42 Carmine Street is the humble storefront home—blink and you’ll miss it—of Carmine Street Guitars, established by Rick Kelly in the 1970s, and in its current West Village location since 1990. If you didn’t know better, you’d think it was a mom-and-pop hardware store, instead of a pilgrimage destination for the greatest guitar players in the world. There’s a workshop in the back where Kelly builds custom guitars, using wood salvaged from all over New York City.

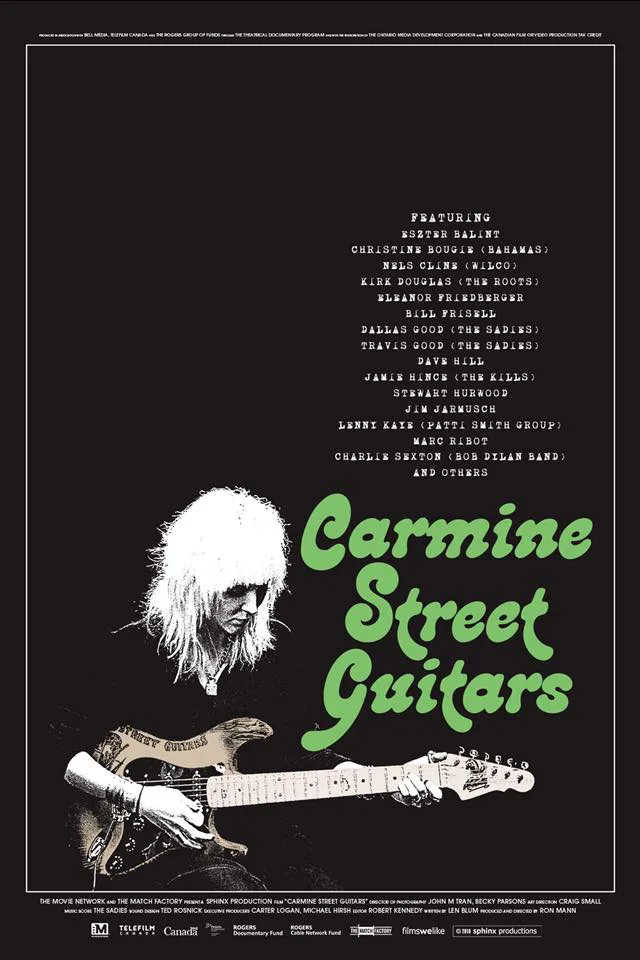

Ron Mann’s new documentary, “Carmine Street Guitars,” is a “week in the life” of the store, with a parade of famous legends “stopping by” to chat, play guitars, talk with Kelly about music, about his process. The setup is somewhat contrived, and there’s a stilted quality to some of the conversations, clearly urged on by off-camera prompts that we don’t hear. But “Carmine Street Guitars” has its intense pleasures too, and those come mainly from being in the presence of such a devoted craftsman, and watching how he works. The rhythm is slow. You really get the sense that when you walk through the doors of Carmine Street Guitars, you step outside of time.

Carmine Street Guitars has just three employees: Kelly, his mother Dorothy who answers the phones and does the books, and Cindy Hulej, Kelly’s young apprentice, who burns beautiful custom designs into the guitars built by Kelly. In the workshop in the back of the store, Kelly and Hulej sit at opposite tables, silently consumed in carving, shellacking, burning. Quiet absorption is probably the norm for these two. “Talking heads” are a cliche in documentaries, but a little outside perspective might have helped “Carmine Street Guitars,” since Kelly and Hulej are too busy working to explain their processes.

One by one, legends show up, to try out guitars. These sequences have their awkward moments, where you can feel the self-conscious “set up” of it all, but the subject is so interesting, and the music played by these people is so gorgeous, it’s forgivable. There are many gems dropped along the way. Kelly talks with Patti Smith’s guitarist Lenny Kaye about coming to New York when he was a teenager to see Jimi Hendrix play, before Jimi was even “Jimi Hendrix,” and Kelly and Bill Frisell have a fascinating conversation about Leo Fender (one of Kelly’s inspirations.) Each guest who visits plays a song on a Kelly-made guitar, and in these beautiful meditative sequences time stands still. There’s almost an exhale in such moments, where nothing is required of you but relax and enjoy the music. Kirk Douglas from The Roots asks Kelly about the different tools he uses, and Kelly shows off some of them, a small tutorial (the film could have used more of this. Kelly’s process is mostly shown, but not explained). Jim Jarmusch shows up with a guitar for repair, and he and Kelly have a long conversation about catalpa wood, ash trees, redwood trees. These people know their wood! There’s a beautiful shot of all of the guitars Kelly made for Lou Reed, lying on the floor, back to back, beautiful historic instruments.

One of the strong impressions left by “Carmine Street Guitars,” and this may be more palpable to those who live in New York, is the sense of how much the world—and New York—has changed. The changes have not been good. Carmine Street Guitars is a “relic,” in a way, of a West Village that no longer exists. New York is now so much a city for the rich that the West Village has been decimated by ballooning rents and brand-name stores cutting a swath through independent ownership. (There’s an extremely awkward “scene” where a realtor stops by to ask Kelly questions about the building.) Carmine Street Guitars is an oasis, a quiet place devoted to one specific thing, and one thing only, an artist and craftsman who has been doing it for decades, and will continue until he drops. The sense of the past flows through the film. Honoring the past is seen as reactionary in some quarters. Not here. These guitars, made from wood pre-dating the Civil War in some cases, are a living legacy to the past, “the bones of old New York” as Kelly calls it. Kelly explains how old wood is better for guitars, the scars and imperfections help the sound, the vibrations. These are one-of-a-kind items. Assembly lines can’t create them. Creating a space for Kelly, his work, the slow vibe of life in his store, its devotion to one thing, is a beautiful act of tribute in and of itself.

There’s a moment where Charlie Sexton, from Bob Dylan’s band, stops by and plays the guitar we have watched Kelly create throughout the “week.” The wood comes from McSorley’s Old Ale House, on East 7th Street, one of the oldest Irish taverns in New York. Kelly wanted to make a guitar from McSorley’s wood for a long time. The finished product is a doozy, with graffiti scratched into the wood by McSorley’s customers left intact. Sexton loves the guitar, and plays the old Sophie Tucker song “Some of These Days,” with its opening lines, “Some of these days / You’ll miss your honey …” One of these days, Carmine Street Guitars might be gone. That eagle-eyed realtor is ominous, he is the bane of West Village existence. In this precarious context, Cindy Hulej takes on enormous importance. Kelly is passing on his craft to a younger generation, just like artisans did in the old days. There’s hope.