He was 24 when he had sex for the first time. She was a 300-pound prostitute. He remembers her name. As he tells the story, he does an extraordinary thing. He blushes. Here was a man who made a living and became a legend by being hard-boiled, and he blushes, and in that moment we glimpse the lonely, wounded little boy inside.

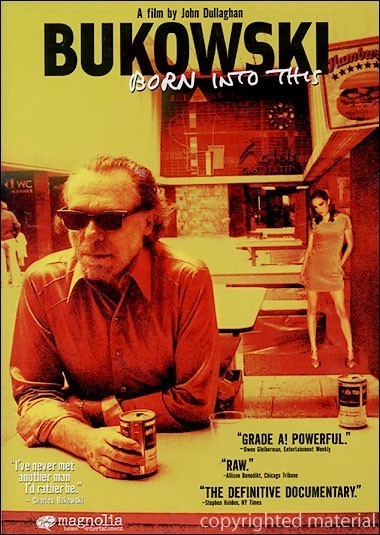

John Dullaghan’s “Bukowski: Born Into This” is a documentary about the poet and novelist who died in 1994. It draws from many interviews, from footage of poetry readings, and from the testimony of his friends, who include Sean Penn, Harry Dean Stanton, Bono and the publisher John Martin, who started the Black Sparrow Press specifically to publish his work. There are also the memories of his wife, Linda Lee Bukowski, who loved him and cared for him, despite scenes like one in the film where he kicks her and curses at her.

That was the booze talking, you could say, except when precisely was Bukowski sober? He drank with dedication and abandon for most of his adult years, slowed only by illness toward the end. And he chain-smoked little cigarettes named Mangalore Ganeesh Beedies. “You can get them in any Indian or Pakistani store,” he told me in 1987. “They’re what the poor, poor people smoke in India. I like them because they contain no chemicals and no nicotine, and they go very well with red wine.”

Linda Lee Bukowski, it must be said, possessed extraordinary patience to put up with him, but then she understood him, and his life was often as simple as that: A plea for understanding. I sense from his work and from a long day spent with him that even when he was drunk and angry, obscene and hurtful, he was not the aggressor; he was fighting back.

The movie opens with Bukowski on a stage for a reading, very drunk, threatening to come down into the audience and kick some ass. There is another reading where, backstage, he asks the organizer, “You got a little pot on the stage I can vomit in?” He drank most every day, red wine for preference, and his routine usually included a visit to the track, a return home, and long hours at his typewriter with classical music on the radio. For all of his boozing, he was, like the prodigious Thomas Wolfe, amazingly productive.

He wrote poems as if the words were bricks to be laid. He cut through the labyrinthine indulgent difficulty of much modern verse, and wrote poems anyone could understand. Yet they were poems, real poems, and the film director Taylor Hackford remembers the first time he head him reading; he was presented by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, one of the founding Beats, at Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Bookstore in San Francisco — where to this day you can find a shelf of Bukowski, most of it with the bold Black Sparrow lettering on the spine.

John Martin, the publisher, says he offered Bukowski a monthly stipend to live on, with the condition that he quit his job at the post office. One of his first novels was Post Office, a snarl at the daily torture of hard work under stupid bureaucrats. It snarled, yes, but it also sang, and was romantic and funny. It came directly from Bukowski’s life, as did such autobiographical novels as Women and Hollywood.

The Hollywood book was inspired by his experiences when his Barfly was adapted into a movie starring Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway. He didn’t like the movie much — he thought Rourke was a “showoff.” I thought it was a good movie and wondered if part of his dislike was because he was played by a handsome man who had never suffered the agonies of being Charles Bukowski. It is probably also true that in his barfly days he was rarely fortunate enough to be the lover of a woman who looked like Faye Dunaway.

On the set one day, Dunaway turned up to question him, doing research on the character she would play.

“This woman,” she asked him “What would she put under her pillow?”

“A rosary.”

“What sort of perfume did she wear?”

He looked at her incredulously.

“Perfume?”

I can testify to the way his life became his fiction, because the day I spent on the set of the movie became part Hollywood, and the movie critic in the book is a fair enough portrait of me. Central to his fiction and poetry was his lifelong love-hate relationship with women; by the time his fame began to attract groupies, he complains, “it was too late.”

The movie is valuable because it provides a face and a voice to go with the work. Ten years have passed since Bukowski’s death, and he seems likely to last, if not forever, then longer than many of his contemporaries. He outsells Kerouac and Kesey, and his poems, it almost goes with saying, outsell any other modern poet on the shelf.

How much was legend, how much was pose, how much was real? I think it was all real, and the documentary suggests as much. There were no shields separating the real Bukowski, the public Bukowski and the autobiographical hero of his work. They were all the same man. Maybe that’s why his work remains so immediate and affecting: The wounded man is the man who writes, and the wounds he writes about are his own.