It is not agreed how “Chopper” Read got his nickname. Some say it was because he chopped off the toes of his enemies. Others believe it was because he had his own ears chopped off, or because he had his teeth capped in metal. He is Australia’s most infamous prisoner, a best-selling author, a vicious killer, a seething mass of contradictions. “Chopper” tells his story with a kind of fascinated horror.

Is everyone in Australia a few degrees off from true north? You can search in vain through the national cinema for characters who are ordinary or even boring; everyone is more colorful than life. If England is a nation of eccentrics, Australia leaves it at the starting line. Chopper Read is the latest in a distinguished line that includes Ned Kelly, Mad Max, and Russell Crowe’s Hando in “Romper Stomper.” The fact that Chopper is real only underlines the point.

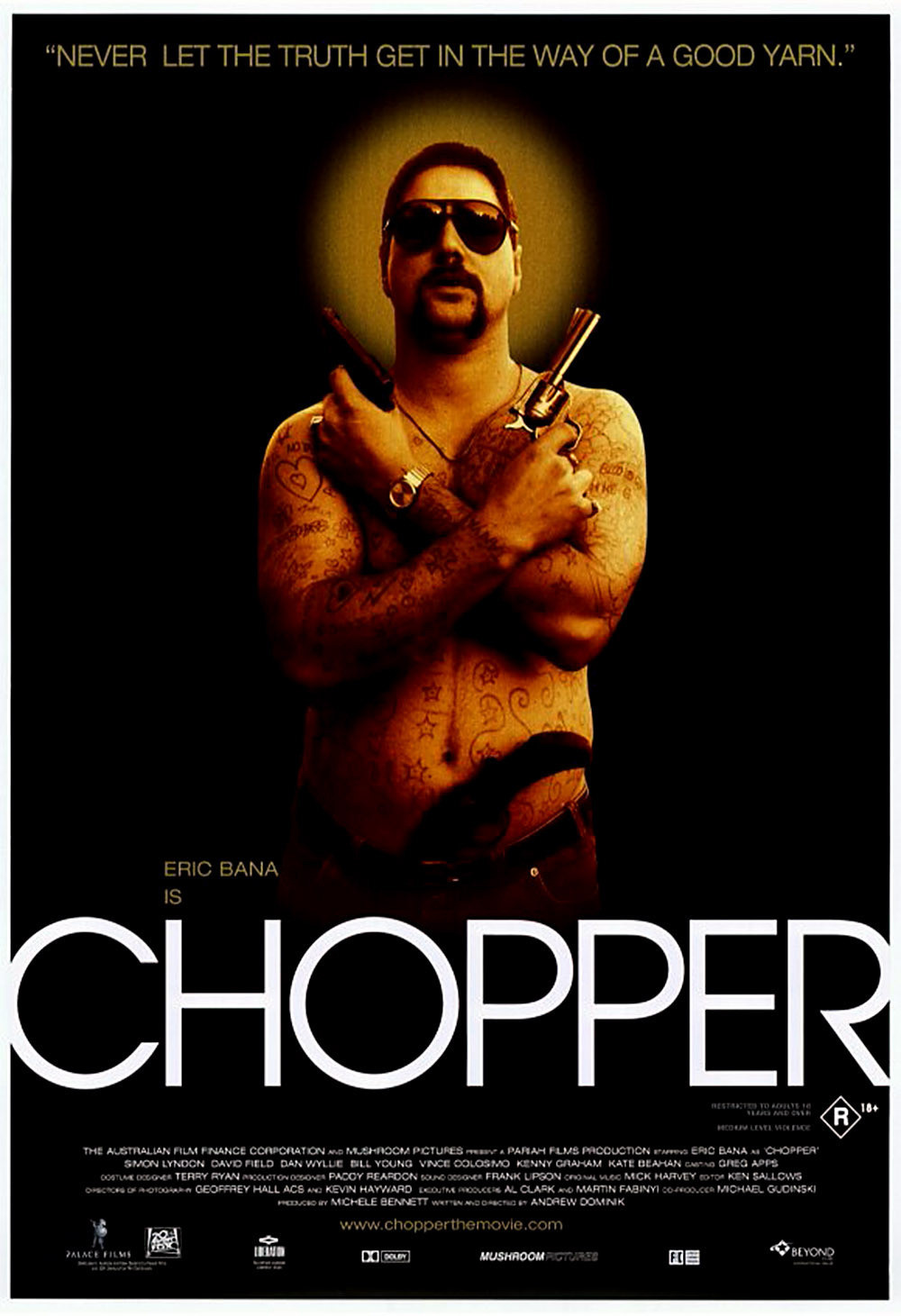

Since the real Chopper is again behind bars, the film depends entirely on its casting, and in a comedian named Eric Bana the filmmakers have found, I think, a future star. He creates a character so fearsome and yet so clueless and wounded that we can’t tell if the movie comes to praise or bury him. There is a scene in the movie where Chopper is stabbed by his best friend, and keeps right on talking as if nothing has happened; his nonchalance is terrifying. And another where he shoots a drug dealer and then thoughtfully drives him to the emergency room. Bana’s performance makes the character believable–in fact, unforgettable. We feel we’re looking at a hard man, not at an actor playing one.

As the film opens, Chopper is in prison watching himself on television. He seems curiously conflicted about what he sees–as if the Chopper on TV has been somehow constructed by others and then installed inside his skin. The writer-director Andrew Dominik and producer Michele Bennett, who met Chopper Read while preparing the film, sensed the same thing. “After we’d passed some time with him,” says Bennett, “we could see that he was waiting to gauge our reaction before he proceeded. We did offer to show him the script, but he declined, remarking, `Anything I say would be fiddling. I want to know what you think of me,’ so we didn’t pursue it. He pretends that he doesn’t care how he’s perceived by others, but I suspect he really does.” That’s how he comes across as a film–as a man who seems to stand outside himself and watch what Chopper does. He’s as fascinated by himself as we are, and isolated from his actions. Even pain doesn’t seem to penetrate. He looks down at blood pouring from his body as if someone else has been wounded, and then up at his attacker as if expressing regret that it should have come to this.

The movie wisely declines to offer a psychological explanation for Chopper’s violent amorality. But it provides a clue in the way he stands outside criminal gangs and has no associates; he is not a “criminal,” if that word implies a profession, but a violent psychopath who is seized by sudden rages. There is a startling moment in the film, during a brief stretch on the streets between prison sentences, when he revisits old haunts and old friends and seems genial and conciliatory–until his mad-dog side leaps out in uncontrolled fury. The earlier niceness was not an act to throw people off their guard, we sense; he really was feeling friendly, and did not necessarily anticipate the sudden rush of rage.

Eric Bana’s performance suggests he will soon be leaving the comedy clubs of Australia and turning up as a Bond villain or a madman in a special-effects picture. He has a quality no acting school can teach and few actors can match: You cannot look away from him. The performance is so . . . strange. The parts you remember best are the times when he seems disappointed in others, or in himself, as if filled with sadness that the world must contain so much pain caused to or by him. Of course in creating this Chopper he may simply be going along with the original Chopper’s act, and the real Chopper Read with his TV interviews and best sellers may be a performance, too. Whatever the reality, Chopper is a real piece of work, and so is Bana.

Note: Chopper Read speaks in an unalloyed Australian accent that may be difficult for some North American audiences; he’s no toned-down mid-Pacific Crocodile Dundee. I understood most of what he was saying. And when you don’t catch the words, you get the drift.