Political movies often play cute in drawing parallels with actual figures. They drop broad hints that a character is “really” Dick Cheney or Bill Clinton and so on. “Casino Jack” is so forthright, it is stunning. The film is “inspired by real events,” and the characters in this film have the names of the people in those real events: Jack Abramoff, Michael Scanlon, Rep. Tom DeLay, Ralph Reed, Karl Rove, George W. Bush, Rep. Bob Ney and Sen. John McCain.

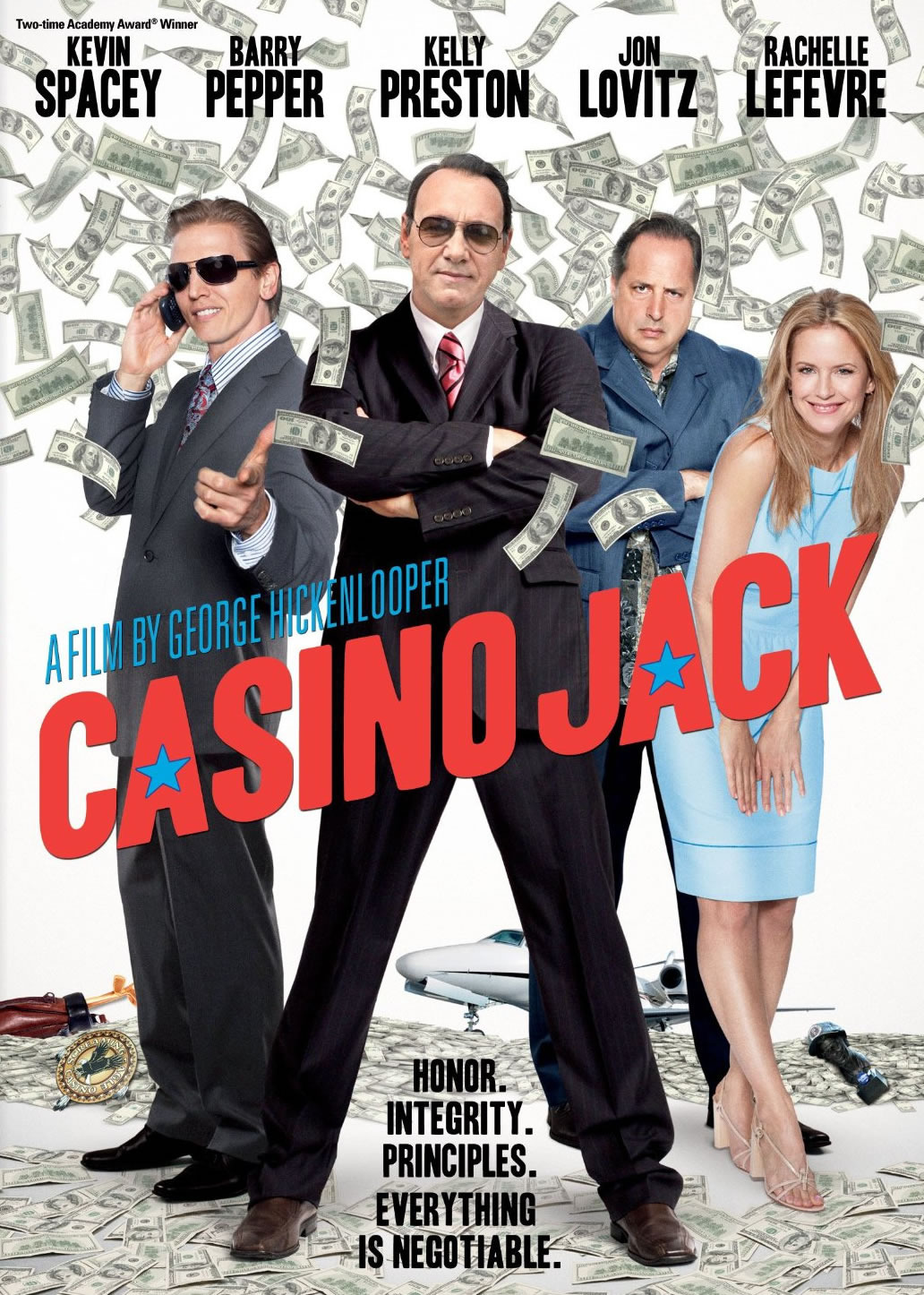

This decision to name names by the director George Hickenlooper seems based on boldness, recklessness or perhaps iron-clad legal assurances. His film uses a fictional sledgehammer to attack the cozy love triangle involving lobbyists, lawmakers and money. It stars Kevin Spacey in an exact and not entirely unsympathetic performance as Abramoff, once one of the most powerful lobbyists in Washington, who was convicted on charges involving the funds he stole from wealthy Indian casinos while arranging laws for their convenience on Capitol Hill. He has been released on parole and just finished a stint working in a Baltimore pizza parlor.

The first press screening of the film at the Toronto International Film Festival was witnessed in a sort of stunned silence by a capacity audience, interrupted slightly by an undercurrent of incredulous murmurs and soft laughter when Spacey, as Abramoff, in a fantasy sequence, explodes at a Senate hearing chaired by McCain. Having evoked the Fifth Amendment repeatedly, he’s unable to restrain himself any longer and jumps to his feet to accuse the very members of the Senate panel of having taken campaign contributions and favors from his Indian clients and then voting in their favor. Abramoff shows some degree of honor among thieves by not pulling such a stunt.

Astonishingly, Hickenlooper intercuts real footage of the real hearing and the real John McCain with Spacey’s performance. Can he get away with this? I guess so. The film’s distributor, ATO Pictures, has no doubt had the film scrutinized by its attorneys. Apart from that, there’s the likelihood (which lawyers may think but cannot say) that no one named in this film is very likely to sue. The Abramoff scandal was called at the time the biggest since Watergate (both were broken by the Washington Post), but in the years since his sentencing in 2006, his name has faded from everyday reference, and it’s doubtful anyone desires to make it current again. With Alex Gibney’s doc “Casino Jack and the United States of Money” also around, those deep waters are being sufficiently stirred.

