Bobby Jones (1902-1971) was perhaps the greatest golfer who ever lived. Not even Tiger Woods has equaled Jones’ triumph in 1930, when he became the only player to win the U.S. Open, the British Open, the U.S. Amateur and the British Amateur in the same year. Then he retired from competition — still only 28. Odds are good no golfer will ever equal that record — if only because no golfer good enough to do it will be an amateur. Jones also won seven U.S. titles in a row, an achievement that may be unmatchable.

Jones was not only an amateur, but an amateur who had to earn a living, so that he couldn’t play golf every day and mostly played only in championship-level tournaments. This makes him sound like a man who played simply for love of the game, but “Bobby Jones: Stroke of Genius” shows us a man who seems driven to play, a man obsessed; there seems less joy than compulsion in his career, and the movie contrasts him with the era’s top professional, Walter Hagen (Jeremy Northam), who seems to enjoy himself a lot more.

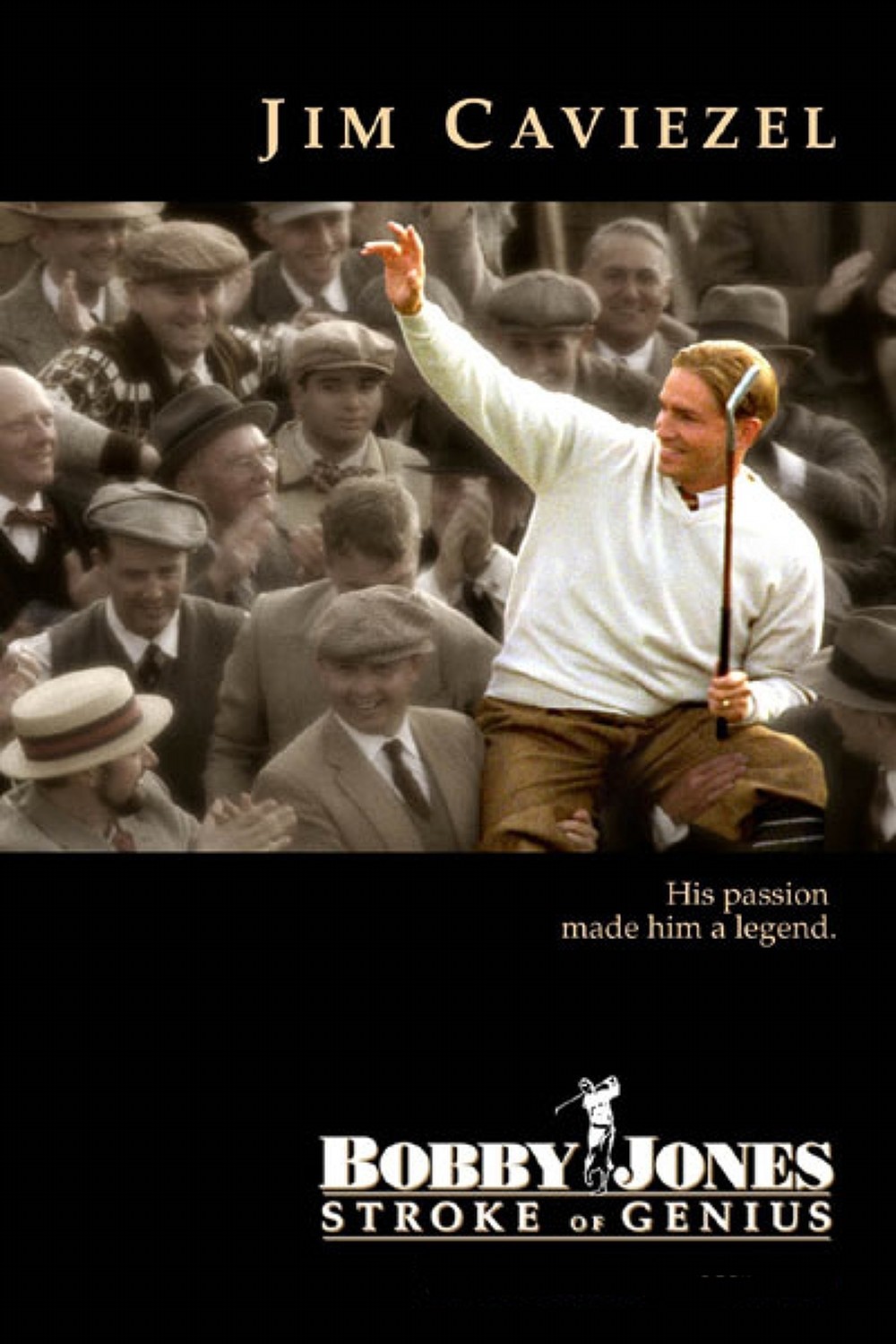

Jim Caviezel (“The Passion of the Christ“) plays Jones as an adult, after childhood scenes showing a young boy who becomes fascinated by the game and watches great players while hiding in the rough. He comes from a family dominated by a strict puritanical grandfather, but Jones’ father, “Big Bob” (Brett Rice) is supportive. Not so Jones’ wife Mary (Claire Forlani), who plays a role that has become standard in the biographies of great men — the woman who wishes her man would give up his dream and spend more time at home with her and the children.

Of course, Mary sees a side of Bobby that’s invisible to the world. The man is tortured. He feels he must enter tournaments and win them, to prove something he can never quite articulate, to show “them” without being sure who they are. And he is often in physical pain. After a sickly childhood, he grows up into a reed-thin man with a tense face, and doctors have only to look at him to prescribe rest. His stomach starts to hurt at about the same time he begins to drink and smoke, and although the movie does not portray him as an alcoholic, we hold that as a hypothesis until we find the pain is caused by syringomyelia, a spinal disease that would cripple him later in life.

