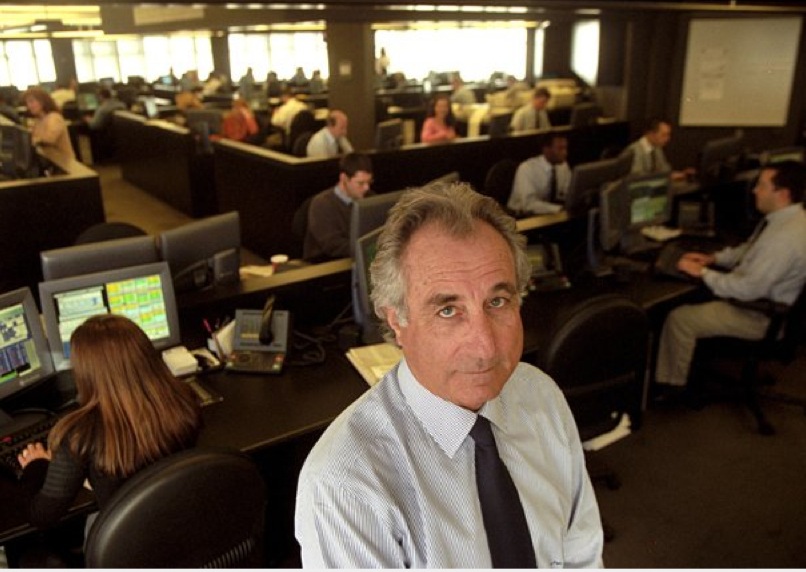

Through the best of times, through the worst of times, year after year, Bernie Madoff’s return on investment remained the same. The line on the graph climbed at a steady 25 degrees. It never faltered — until, like Wile E. Coyote, it ran off the edge of a cliff and continued running in thin air. Then came the collapse of a $50 billion Ponzi scheme, the largest in history.

No one could believe it. In theory, it was impossible. Market professionals knew in their guts his returns were impossible. And they all knew about Bernie. No matter where you went in the world of hedge funds, no matter who you spoke to, Bernie was the man everyone knew. They would be asked, “What do you know about Bernie?” They would reply, “What do YOU know about Bernie?” What they all knew was that nobody, but nobody, could get returns like that.

“Chasing Madoff” tells the story of a man named Harry Markopolos, who gathered the facts and figures about Madoff 10 years before anyone else did. He had the charts. He had the graphs. It was as obvious as the day was long that Madoff was running a Ponzi scheme. How a Ponzi works: You never buy anything. You simply pay your current investors out of money from new investors. For this to work, you always need new money. For years, Madoff had it.

“It can’t be a Ponzi,” his investors told each other, “because his fund is closed to new investment!” Yes, but they were able to buy in because they “knew somebody.” Madoff’s investors were rich people, other hedge funds, banks, trusts. You’d think people like that would know (a) there is no free lunch, and (b) you never put all your eggs in one basket. Remarkable numbers of them lost their total investment, however. In enclaves of millionaires, whole families were wiped out.

They were blinded by greed. They knew the numbers were impossible. But since Madoff stayed in business year after year, they might have told themselves: It can’t last, but I’m willing to clean up on other people’s losses. Then there were the professional managers who bought into Madoff’s funds for competitive reasons. For them, it was a way to raise the rate of return on their investments. Many rich people had no idea they were invested in Madoff via “feeder funds.” The function of such funds was to provide outside capital to keep the Ponzi afloat.

But what about the Securities and Exchange Commission? What about the Wall Street Journal? What about the New York Times? Bloomberg News? Didn’t they know? Harry Markopolos told them. He was a respected professional. Year after year, he supplied them all with carefully documented evidence of what the scheme was and how it worked. The problem was, they didn’t want to know. Its scope was so vast, Madoff’s webs were so complex, that if it were true, that would make it the largest Ponzi scheme in history. Which it was.

“Chasing Madoff” is not a very good documentary, but it’s a very devastating one. It consists of this entire story told by Markopolos and his fellow Madoff-chasers Frank Casey and Neil Chelo. There’s footage from congressional investigations. SEC staff members are called on the carpet. No one from the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal is asked to explain their inaction. We do hear from individual investors who lost their life savings — but not from any traders or firms that bought into Madoff. Nor do we hear from Madoff himself. We get many portentous shots of skylines, Wall Street, the SEC headquarters, Madoff’s yacht and cable news reports.

There’s precious little, indeed, that we find out here but didn’t already know from the news coverage at the time. The only smoking gun is that Madoff’s guilt was exposed clearly and repeatedly by Markopolos in the decade before his fall. Not only did the system fail, but it failed because of the willful ignorance of those with the responsibility to make it work.

What do we learn at the end of it all? There is no free lunch. Never put all your eggs in one basket. One of the many people who forgot those helpful rules was Bernie Madoff.