McElwee is a great-grandson of John McElwee, who patented the famous line of Bull Durham tobacco. John McElwee and Washington Duke, founder of the Duke dynasty, were rivals at the birth of the modern tobacco industry, and Duke essentially destroyed McElwee (whose warehouse was burned down three times by suspicious fires). The Dukes went on to found Duke University. Three generations of John McElwee’s descendants became doctors, and Ross became a documentarian who films introspective essays about his life.

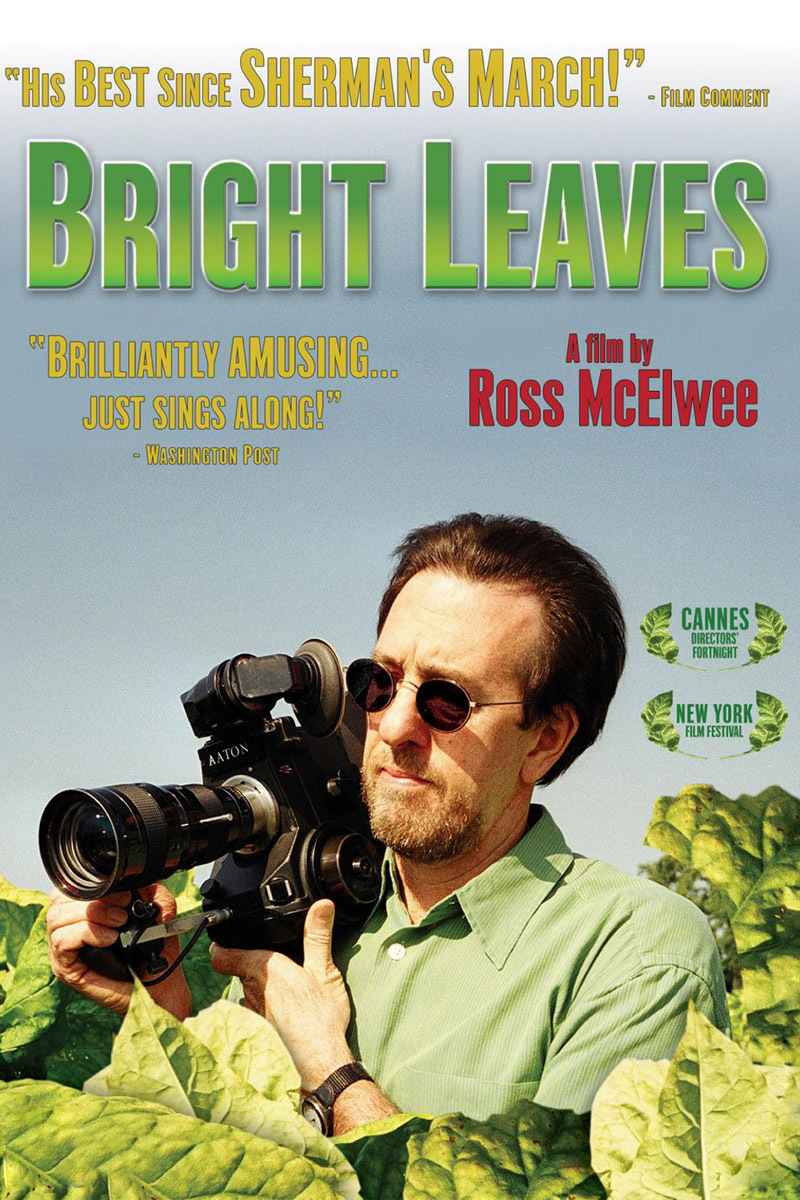

“Bright Leaves” is not a documentary about anything in particular. That is its charm. It’s a meandering visit by a curious man with a quiet sense of humor, who pokes here and there in his family history, and the history of tobacco. The title refers to the particular beauty of tobacco leaves, both in the fields and after they have been cured, and perhaps also to the leaves of his family’s history.

McElwee’s odyssey begins with a second cousin, a fanatic film buff, who is convinced that “Bright Leaf,” a 1950 movie starring Gary Cooper and Patricia Neal, was inspired by the rivalry of Washington Duke and John McElwee. There do seem to be a lot of parallels in its story of the triumph of one family over another. McElwee interviews Patricia Neal, who knows nothing about the origins of the story, but does helpfully volunteer that Cooper was “the love of my life.” Then he tracks down Marian FitzSimmons, the widow of the screenwriter, who assures him her husband did not have real people in mind.

Well, maybe not, but the parallels are uncanny. Unwilling to entirely let go of his notion, McElwee wanders about the area where he grew up, remembering that his childhood home, while large and comfortable, was known as the “Duke’s outhouse.” He ruminates on the addiction of smoking, which he has given up while still understanding its appeal. He chats with five beauty school students as they puff away on the sidewalk outside their classes, and with a couple who give him their deadlines for stopping smoking: When they get married, after the millennium, whenever. He also visits people who are dying of cigarette-related illnesses, but he doesn’t preach about the evils of tobacco; it’s more that he regrets that such a beautiful plant, which produces so much pleasure, should be lethal. Think how happy it would make so many people if smoking were good for you.

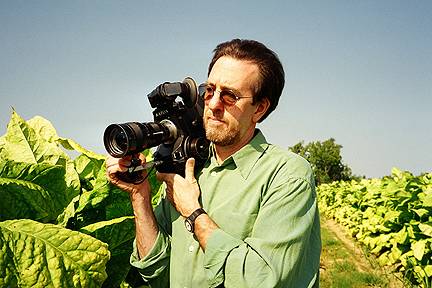

McElwee’s lifework is his life. He has been making autobiographical films since 1976, taking as his subjects his father, his Southern heritage, his favorite teacher, his marriage, his son, his prospects. His most famous work is “Sherman’s March” (1986), which traces the footsteps of the Civil War general while musing about Southernness and whatever else occurs along the way.

In all of his films, McElwee runs into people by chance, and pauses to film them. In “Bright Leaves,” one of his discoveries is Vlada Petric, a film historian he consults for information about the Gary Cooper film. Almost immediately, the subject becomes not Gary Cooper, but Vlada Petric, who refuses to be interviewed in one of those boring shots where the camera looks at a guy sitting in a chair. Instead, Petric orders McElwee to sit in a wheelchair with his hand-held camera, while Petric looms over him, pushing the chair backward while being interviewed. Petric is right and the shot is interesting, but not as interesting as the shots of Petric insisting on it.

Others we meet along the way include Charleen Swansea, the inspirational teacher who has been in several of McElwee’s films, and now talks about her dying sister, a smoker made ill by cigarettes. He talks with a civic booster about Charlotte’s Tobacco Festival and its annual parade, only to discover that, starting next year, it will be renamed Farmer’s Day. He finds that local residents have “mixed feelings” about tobacco, which has been so good to them financially and yet killed so many along the way.

McElwee’s films are always, in a way, about why he makes them. He looks at faded home movies of his father, trying to recapture his memories of the man, and then he films his son and wonders how the son will feel, some day, seeing this film. Always at his back he hears time’s winged chariot, hurrying near, and is fascinated by the way film seems to freeze time, or at least preserve it. He doesn’t really much care that his family lost an incalculable fortune to the Dukes; he is content to be who he is, doing what he does, and his motivation for making the film is not to complain, but simply to meditate on how events in the past reverberate in our own lives. He goes back to the park and sits on the bench again. McElwee Park. It’s not much, but it’s something.