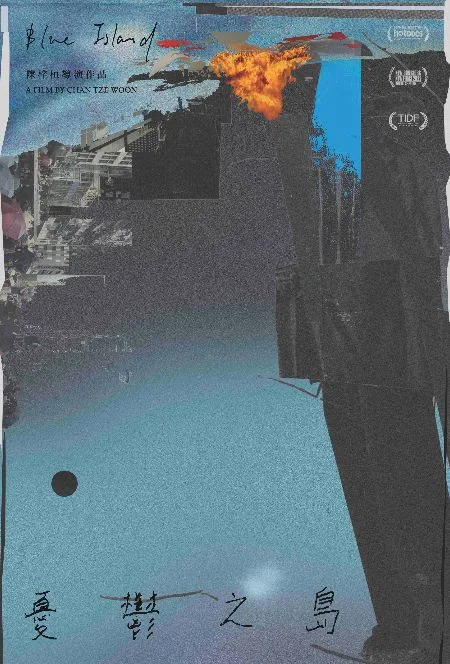

The makers of the moving but uneven Hong Kong protesters doc “Blue Island” seem to struggle with how they should dramatize their human subjects given the hostile (or at minimum, unfriendly) working conditions that led them to crowdfund their movie. “Blue Island” begins with a dedication to the 2,645 anonymous crowdfunding backers who made the movie possible, which hints at the difficulty of making a movie like “Blue Island” in contemporary Hong Kong. Still, the artful parallels that director Chan Tze Woon draws between contemporary and now middle-aged pro-democratic Hong Kong protesters often seem insubstantial given the movie’s thinly drawn narrative of historic events.

The ideal audience for “Blue Island” might already be so well-informed that they don’t need to know much more about pro-democracy protests in 1989, 1990, 2014, and 2019. But Chan’s movie would probably still have benefited from a greater sense of journalistic rigor. This isn’t just a matter of asking more follow-up questions (though, frankly, most documentary interviewers should): the testimony of older Hong Kong protesters could either be better contextualized with additional background information or more thoughtfully juxtaposed with conversations with younger protesters.

Chan reminds viewers of some fundamental parallels that unite Hong Kong protesters, both through on-screen text and on-camera interviews. One representative intertitle tells us that, in 1989, “nationwide crackdowns” resulted after 1.5 million Hongkongers protested in solidarity with pro-democracy mainland Chinese; the mainland government’s retaliation is likened to the passage of the National Security Law in 2020, one year after Hong Kong residents protested the passage of the Extradition Law. Also: the flight of 50,000 Mainlanders to Hong Kong, some 50 years ago, is compared with the exodus of 90,000 Hong Kong citizens following the passage of the National Security Law.

These clearly drawn parallels between the past and the present are most meaningfully developed when Chan presents younger protesters in (literal) conversation with their predecessors. In a concluding scene, Gen Z protester Kelvin Tam sits in a jail cell and talks with Gen X demonstrator Dr. Raymond Young about their respective feelings and beliefs. “Time will slowly erode your ideals,” says Young, speaking more clearly and directly than in many prior scenes, where he visibly struggles to explain his heavy and complicated emotions. Tam’s response is even better, if also too brief: “Even when we’re just filming, I’m terrified. Isn’t that messed up?”

Tam and the current generation of Hong Kong protesters are the real heart of “Blue Island,” so it’s especially hard to see their stories get less—or maybe just less meaningful—screen time than older demonstrators. It’s interesting to hear folks who protested in the 1980s or fled the mainland in the 1970s interact with Chan and his crew, like when Chan Chak-Chi—who became an exile from China in 1973—notes the mood, during the Cultural Revolution, was “not so fervent.” It’s not as exciting (or rewarding) to see Chan reduce dissidents like Kenneth Lam to their current discomfort. Lam struggles to put on his eyeglasses and also drinks too much wine at a reception after he tells us that “When we were young, we dreamt of a better world.”

Meanwhile, younger protestors—some of whom were born as recently as the mid- to late 1990s—are reduced to powerful, but ungenerous summaries of their experiences. In a later scene, dozens of protesters sit and either look at or past the camera while on-screen text tells us what they’ve been accused of. Some have been charged with “obstructing the police” (a district councilor) or “rioting” (a YouTuber); many are blamed for “conspiring to subvert state power.” These defendants are identified either by their professions or what they do in life: a high schooler; a musician; an actor; a gym owner; a nurse; a student. I wish I knew more about them.

“Blue Island” features a lot of great footage, but a lot of it either doesn’t hang together or flow seamlessly from one episodic scene to the next. There’s no question that Chan’s hit on something potent and essential when he notes the fundamental similarities between various Hong Kong protesters, but it often seems like there’s so a lot more that he could have asked or shown us, and it’s only a few follow-up questions away.

I understand why Chan wanted to include so much footage of his older on-camera subjects, but I also wish he’d pressed them for more thoughtful responses. I also wish “Blue Island” honored the efforts of its younger on-camera subjects by giving them a deeper focus. I’m sure Tam doesn’t mean to be critical of Chan or his crew when he says that, “It’s not tiring to insist that I did no wrong. But it’s exhausting to keep telling people I’m ok.” That last line is unintentionally damning, and it shouldn’t be.

Now playing in select theaters.