The animation in “Boy and the World” initially may seem as simple as the title itself.

A stick-figure child in a red-striped shirt with a round head, three sprigs of hair and a pair of dark, vertical slashes for eyes occupies a blank, white screen. He doesn’t even have a name (although press materials refer to him as Cuca) and doesn’t really speak so much as giggle, and the limited dialogue that does exist in Brazilian writer-director Ale Abreu’s film consists of meager sprinklings of gibberish.

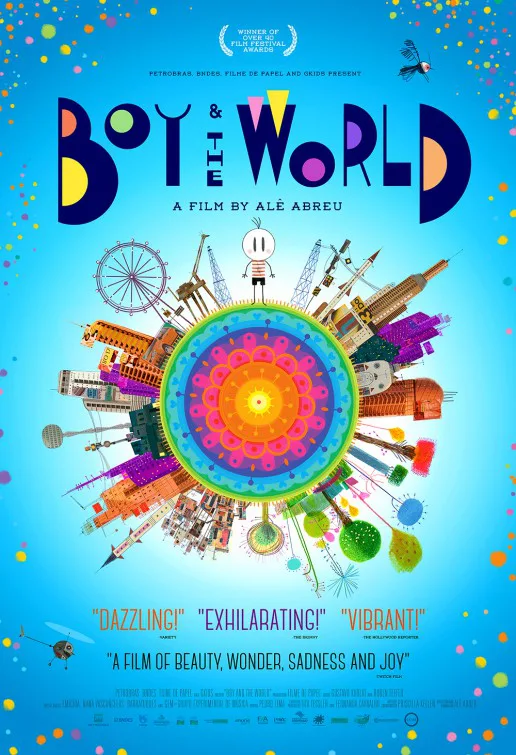

But it doesn’t take long for the vibrant beauty of Abreu’s vision to unfurl and take hold. “Boy and the World” is dazzlingly colorful and alive, often resembling a more elaborate version of the kind of childlike drawings you probably have stuck to your refrigerator door right now. His combination of rich hues and textures and evolving aesthetics makes “Boy and the World” a constant wonder and joy to behold.

As a parable about the perils of industrialization and the gaping disparity between the haves and have-nots, it may not say much that’s new (and it doesn’t say it in a way that’s terribly subtle). But as an artistic exercise, it’s a marvel of imagination. It is at once innocent and cynical, hopeful and hard-eyed.

At the start, the boy enjoys a carefree existence on his family’s farm. He frolics in cool, blue streams and climbs endless trees—so high, he can even bounce around in the clouds. Anything seems possible to him. And yet to us, it’s obvious that his family is struggling. So one day, his father packs a suitcase and hops on a train—rendered as a steam-belching, industrial centipede that snakes away into the distance—to the big city, ostensibly in hopes of improving their financial situation.

(Although the movie’s philosophical stance is always clear, its plot points sometimes are not, and things can get a tiny bit confusing given that all the crudely-drawn characters essentially look the same. I watched “Boy and the World” with my 6-year-old son and the question “Who’s that?” came up a lot. But he also loved the look of the film and the boy’s playful spirit, as well as the infectious, samba-infused score from Ruben Feffer and Gustavo Kurlat.)

Desperately missing his father, the boy dares to journey to the city to find him. Along the way, he meets field hands toiling through long days of picking cotton as well as downtrodden factory workers turning that cotton into fabric. The farther he wanders from home and the closer he gets to the teeming metropolitan center, the darker the look and tone of “Boy and the World” become. The color-pencil pastels of the boy’s rural life give way to garish decoupage in the urban street signs and advertising. The city may tower and glitter from afar, but up close it’s steep, treacherous and overpopulated; imagine favelas stacked on top of each other with trains crammed with miserable, monochrome commuters running through them.

But! Lest you think this is all too depressing to bear, this is still a kids’ movie, and so a few glimmers of joy emerge. Strangers are kind enough to take him in along the way and give him shelter. An enthusiastic dog becomes his part-time companion. And even in the face of an oppressive military presence in this futuristic society, there is always exuberant music that unifies the people and lifts their collective souls. At one point, the song of the common people rises into the air and takes the form of a rainbow-colored bird, while the energy of the police force trying to keep them in line emerges as a combative black eagle.

Heavy stuff indeed for an animated film about a child’s road trip, but it’s a prime example of how “Boy and the World” keeps changing and challenging you, and it never goes in the direction you might expect.