“Brothel Eight” is perhaps the worst possible title for a film that’s intended as a thoughtful, compassionate document. The worst title, that is, until we’ve seen the film and understand the implications of its stark simplicity. It stands for a system of compulsory prostitution that flourished in the poorer islands of Japan until well into this century – so recently, indeed, that some of the prostitutes still survive. The film is the story of one of them.

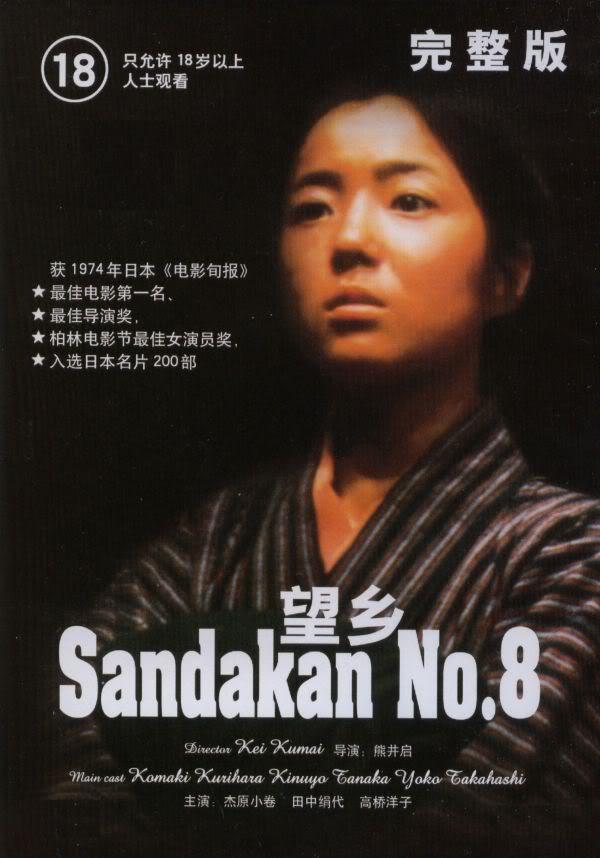

It’s told from the point of view of a young, female, Japanese graduate student, doing research on the “karayuki-san” – the very young girls who were shipped to such places as Borneo and Vietnam to work in brothels. The student visits one of the smallest Japanese islands, and learns through a chance remark dropped in a cafe that the old lady she’s talking to was once a karayuki-san. The old woman, for her part, pretends that the girl is her daughter-in-law – the wife of a son she never sees, although he sends money once a month. She brings the student back to the tattered hut she lives in at the edge of the forest, and gradually she tells her story. We see it in flashbacks. How she was sold to pimps, was shipped to Borneo, worked as a whorehouse maid for a few years before being forced to become a prostitute. This material is sensitively handled; the movie is not explicit (and is, indeed, tasteful enough to have won a Japanese Academy Award as the year’s best film.)

Through the memories of the old woman, we meet the customers she serviced (and the one she fell in love with.) And we meet the proud madam of one of the houses, Kiku, who takes a certain pride in her profession, and is completely lacking in hypocrisy. These scenes are interesting – but more moving, for me, is the gradual development of the friendship between the old woman and the young student. The woman continues to pretend the girl is her son’s wife, but we find out eventually that that’s only a fantasy she clings to. She’s actually accepted the girl as a friend.

The old woman’s neighbors are scandalized that she’s telling the girl of her life as a prostitute. “She’s just a journalist from Tokyo,” they sneer. “She’ll shame you in the newspapers and you’ll lose all your friends.” No matter; the old woman has made her decision. When the girl confesses that she is, indeed, a writer, the woman calmly invites her to go ahead and write the story – just being sure to get it right. And then the two women share a moment of truth – each confessing her own real thoughts – that’s the nicest in the film.

There’s an epilog. The old woman has told the girl about a graveyard Kiku established for the prostitutes who died. The girl hires guides and goes into the jungle of Borneo, seeking the site. She finds it, and as the underbrush is hacked away from the grave markers she realizes that all of the graves face in the same direction – away from Japan.