“Bobby Jones: Stroke of Genius” tells this story in a straightforward, calm way that works ideally as the chronicle of a man’s life but perhaps less ideally as drama. No doubt we should be grateful that Jones’ story isn’t churned up into soap opera and hyped with false crises and climaxes; it is the story of a golfer, and it contains a lot of golf. Much of the golf is photographed at the treacherous Old Course in St. Andrews, Scotland, where the game began, and where we learn why there are 18 holes: “A bottle of Scotch has 18 shots,” an old-timer explains, “and they reckoned that when it was empty, the game was over.”

A major player in Jones’ life is O.B. Keeler (Malcolm McDowell), his friend and “official biographer,” and if Jones was an amateur golfer, Keeler seems to be an amateur biographer, with all day free, every day, to follow Jones around, carry his stomach medicine (and his whiskey), and chronicle his exploits, sometimes typing while leaning against a stone wall on a course. Little wonder that although Jones retired in 1930, Keeler did not publish his “authorized biography” until 1953.

The director, Rowdy Herrington, has made more exciting movies, including “Road House” (1989), legendary for its over-the-top performances by Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch and Ben Gazzara. “Bobby Jones” is more solemn, more the kind of movie you’re not surprised was financed by The Bobby Jones Film Company, and authorized by the Jones trustees, who also oversee lines of clothing and the like. It is also not astonishing, I suppose, that although the film mentions that Jones founded the Augusta National Golf Club and started the Masters Tournament there, and although a photo over the end credits shows Jones with the course’s favorite golfer, Dwight D. Eisenhower, there is no mention of the club’s exclusion of blacks and women.

To be fair, the movie isn’t really about Jones’ entire life; it focuses on his youth and his championship golf. I am not a golfer, although I took the sport in P.E. class in college and have played a few rounds. There are too many movies to see, books to read, cities to explore and conversations to hold for me to spend great parts of the day following that little ball around and around and around. I do concede that everyone I know who plays golf loves the game, and that most of them seem to derive more cheer from it than Bobby Jones does in this movie.

That Jones should obtain more pleasure than he does is all the more certain because the movie mostly shows him making impossible shots, at one point chipping the ball into the hole from close to the wall of a sand trap higher than his head. Walter Hagen spends a lot of the movie raising his eyebrows and grimacing in reaction shots, after Jones sinks another miracle.