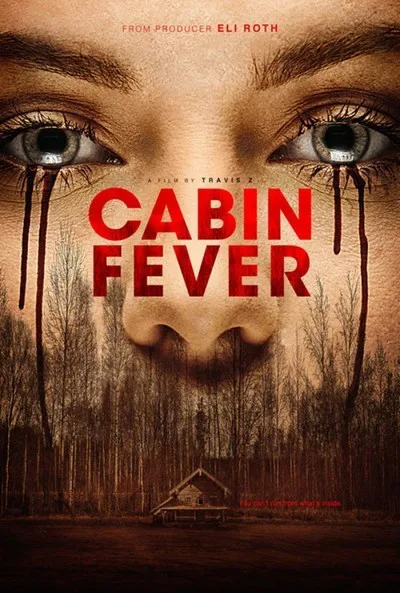

One of the most appropriate ways to review a film like “Cabin Fever” would be to copy and paste Roger’s words on Eli Roth’s 2002 original. Yes, this is one of those questionably greedy, xeroxed remakes, where its business is in restating, not just restarting or rebooting, what the original has done. Yet what backfires in particular about this head-scratching endeavor is that the movie is made for horror junkies, a specific bunch that does not forget—in terms of their cherished titles (even from 2002), and those who dare put their marks on them.

A remake of “Cabin Fever” could develop itself in an imaginative way, but opts instead to echo huge chunks of the original. At least, some characters die in different ways, and one of the bigger characters (a deputy) has been recast as a woman. For slight rebranding, the events are all bookended on more serious notes, which creates an overall ho-hum affair out of young people being slowly skinned alive.

The drama involves the characters going through the same motions as Roth’s movie, a fatalistic course of events where terrible luck, ugly compassion and a tsunami of blood meet. A pale band of college-age people (played here by Gage Golightly, Matthew Daddario, Nadine Crocker, Dustin Ingram and Samuel Davis) venture out from the city to the countryside, fool around in a place by the lake (don’t let the title fool you, this is a lake house) and most detrimentally of all, drink the water. We know the cause of the virus comes from the lake long before they do (whether you’ve seen the original or not) and we wait for them to in all literal senses fall apart. As the characters do so during the story’s sometimes muffled slow burn, Roth’s charcoal sense of humor is missing, the cruel irony lacking its hellish zing. Director Travis Z’s version of “Cabin Fever” does not end with a lemonade stand.

The film does make a convincing nudge for Roth appreciation, showing the confidence of Roth’s debut by lacking much of its own. At the least, it makes one appreciate even a tiny bit more the macabre cleverness behind the story’s set-up and execution, a filthy mess of social class tensions and grotesque acts of humanity, where the answer to putting someone out of their misery is setting them on fire. Roth’s visuals are not scarring by accident—the ominous close-ups of a generous glass of water, a woman shaving her legs in a bathtub to only realize she is flaying herself—but Z repeats them here with zero immediacy.

Using the same script Roth co-wrote with Randy Pearlstein in 2002, Z’s noteworthy touches feel to be more aesthetic and in collaboration, like Kevin Riepl’s explosive and appropriately screeching score, or Gavin Kelly’s wide shots of a calmly menacing lake. The otherwise stubborn nature of the movie blankets many other elements, like its decent performances that alternate between chillin’, screaming and weeping. There isn’t much character for them to individually fulfill, but their game nature distracts from that often with no problem. With and without them, the film adds up to a lot of bad ideas and very few good ones, wandering around Roth’s footsteps in search of purpose.