Small towns live and die according to what seem like whims of fate. But just as every great fortune has its origin in a great crime, every small town that survives has a particular economic motor. Some are more interesting than others. The Mexican town of Tulpatec survives through pyrotechnics.

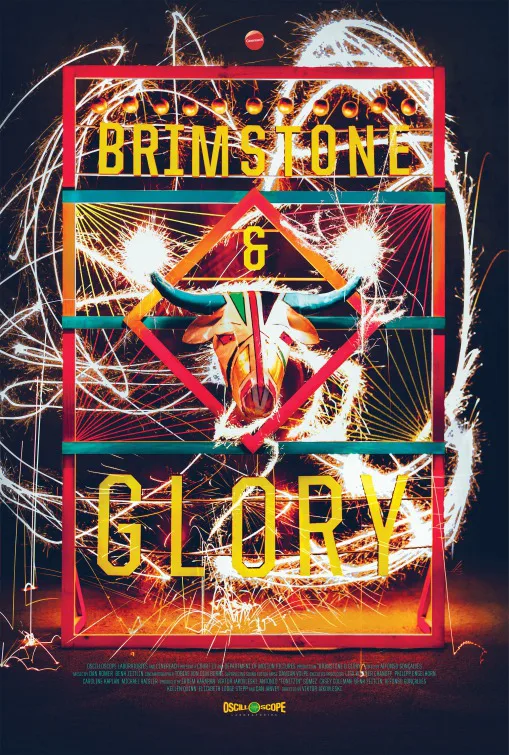

“Brimstone and Glory,” directed by Viktor Jakovleski and backed by some of the talents behind “Beasts of the Southern Wild,” is a documentary about that town’s annual Pyrotechnics Festival, an event that, it seems, is prepared for year-round by its residents. The fireworks engineered in this place, north of Mexico City, aren’t Macy’s Fourth of July high-tech displays, precision engineered and digitally controlled. But they’re not crude either. One hallmark of the festival is the evening devoted to large sculptures of bulls, each one packed with explosives. The point of this display is to have the bull as a launching site for various light-and-sound spectacles while never burning or in any other way damaging the sculpture itself. It’s like creating a candy-dispensing piñata that remains whole. There’s a lot of ingenuity required.

And there’s a lot of danger involved. Injuries during these festivals are common. Town elders tend to be cheerful fellows who are missing an eye or a limp or several fingers. Young kids working on fireworks projects are praised for having “gunpowder in the blood.” The film doesn’t have to push hard on a thesis about how economy determines culture. The town is an organic demonstration of it.

There are religious roots to the festival. It’s dedicated to a Portuguese saint who, according to legend, rescued the patients of a burning hospital without suffering a single burn. The day-to-day life of the town is lived in constant proximity to deadly materials—large signs reading “Peligro” are everywhere. The scenes of the preparations of the explosives are fascinating, particularly because everything is so analog. Mortar and pestle are primary tools in mixing powders and dyes.

And once the big day arrives, the nimble cameras operated by Jakovleski and his team get some awesome visuals. This is a movie that repays being seen on a big reflective screen, one on which the image is projected rather than one from which the image emanates. Because the light that comes off of the screen is strong and fierce. It’s exhilarating and scary at the same time.

The mode of this short movie is naturalistic. There are interviews of people in voiceover, but not a lot of talking-head footage. The perspective is of an observer sauntering through the town and then thrust into the middle of a fearsome but exhilarating spectacle. “Brimstone and Glory” took three years to make. I think the filmmakers needed that time to come up with a result that seems so simple and straightforward, yet has such deep resonance.