Polish director Agniezka Holland’s new miniseries, “Burning Bush,” playing in New York at the Film Forum and streaming online at Fandor, is deliberately not epic. Holland has never prized spectacle over incident. There are no matte painting landscapes teeming with extras; no big speeches that give us the moral with a bow tied around it; no easy answers and few satisfying endings. Her films are set in an unfair past, which would be all blue, grey and black if it weren’t for all the bloodshed.

“Burning Bush” may concern dozens of characters over the course of many months during a tempestuous time in a city under siege, but the emphasis is on people in cramped rooms, trying and failing to make sense of what’s happening outside their windows. Time and again, characters look out at the world and see only danger, whether because of the men parked outside their houses in the small hours of the morning or because a dark figure is trying to open a locked door. Even more frequently, Holland’s characters find themselves in mirrors; their own reflections the only thing that grounds them. She minimizes sprawling political conflict to tired faces and the seemingly insignificant objects and gestures that give life meaning.

The year is 1969. Russian troops invaded Czechoslovakia the year prior to stop a threatened push toward socialist reform, courtesy of Communist Secretary Alexander Dubcek. In protest, a student called Jan Palach took to the streets, doused himself in gasoline and lit a match.

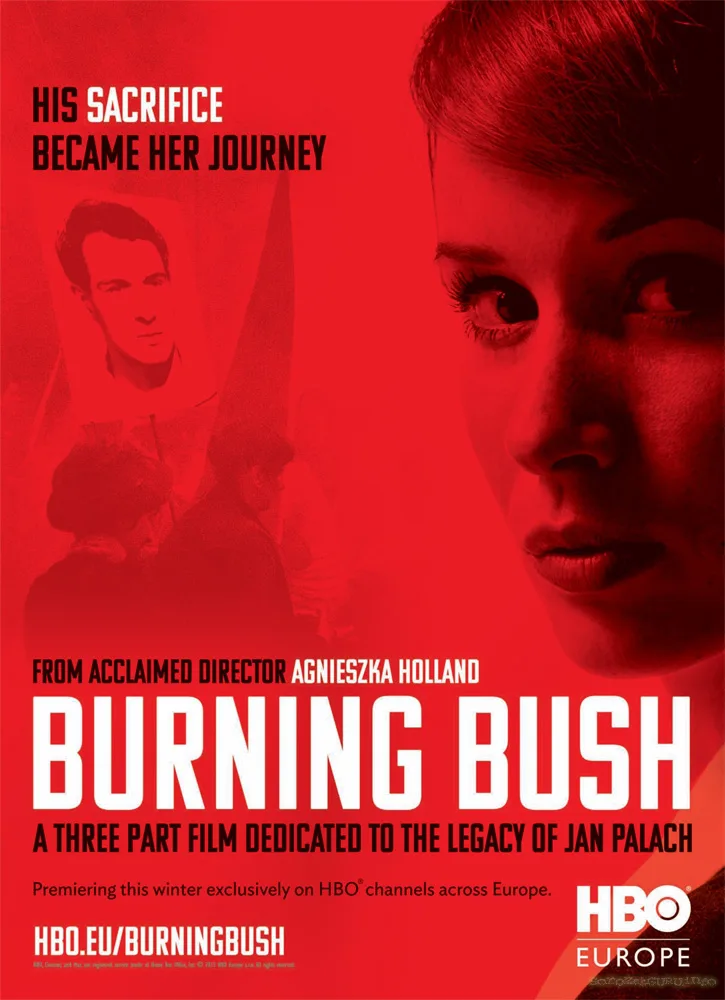

“Burning Bush” examines the aftermath of this event in three parts, each with its own generic shape. Part one concerns the chaos that spreads to every corner of Prague. Put-upon Czech police try to divine Palach’s motives without upsetting the Russian officials to whom they answer. Meanwhile, the members of Palach’s student protest group try to carry on in his name, and Palach’s mother (Jaroslava Pokorná) and brother (Petr Stach) try to deal with both their grief and seeing their loved one serve as a point of contention between warring political factions. Part two takes the form of a conspiracy thriller as Palach’s mother hires Dagmar Burešová (Tatiana Pauhofová), a young attorney, to sue a party official for slandering her son in print. In response, the collaborationist Czech government intimidates Mrs. Palach, Burešová and her family. Part three is a courtroom drama as Burešová finally gets the case to trial. She and her assistant are thrown into disarray as their leads start to dry up, due to coercion and sabotage.

“Burning Bush” has many different historical and artistic strands in its DNA. Holland has always drunk deeply and appreciatively from the well of Polish cinema; her brilliant 2011 film, “In Darkness,” is a tribute to Andrzej Wajda’s 1956 masterpiece “Kanal.” Here she cribs a shot from Wajda’s “A Generation,” not only because both films are about resistance, but to remind her audience how important it is that we never stop looking back through history. Holland quotes Wajda the way post-punk singers like Ian Curtis of Joy Division used to quote J.G. Ballard or the way Ian McCulloch of Echo & The Bunnymen used to quote Camus. It’s enlightening shorthand.

Holland never risks overlooking the hardship that comes with being on the right side of history. “Burning Bush” is a riposte to the idea that there’s anything beautiful about dying for your beliefs. Lindsay Anderson once wrote that “Revolution is the opiate of the intellectuals,” and Holland has never partaken. She’s never allowed herself to get swept up in the romance of change, never turned a blind eye to how desperate life can look when the powers that be have decided it isn’t worth anything. Whether it’s a boy confined to a wheelchair in “The Secret Garden” or a disparate group of people living in a sewer in “In Darkness,” Holland’s heroes have been forgotten by everyone but themselves.

Palach setting himself ablaze provoked an incredulous reaction from the government and public alike. No one wanted to understand. So the opposition wrote their own song to turn him into a myth, a lunatic victim of socialism, but they couldn’t agree on a tune. It was suicide, they said. He was insane. He faked his death. He was coerced, anything but rational and sane. The greatest struggle the heroes in “Burning Bush” face is proving that Palach was a human being who wasn’t content to let totalitarianism crush idealism. The officials on trial know they’ll have an easier job discrediting Palach’s actions if they say he’s a pawn or crazy. If he’s just a person, like anyone else, then they’re responsible for his death. They try time and again to change the minds of the tireless Parlachs and Burešová, and, when that fails, they just change the properties of their world because they’ve been granted that terrifying power. How does one retain their humanity when the state’s at work 24 hours a day looking for new ways to disenfranchise the hopeful? The film’s most devastating shot goes literally through a wall to reveal a gang of operatives listening to a conversation, deciding ahead of time how it will end. Suddenly every mirror could have been home to anonymous ears and eyes, always watching, always a step ahead. It turns out that not even reflections can be trusted.

In the end, all that can be relied upon are objects and gestures. The littlest things that tie us to each other. The film often slows to a standstill to show children playing, cars passing, people talking and streets emptied of traffic. Life, in short, going on, despite the war raging nearby. Upon learning of his brother’s death, Palach’s brother Jiri is given a lift in an ambulance to his mother’s house to tell her the news in person. The driver shares a cigarette with him on the way. A few weeks after his death, Palach’s mother has her son’s belongings returned to her by the police. In the film’s most bewitching scene, Palach’s comrades in the student movement pay a morgue attendant off so they can get to their friend’s body. Once there, a sculptor takes a plaster cast of his face which is then placed in public view at their school. In the opening of Part 1, a crowbar digs into a muddy street, diverting the course of an oncoming train. A few feet away, a man strikes a match diverting the course of a nation. It doesn’t get any less epic than that.