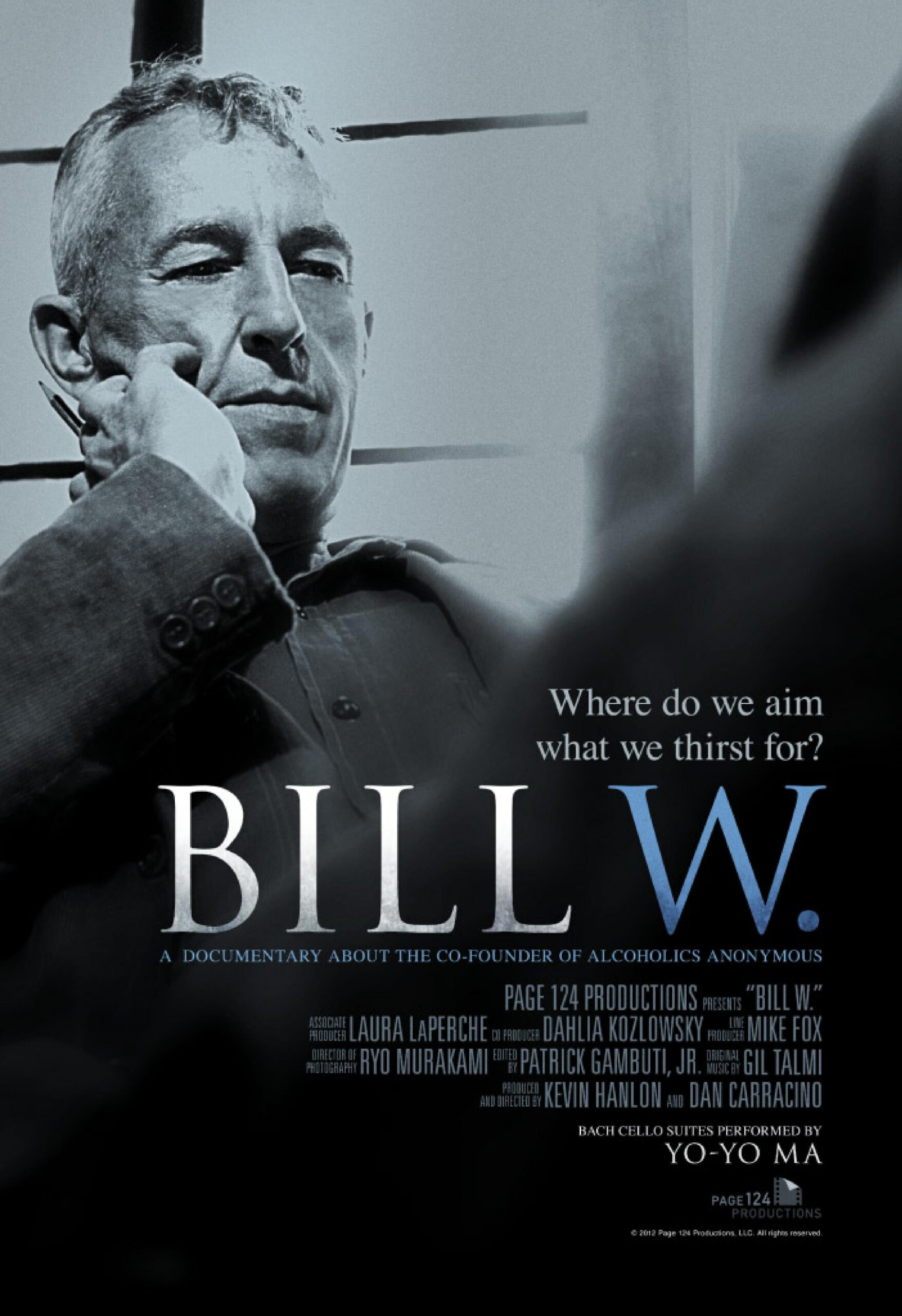

“Bill W.” tells the story of Bill Wilson and the organization he co-founded, Alcoholics Anonymous. What is most remarkable about AA is that for many alcoholics, it works; its current U.S. membership is estimated at 2 million. It has no leadership, it charges no money, it’s just rooms of former drunks, and a great many people find it helps them stay sober for (as the program says) one day at a time.

Alcohol is an addiction. Most people can drink moderately. Some cannot. They don’t choose to get drunk, but they learn again and again (to quote) that they are powerless over alcohol. To help them, AA uses not drugs, not psychiatry, not expert theories, but group meetings. There is a crucial moment in this film when Bill W., stranded in Akron, Ohio, after a business deal falls through, paces a hotel lobby with his eyes drawn to the cocktail lounge, and in desperation hears himself saying on the phone, “I need to talk to another drunk.”

That leads to his historic first meeting with Dr. Bob Smith, an Akron surgeon whose drinking was endangering his career and the lives of his patients. They began with some of the principles of the Oxford Group, a non-denominational Christian fellowship popular in the 1920s, and found they could stay sober by meeting with other alcoholics for mutual help. From their early experiences they distilled the “Twelve Steps,” which have since been borrowed by countless recovery programs.

This documentary is an assembly of styles. It incorporates such film footage of Bill as is available, and then uses actors to re-enact chapters in his story. The actors never speak; the voices heard are from tape recordings made by Bill W.; Dr. Bob; Bill’s long-suffering wife, Lois, and others. The period re-creations are detailed and convincing. We also see some current AA members, their faces in shadow, some of whom knew Bill before his death in 1971.

Bill was not a saint, and the film doesn’t hesitate to deal with his flaws. He cheated once on Lois, for example. He also notoriously experimented with LSD in the earliest days of that drug’s history, when it was legal and was thought to be a possible cure for addiction. He stopped, realizing a cure had to come from within.

Judging by this film, neither Bill nor Bob seems to have been particularly religious. The second step of their program calls for alcoholics to call on “a Higher Power as we understand him,” but the power is never identified, and the idea seems to have been realizing the power was not their own willpower. Some complain that AA requires members to believe in God, but it doesn’t, and that objection is sometimes joked about as “choosing to stay drunk for theological reasons.”

Bill was a tall drink of water, a craggy man from Vermont who had a knack for business but kept drinking himself out of success. Ironically, he was to found an organization that was once studied by the Harvard Business School as a model of nonprofit, self-perpetuating functionality. He probably could have made a lot of money by commercializing AA (the movie shows John D. Rockefeller as one of his early backers), but he never did. When members got together, that was a meeting. No dues or fees. The program was carried by oral tradition.

A key part of AA was anonymity: “Who you see here, what you say here, let it stay here.” Bill Wilson himself was not anonymous — that horse was already out of the barn — and his fame was such that Time magazine named him as one of the 100 most influential men of the century. Told he should be on a postage stamp, he said: “They’d have to show the back of my head.”