The ravishing images in “Carmen” evoke a powerful sense of myth, poetry, timelessness, and dreams. Each shot is exquisitely framed, every detail contributing to the haunting mood. Cinematographer Jörg Widmer, who was on the camera crew for a similarly dream-like setting with “The Tree of Life,” gives settings that might otherwise be desolate or grimy a sense that even the bleakest environments can be beautiful, even romantic. Director Benjamin Millepied’s first feature reflects his background as a dancer and choreographer. The dance numbers are pulsatingly, pulse-poundingly erotic, and gorgeously performed and filmed. Nicholas Britell’s score has touches of an angelic choir that sometimes seems to be commenting on the story like a Greek chorus, carrying the characters forward, caressing them, or sounding an alarm. All of that makes “Carmen” a fever dream love story of heartbreaking beauty. The name Carmen, we are told, means poem.

It begins with a lone flamenco dancer performing alone on a wooden board laid across the sand in the middle of a Mexican desert. Her staccato taps seem to spell out in Morse code the thoughts we hear about men and the trouble they bring. And then one arrives, bringing trouble. He asks, “Where is she?” The dancer ignores him, tapping ever faster. And then he shoots her.

As she dies, she tells her daughter to go to Los Angeles and find Masilda (Rossy de Palma). “If you are my heart,” she says, “she is my spine.” That daughter is Carmen (Melissa Barrera of the underseen “In the Heights”). She smears her mother’s blood on her forehead and sets off for the United States.

Then there’s a bit of an (intentional) jolt with a switch to a more contemporary scene, with Aiden (Paul Mescal) barbecuing at a small party, gently turning down a beer from a woman who seems interested in pursuing a relationship, gently teasing his sister about the way she looks out for him. He is a veteran and at something of a loss. At night, he plays his guitar alone in the desert.

He and some of his friends are volunteer (unofficial, uninvited, and trigger-happy) border guards. Carmen is captured, and her friends are shot. Then Aiden kills the man who is about to shoot her. Soon they are on the run together.

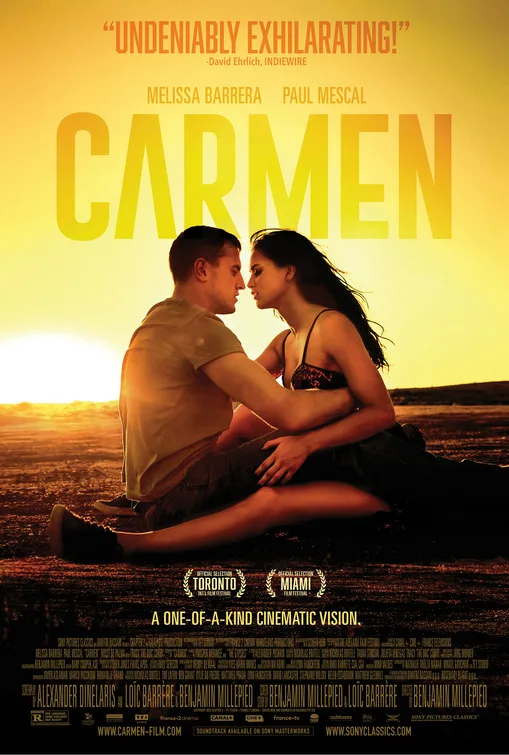

Barrera is a wonderfully graceful and expressive dancer. She and Mescal have sizzling chemistry that works on an emotional level, not just a physical one. Their characters connect without words, recognizing loss in each other and understanding how they respond to what they have lost. Mescal continues to be one of the most arresting actors in film today. No one is better at using posture and movement to define a character. Aiden may have been separating himself from others and his past when we first see him. He drinks Pepsi while others around him drink alcohol, which suggests that he is may regret some past choices. But his sense of honor is intact. Mescal beautifully shows us how he feels when he finds that he may still be open to love and connection.

There is only the slightest link to the classic Carmen story from the Prosper Mérimée novel that inspired the Bizet opera and many variations, including a ballet, Carmen Jones, and more than a dozen other film adaptations. Though the story concerns love and loss, the characters and their relationships are completely different. Aiden and Carmen seem to be fated to be lovers, but just as important to the story is “the spine,” Masilda, a formidable dancer who owns a nightclub in Los Angeles. She welcomes Carmen and Aiden as though they were her long-lost children. Tellingly, it is only when Carmen dances with Masilda that she cries, finally sobbing over the loss of her mother. Millepied makes dance the heart of the film, the way the characters express what they are feeling, the way they set the scene and tell the story. One deeply affecting dance number may not be “real” even in the dreamscape of the film. But it tells us everything the characters do not have the words—or the time—to tell each other.

It is also telling that Millepied makes de Palma, one of Pedro Almodóvar’s favorite performers, central to the story. It does not have the same kind of melodramatic soap opera storyline; nothing could be simpler than a couple on the run, discovering that they love each other. But as in Almodóvar’s films, the heightened use of color and settings is stunning, and the filmmakers are not afraid to express passionate emotion. That creates movie magic.

Now playing in theaters.