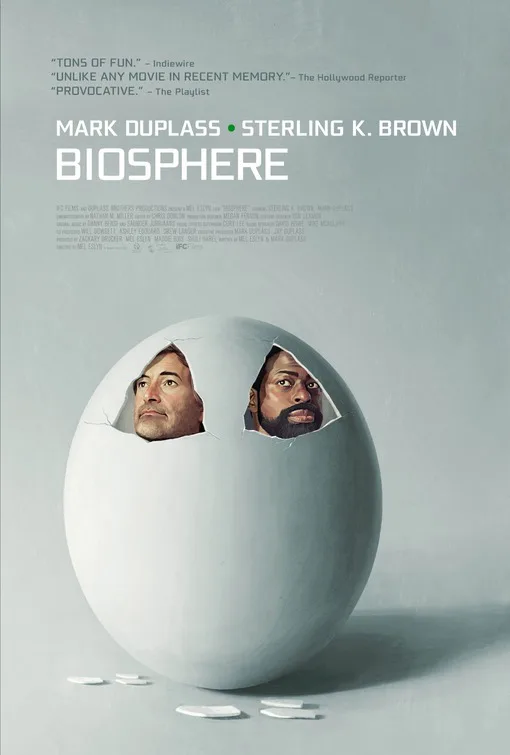

If you muted the soundtrack of the lopsided sci-fi parable “Biosphere,” about the presumed last two men on Earth, the movie might look better than it sounds. Not because “Biosphere” features spectacular special effects or because it’s visually impressive. Rather, this ponderous two-hander looks better when its co-leads, Sterling K. Brown and co-writer Mark Duplass, try to convey a manic, claustrophobic mood mainly through body language instead of grating, sitcom-style dialogue. Director/producer/co-writer Mel Eslyn also occasionally succeeds in reframing her two characters as parts of their cramped habitat. But there’s more schtick than speculation baked into the dialogue, which makes it too easy to dismiss this unfortunately stagey misfire.

“Biosphere” has a curious premise that’s briskly unpacked within the movie’s first half hour. [SOME ESSENTIAL SPOILERS FOLLOW] In that time, insecure Billy (Duplass) and overweening Ray (Brown) discover that they’re not only trapped in a biodome that is running out of food but also that one of the fish that they’re raising for their own dietary needs has suddenly and unexpectedly become a hermaphrodite. This evolutionary leap coincides with an even bigger plot contrivance: Billy’s also spontaneously undergoing intersex changes, which freaks him out and intrigues Ray, formerly a biologist. Somehow, these key plot developments aren’t the most unbelievable parts of “Biosphere.”

We soon learn that Billy used to be President of the United States, if only for 14 months. He doesn’t, or at least didn’t, share Ray’s progressive values, and while Billy’s never out-and-out compared to a Bush or a Trump, there are clear signs that his policies have had a similarly polarizing effect. The fact that even Billy cops to making rash decisions as POTUS says more about the filmmakers and their ideal audience than these characters, whose relationship is built around an unbelievable sort of present-tense camaraderie.

Yes, Ray, a registered Democrat, has regrets, including his tenure as the ex-President’s adviser, but he and Ray live in the now. They talk about their feelings, which are neatly labeled and broken down in ways that suggest that it’s not the situation at hand that’s funny, but the characters, who are both more suggestive as symbols than as psychologically or emotionally complex people.

Through a surplus of hand-holding dialogue, “Biosphere” presents a weirdly hollow sort of Utopian optimism, where the bonhomie between a Black and a white man says everything and nothing about the movie’s understanding of the “patriarchy,” as Duplass refers to his edgy protagonists in the movie’s press notes. Here, Billy and Ray follow what seems like an inevitable progression toward an unusual premise: Would you be able to able put aside your differences and repeatedly change your relationship with somebody you’ve known for years, first because of utilitarian necessity and then maybe some latent personal feelings?

The latter part of that character dynamic goes largely unexplored in “Biosphere” since so much dialogue indicates qualities in both Billy and Ray that their creators never seem interested in developing. Most anecdotes and tit-for-tat bickering only serve to establish the characters’ theories about their shifting relationship or their philosophical differences. You probably don’t know any real people who talk like Billy and Ray do, despite some load-bearing references to “Super Mario Bros.” Even two key scenes where Ray unpacks his heart’s contents, first with a fish and then to Billy, seem more like story outline placeholders than soul-baring monologues.

Granted, a good part of the appeal of “Biosphere” stems from its nature as a fantasy of what could be rather than what already is. Which might be why so much of Billy and Ray’s squirmy banter concerns their insecurities, though Billy’s feelings get unpacked at greater length, partly because he’s the chattier of the two men. Ray’s a doer while Billy’s a worrier; Ray has faith, while Billy tends to sulk and catastrophize. More importantly, the two men deliberately focus on their present dilemma—what to do about Billy and his body—which only partly opens a can of worms. Rather than dig into what’s specifically changing about their relationship, Duplass and Eslyn focus on armchair psychology and black-box speeches to explain away what’s really going on with these two men. Never mind why the world ended. What matters is Billy and Ray’s magical thinking, as well as their coy will-they/won’t-they tension.

The movie’s comedic climax is both the worst and the best scene: [ANOTHER ESSENTIAL SPOILER] Ray and Billy attempt to get to know each other a little more intimately but only wind up weirding each other out even more. This routine is mostly funny, thanks to Brown and Duplass’ frenzied slapstick chemistry. Unfortunately, this scene also drags on for so long, with too little comedic inflection or development, that it eventually feels like the best and only joke the filmmakers could think to tell. Maybe it plays differently if you cover your ears?

Now playing in theaters.