The film’s story line can be briefly summarized: The lobbyist Abramoff was a dutiful family man and Republican standard bearer who defrauded Indian tribes out of millions to lobby for their casinos. That enriched him and partner Michael Scanlon (Barry Pepper) and a good many members of Congress, not all of them Republicans. Abramoff worked out every day, was an observant member of his temple and a smooth and elegant dresser. Somehow at his core, he had no principles and no honesty.

If Casino Jack puts up a good front, George Hickenlooper’s film is merciless with Scanlon, a venal and vulgar man with the effrontery to flaunt his corruption. It is Spacey’s performance that contains most of the movie’s mystery; although Abramoff’s actions left little room for justification, in Spacey’s performance, there is some. Abramoff used much of the stolen money for good works, which made him appear charitable. His principal charity was himself, but there you are.

There are scenes here that make you wonder why the Abramoff scandals (plural) didn’t outshine Watergate as the day does the night. Within Abramoff there is some small instinct for simple justice, and the film’s most dramatic scene comes as he snaps at that hearing, ignores his lawyer, forgets the Fifth Amendment and tells the panel members to their faces that they were happy to take his cash.

The overall message of “Casino Jack” has become familiar. Corporate and industry lobbyists are the real rulers in Washington, and their dollars are the real votes. Both parties harbor corruption, with the Republicans grabbing the breasts and thighs, and the Democrats pleased to have the drumsticks and wings. Jack Abramoff didn’t invent this system. He simply gamed it until Scanlon’s boldness betrayed them and another generation of lobbyists took over. Have you heard the banks are broke again?

Footnote: George Hickenlooper, the film’s director, died on Oct. 29. I met him in 1991, when he interviewed me for a book. The same year, he released his documentary “Hearts of Darkness,” about Francis Ford Coppola and the making of “Apocalypse Now.” It remains one of the best records ever made about the making of a film.

Parts of this review were contained in my report from Toronto.