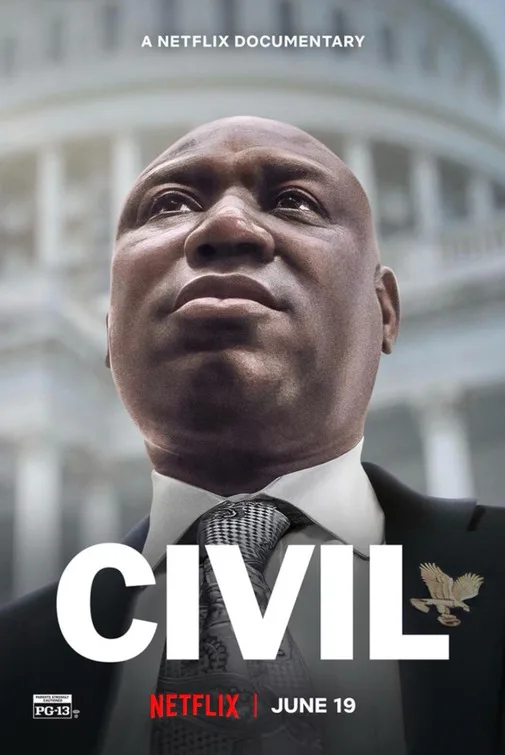

At the beginning of “CIVIL,” Nadia Hallgren’s Netflix documentary in limited theatrical today and streaming on Juneteenth, civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump tells us his law firm gets about 500 calls a day. “People seek me out because they want a Black lawyer,” he says. “Someone who understands their life experiences. Someone they feel they can trust.” Crump is on the phone a lot here, talking to potential clients, his law partners, his wife and daughter and his Mom. One of his nicknames is “the Black Attorney General” based on the number of cases he accepts. There are the high-profile cases that the public knows, as well as low-profile cases that don’t make the news cycle. Hallgren covers “a fraction” of these cases during the time period of 2020-2021 when Crump had his biggest and most successful civil lawsuit, a $27 million win for the family of George Floyd.

“CIVIL” opens with Crump in silhouette, taking the call for his services from a relative of Floyd. It ends with his reaction to the guilty verdicts in criminal case against Derek Chauvin, the former Minneapolis police officer who murdered Floyd by kneeling on his neck for over nine minutes. Between these two scenes, Hallgren shows a series of civil cases Crump is currently working on, as well as the past cases that made him so well known. Previous clients include the families of Breonna Taylor, Mike Brown, and Trayvon Martin. All of these deceased Black people have something in common. It is truly disquieting that Crump keeps showing up on TV to represent case after similar case; he’s a ubiquitous fixture in a flawed justice system. However, shooting cases only take up 5-10% of his law firm’s case load.

“Before Trayvon Martin, nobody cared about Black people getting shot,” says Crump as he acknowledges the mistakes he made in that case: “Trayvon prepared me for George Floyd.” Though “CIVIL” documents, among other things, a case of banking while Black and another suit brought by farmers against Monsanto, it’s Floyd’s case that haunts the film. Thankfully, Hallgren avoids showing any footage of his last moments, opting instead to show scenes from the worldwide movement his death inspired. There are also clips of a Fox News anchor calling Crump “the most dangerous man in America” and blaming him for racism.

Several times, Crump clarifies that he’s a civil attorney, not a criminal one, and therefore cannot prosecute anyone for breaking the law. Instead, he feels a financial settlement may be the only justice his clients will get. He has 25 years of experience working in this vein. “CIVIL” shows commercials from Crump’s early days as a personal injury lawyer or “rent lawyer” as he called his position. “We took whatever case that would pay the rent,” he tells us. When pressed about criticism (some of it from Black people) that a focus on monetary compensation is shallow and distasteful, Crump is unapologetic. While I understood his explanation that people should be held accountable, his comment that “$1-3 million is the going rate for Black life” shook me to my pessimistic, cynical core.

What shook me even more was the consistently exhausted look on Benjamin Crump’s face, caused by the repetition of case after case. It’s a Groundhog’s Day of the same injustices, alleviated only by the constant support of his close-knit family. His mother is a constant voice on the other end of his phone, as are his wife and daughter. They are incredibly helpful, offering support and occasionally ribbing their famous relative to lighten the mood. Though he expresses some optimism, Hallgren’s camera keeps catching its subject in deep thought while making that face and sighing. And though “CIVIL” is a well done, if standard documentary, I found it difficult to watch at times. I felt that same exhaustion, almost to the point of being overwhelmed.

As a process-loving person, I wanted more scenes of case work. We briefly see a mock trial where Crump hones his arguments, and a few scenes of him advising what to say in press conferences. Each client is interesting enough to warrant more screen time. We also see him in action at those press conferences, at times barely containing his own anger at the system. At his side is his charismatic bodyguard, a former gang member named Silky Slim who’s quite knowledgeable about his job. That a civil rights attorney needs protection from constant death threats is far too easy to believe nowadays. “It might not be a camera next time,” says Slim about the press conferences. “It might be a gun.”

“CIVIL” won’t change any minds about its subject, but it does a good job of delivering “fly on the wall” observations of the year it covers. No matter what one thinks of him, Benjamin Crump gets results. His victories are ultimately Pyrrhic ones; no amount of money can bring back those who were lost, nor can it replicate what might have been achieved had they lived.

On Netflix Sunday, June 19th.