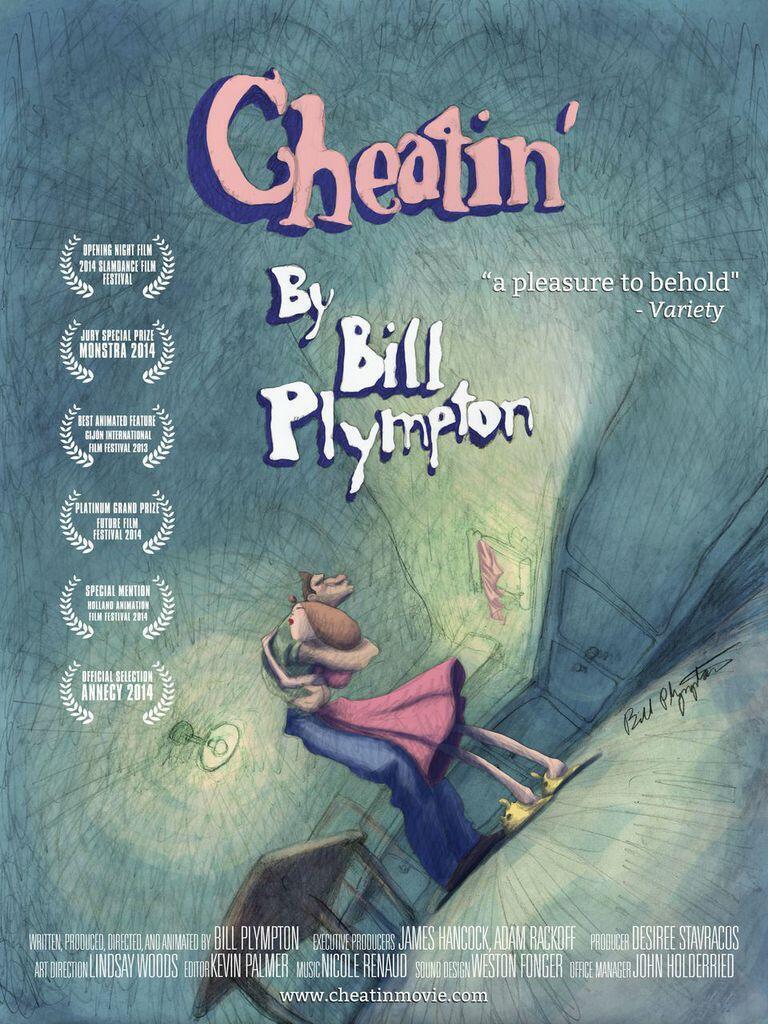

You don’t need to pay attention to the story in “Cheatin’,” a feature-length cartoon and adult fairy tale with no serious moral. “Cheatin'” was created and drawn by Bill Plympton, a sensualist, and unabashed lover of muscular, grotesque images. Plympton’s also a master fantasist, and a genius when it comes to surreal sight gags, crude sexual humor, and almost every other kind of slapstick-y, physical humor. His hand-drawn animation style is impressionistic, a garish combination of water colors and pencils. And his characters—in this case, a newly-married couple whose relationship rapidly unravels when she becomes convinced that he’s sleeping around—can never be confused for realistic: at any given moment, human bodies might stretch, or balloon until they’re as big as characters’ boisterous feelings. So while “Cheatin'”‘s ending is a little too manic for its own good, it really doesn’t matter whether Plympton’s latest yarn turns out to be a tall tale with a happy ending, or a shaggy dog joke with no ending at all.

In that sense, “Cheatin'” is essentially an ever-transforming, narrative-light nightmare that Ella and her dream lover can’t wake from. In the film’s introductory scenes, Ella gets inexplicably picked on by a carnival barker. She stands her ground, and rejects a ticket of admission that he patronizingly hands her. She then spends the bulk of the film stuck in a fantasy that she refuses to admit is a fantasy, wooing a lunk-headed muscle-man who’s too dumb to understand when other women are flirting with him.

Ella’s fantasies are most exciting when she’s least in control of herself. Scenes like the one where Jake tries to jump-start his lawn-mower while a nosy neighbor tries to catch his eye are priceless. Ella furtively watches from her house’s backdoor while Jake mechanically yanks on his mower’s cord. A handkerchief wafts over. Jake returns it, and goes back to yanking. Then a brassiere lands at his feet. Jake returns it, and keeps right on pulling. Then a veritable fleet of linen sails over Jake’s head, reminding us that we’re in a world motivated by feelings, not sensible logic.

Nothing in Plympton’s film can be dismissed as “just a dream,” because everything in the film is dream-like. Indeed, Ella and Jake are most powerless whenever they try to assert control over their lives through sex, daily chores, or, uh, body-swapping (this isn’t really a spoiler since it doesn’t make any more sense in context). “Cheatin'” is therefore least interesting when it’s most rigidly bound by a narrative. Ella and Jake are especially compelling whenever they behave like lumpy shapes that excite, flit about, and then never stop erupting around each other.

So while “Cheatin'” does have a narrative spine, it’s most entertaining when it’s hardest to pin down. You can easily get lost in Plympton’s brash animation style since his line-work is simultaneously loose, and decisive. And his sense of humor is infectious because it’s well-timed, and proudly freaky, especially during any scene where Jake is ogled by hungry, lip-teasing bachelorettes. The film’s singular images stay with you because they’re realized with uncommon clarity and boundless energy. “Cheatin'” is a highlight of Plympton’s robust body of work because motion—not the journey, or the destination—is always its creator’s priority.