Love stories have beginnings, but affairs . . . affairs have endings, too. Even sad love stories begin in gladness, when the world is young and the future reaches out cheerfully in every direction. Then, of course, eventually you get Romeo and Juliet dead in the tomb, but that’s the price you have to pay. Life isn’t a free ride. Think how much more tragic a sad love story would be, however, if you could see into the future, so that even this moment, this kiss, is in the shadow of eventual despair.

The absolutely brilliant thing about “Betrayal” is that it is a love story told backward. There is a lot in this movie that is wonderful — the performances, the screenplay by Harold Pinter — but what makes it all work is the structure. When Pinter’s stage version of “Betrayal” first appeared, back in the late 1970s, there was a tendency to dismiss his reverse chronology as a gimmick. Not so. It is the very heart and soul of this story. it means that we in the audience know more about the unhappy romantic fortunes of Jerry and Robert and Emma at every moment than they know about themselves. Even their joy is painful to see.

Jerry is a youngish London literary agent, clever, good-looking, confused about his feelings. Robert, his best friend, is a publisher. Robert is older, stronger, smarter and more bitter. Emma is Robert’s wife and becomes Jerry’s lover. But that is telling the story chronologically. And the story begins now, with Robert and Emma fighting, and with Robert slapping her, and with Emma and Jerry meeting in a pub for a painful reunion two years after their affair has ended. Each additional scene takes place further back in time, and the sections have uncanny titles: Two years earlier. Three years earlier.

We aren’t used to this. At a recent public preview of the film, some people in the audience actually resisted the backward time frame, as if the purpose of the playwright was to just get on with the story, damn it all, and stop this confounded fooling around.

The “Betrayal” structure strips away all artifice. It shows, heartlessly, that the very capacity for love itself is sometimes based on betraying not only other loved ones, but even ourselves. The movie is told mostly in encounters between two of the characters; all three are not often on screen together, and we never meet Jerry’s wife. These people are smart and verbal and they talk a lot — too much, maybe, because there is a peculiarly British reserve about them that sometimes prevents them from quite saying what they mean. They lie and they half-lie. There are universes left unspoken in their unfinished sentences. They are all a little embarrassed that the messy urges of sex are pumping away down there beneath their civilized deceptions.

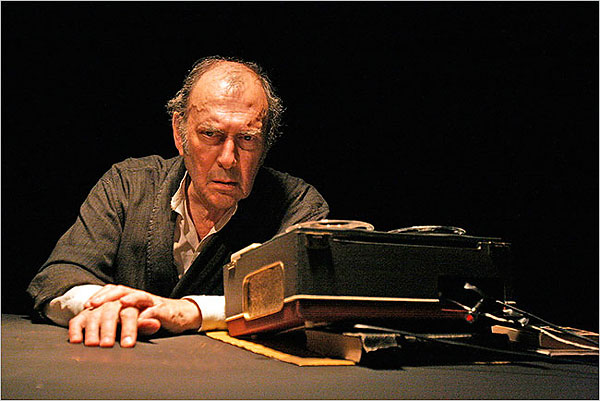

The performances are perfectly matched. Ben Kingsley (of “Gandhi“) plays Robert, the publisher, with such painfully controlled fury that there are times when he actually is frightening. Jeremy Irons, as Jerry, creates a man whose desires are stronger than his convictions, even though he spends a lot of time talking about his convictions and almost none acknowledging his desires. Patricia Hodge, as Emma, loves them both and hates them both and would have led a much happier life if they had not been her two choices. But how can you know that when, in life, you’re required by the rules to start at the beginning?