In 1977, when she is 53 and near the end of her life, the great diva Maria Callas is approached by a man who directed some of her greatest performances. He wants to film her in “Carmen.” Impossible! she says, playing him a tape of her final concert, in Tokyo, where the great voice was in ruins.

His idea: Use the Callas of today and the voice of Callas in her prime. “But — it’s dishonest!” she says. Still, since almost all European movies until recent years were lip-synched anyway, it is not such a transgression as it seems, and it would at least make possible the great opera film that Callas never made.

This fictional story, told in “Callas Forever,” has parallels with real life. Franco Zeffirelli, who directed and co-wrote the film, directed Callas on stage in “Norma,” “La Traviata” and “Tosca.” In 1964, he directed her TV special “Maria Callas at Covent Garden,” and he remained a friend of the singer until the end. In addition to his famous feature work like “Romeo and Juliet” (1967) he directed several films of operas, notably “La Traviata” (1982) and “Pagliacci” (1982) with Placido Domingo and Teresa Stratas, and “Cavalleria Rusticana” (1982) and “Otello” (1986), with Domingo. He must have dreamed of one grand final film for Callas, and might even have spoken with her about it.

What else in the movie is based on fact, we cannot know. Terrence McNally’s play “Master Class,” which shows Callas teaching opera students, shows her at a similar time in her life, but the story structure of “Callas Forever” is original, and pointed in another direction. It is perhaps Zeffirelli’s consolation for the film he was never able to make. (It is small consolation, however, for Faye Dunaway, who starred powerfully in “Master Class” for a year and dreamed of making a film version of the play.)

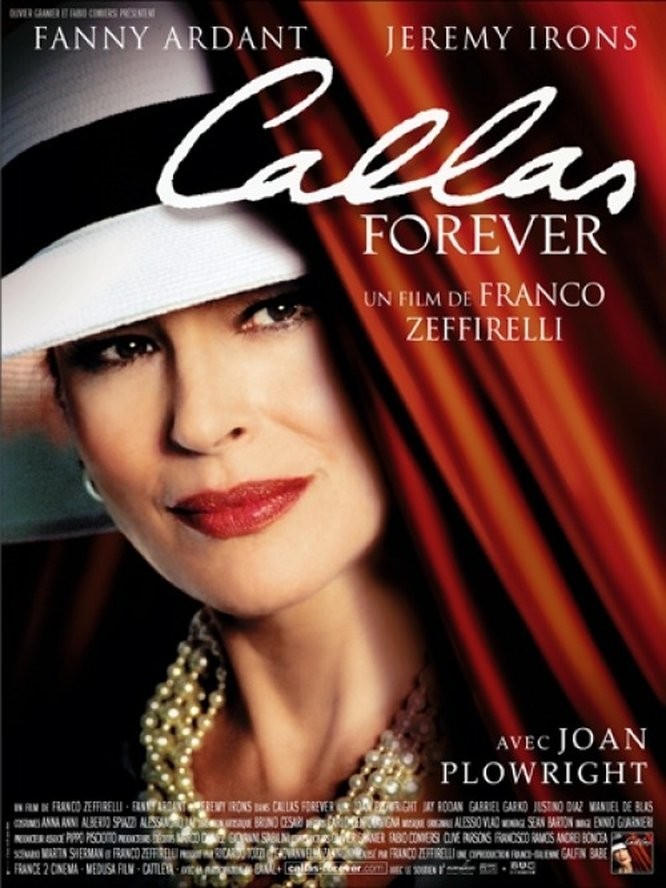

Callas is played in “Callas Forever” by Fanny Ardant, that tall, grave French actress with the facial structure of a Greek heroine (one thinks of Irene Papas in “Electra”). Ardant (who starred in Paris in “Master Class”) cannot sing, but then neither could Callas at the time. What she does have is the fiery passion needed for “Carmen,” and Zeffirelli stages several scenes from the opera in the style, we can only assume, that he would have used had he made the actual film. These show Callas in her impetuous, imperious, man-scorning pride, physically dominating the production. And the voice is … Callas.

The visual style is all Zeffirelli, and it is interesting that the opera-within-the-film is not skimped on, as is usually the case in films containing scenes from other productions. Indeed, most of the budget seems to have gone to the moments of “Carmen” that we see; they look sumptuous and robust, and the surrounding film looks, well, like a low-budget art movie.

Callas shares the story with Larry Kelly (Jeremy Irons), probably meant to be Zeffirelli, a hard-working professional director, gay, whose infatuation with a young man named Michael (Jay Rodan) seems like a slight embarrassment, and seems meant to be; Kelly drags Callas over to the youth’s studio to look at his paintings, and Callas praises him because she knows that at some level Larry has to deliver her as part of his romantic bargain with Michael. These scenes are a distraction, and slow down the main line of the movie.

Ardant excels at playing a temperamental diva, whose entrances transform a room, who is instantly the center of attention, who gives orders and expects to be obeyed. This is all true to life. Callas was famous in a way no other 20th century opera singer was famous, and she deserved her fame, not only for the toll she paid through her celebrated liaison with Aristotle Onassis but also because her voice was called the voice of the century, and that may have been true.

Her problems with “Carmen” involve more than the dubbed soundtrack. She is concerned about how she looks. Half-persuaded she should let her fans remember her as she was. Uncertain about a flirtation with a young man on the set. And for that matter, just generally flighty on principle, as a diva has a right to be.

The Larry Kelly character is patient, flattering, persuasive, insidious. To his credit, he seems to want to make the film not so much for himself as to collaborate with Callas on a film she should have made and never did. But there is a crucial moment when he visits her apartment late at night and sees her singing along with her recordings and then sobbing, and he realizes that anyone who sang as Callas did must always live with the pain of having lost her gift.

“Callas Forever” reminded me a little of two documentaries by Maximilian Schell, “Marlene” (1984) and “My Sister Maria” (2002). Both were about great beauties, now reclusive. His friend Marlene Dietrich refused to be seen on camera. His sister Maria did not. Dietrich made the wiser decision, and in “Callas Forever,” we are asked to decide if Callas does, too.

Note: It is amusing, in a movie where dubbing is one of the subjects, that the opening airport scene is so poorly dubbed.