramax royalties to female filmmakers. A documentary that expanded on that (or kept after Smith more often) could have been interesting, but “Clerk” often remains within Smith’s slip of a comfort zone. So instead of self-criticism or just plain self-assessment, we mostly get a lot of self-regard and self-pity, like when Smith shrugs that “Jersey Girl” bombed because it was different than his previous films (“How do you sell that?”).

Watching Smith’s buddies pay him heartfelt tribute is one thing, but that doesn’t make spending so much time (115 minutes???) with his fawning co-conspirators feel much less oppressive. Again, there’s something to testimonials from guys like “Fatman on Batman” podcast co-host Marc Bernardin, who hails Smith for pushing his predominantly white fanbase to make room for Marc Bernard, an African-American comics fan. But everything in “Clerk” eventually leads back to Smith, who only explains so much about Smith’s cracked universe, no matter how forcefully or frequently it erupts.

Now available on digital platforms.