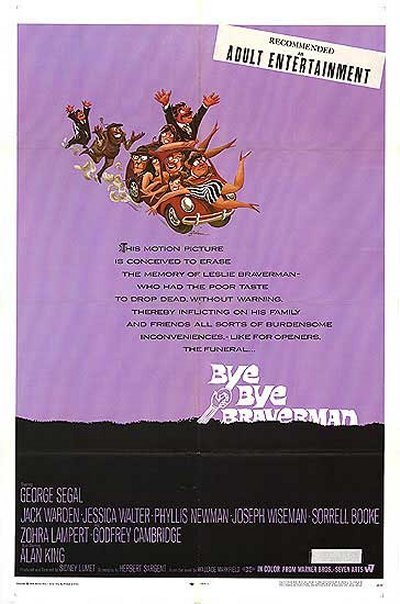

Sidney Lumet’s “Bye Bye Braverman” is a good movie gone wrong. Its premise was promising: Four liberal Jewish intellectuals learn that one of their friends, Leslie Braverman, has dropped dead at the untimely age of 41. They set off together in a Volkswagen to attend his funeral, but at some time during that long Sunday afternoon their trip turns into an odyssey of unfulfilled ambition, bittersweet comedy and the fear of death.

We never met Braverman. But we meet his bitchy wife (Jessica Walter), whose “sophisticated” cruel treatment of her daughter gives us a hint of what Braverman had to put up with. And we meet his friends: George Segal, a public relations man; Joseph Wiseman, a Norman Thomas socialist; Sorrell Booke, a compulsively tidy writer, and Jack Warden, an aging playboy.

When they learn of Braverman’s death, they meet in Greenwich Village and drive to Brooklyn. They can’t quite find the funeral, but they run across strange creatures: Godfrey Cambridge, as a sort of black Jewish taxi driver; Alan King, as a rabbi; and a strange lady at the wrong funeral. They also pass a lot of colorful real estate, lovingly photographed by Lumet, who also goes up in a helicopter to show the Volkswagen scurrying under overpasses.

Segal, the central character, has fantasies of his own failure and death. It would be better to die young, he muses, than to die in the middle of things at 41. Better to do nothing at all than to get stopped halfway. He ponders these questions as they search for Leslie Braverman, departed.

This is Lumet’s first comedy. He usually makes social dramas (“Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” “The Pawnbroker,” “A View from the Bridge”), and the timing of “Bye Bye Braverman” seems more suited to a serious mood than to humor.

There is also a tendency to slip into exaggerated Jewish stereotypes: Alan King’s rabbi is particularly offensive, and other characters speak a dialog that rings as false as stage or music hall German. Segal himself played a much more subtly delineated Jewish character in “No Way to Treat a Lady.”

The movie has its moments. There is a scene where Segal wanders through one of those endless New York cemeteries. It is shot with a telephoto lens, and begins with Segal as a speck among a universe of gravestones. Segal crisscrosses his way closer to the camera, which moves in on him very slowly during a long speech. He tells the dead what has happened in the meantime. The shot ends in close-up.

Good things like this do not redeem “Bye Bye Braverman’s” slow pace, however; and this must be reckoned a movie for buffs who want to observe Lumet’s studied, rich style. A general audience would probably find it dull, and would probably be right.