Bean is like a malevolent Ace Ventura in slow motion. Remember the cartoon character who went everywhere with the dark rain cloud hovering over his head? For everyone he meets, Bean is that cloud. Since so many slapstick heroes are relentlessly cheerful or harmless, his troublesome streak is sort of welcome.

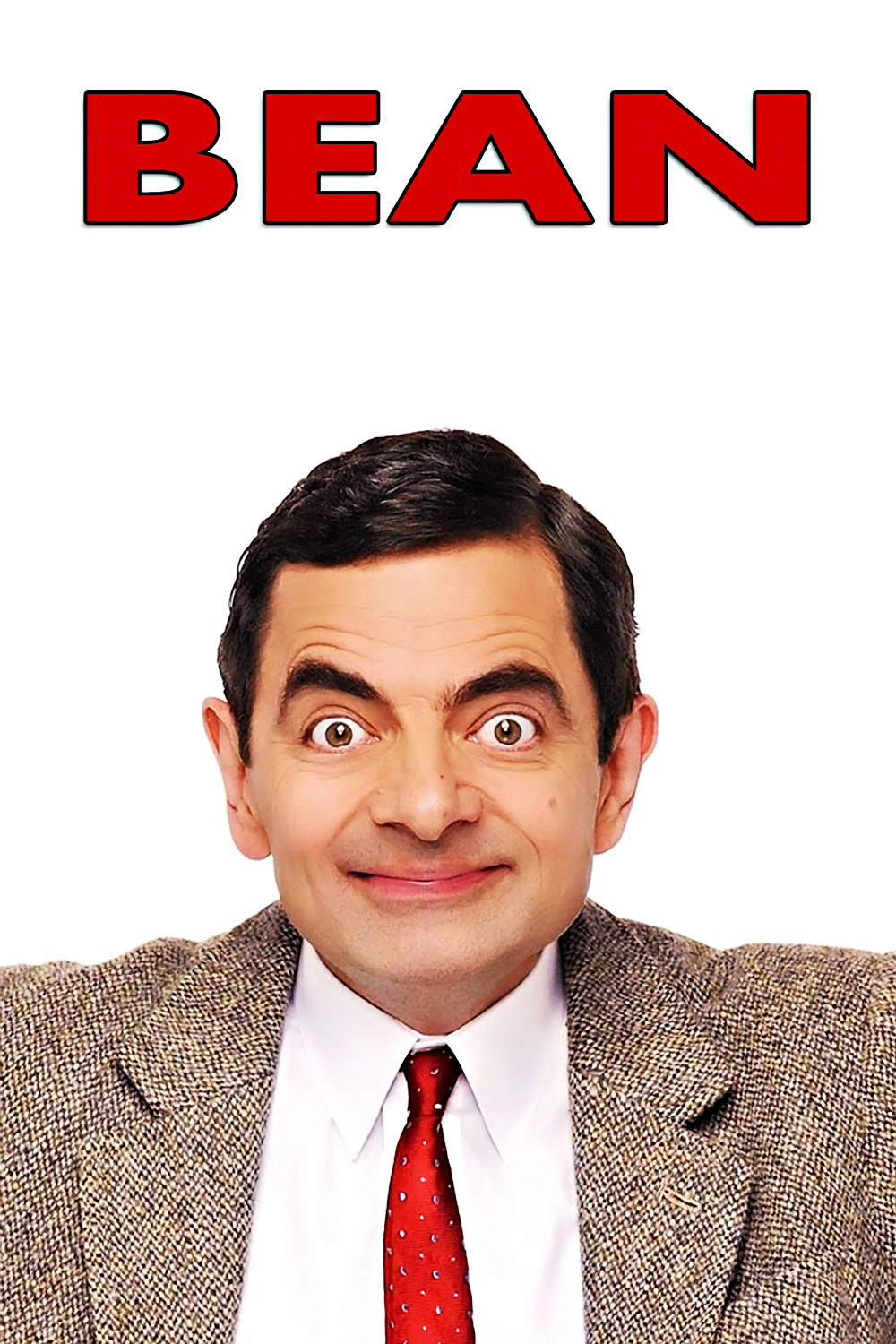

Bean, played by Rowan Atkinson, first came to life as the star of a British sitcom that quickly became the most popular comedy show in English-speaking markets all over the world. In America, where Bean hides out on PBS, he is not as well-known. Now comes “Bean” the movie, which arrives in the United States having already grossed more than $100 million in the U.K., Australia, Canada, etc.

Although America is the last market to play “Bean,” the film seems to have been tailored with an eye to Yank viewers; most of the action takes place in Los Angeles. The set-up is in London, where Bean is employed as a guard at an art gallery and is “easily our worst employee,” as the curator says at a board meeting where the first order of business is to fire him. When the ancient chairman (John Mills) vetoes that idea, the board gleefully ships Bean off to America as its representative at the unveiling of “Whistler’s Mother.” The famous painting has been purchased from a French museum by a rich retired general (Burt Reynolds), who is no art lover but hates the idea that the “Frenchies” own America’s most famous painting. Bean’s task will be to oversee the installation of the painting in L.A., and speak at the unveiling–tasks for which he is spectacularly unequipped.

The Bean character has his roots in the clowns of silent comedy, although few were this nasty. On TV, he scarcely speaks at all, preferring wordlike sounds and swallowed consonants, but here he blurts out the odd expression, and in one of the funniest scenes, gives a speech before assembled art experts. His adventures are a mixture of deliberate malice and accidental malice. (For example, when he inflates the barf bag on an airplane and pops it above the head of a sleeping passenger, that’s malice. But the fact that it was filled with vomit–that was an accident.) Bean’s host in the United States is a young curator (Peter MacNicol), whose wife (Pamela Reed) and children move out of the house after about 20 minutes of Bean. MacNicol hangs in there, as he must: His boss (Harris Yulin) has warned him his job depends on it. Bean goes on a tour of L.A., succeeding in speeding up a virtual reality ride so that it hurls patrons at the screen, and that’s benign compared to what he eventually does to “Whistler’s Mother.” The movie gets in some sly digs as the California museum prepares to market the painting with tie-in products such as T-shirts, beach towels and beer mugs. But most of the film consists of Bean wandering about, wrinkling his brow, screwing up his face, making sublingual guttural sounds and wreaking havoc.

Who is Bean, anyway? Like the Little Tramp, he exists in a world of his own, perhaps as a species of his own. He combines guile and cluelessness (he knows enough to use an electric razor on his face, but not enough to refrain from also shaving his tongue). He knows how to perform tasks, but not when to stop (can stuff a turkey, but gets it stuck on his head). And he is not, in any sense, lovable (the movie gets a smile with MacNicol’s attempt to tack on one of those smarmy moments where it’s observed that Bean means well; he doesn’t mean well).

There are many moments here that are very funny, but the film as a whole is a bit too long. Perhaps the half-hour TV form is the perfect length for Bean. When the art gallery episode has closed and the action shifts to a hospital operating room, I had the distinct feeling that director Mel Smith was padding. Maybe there’s a rule that all feature films must be at least 90 minutes long. At an hour, “Bean” would have been nonstop laughs. Then they added 30 minutes of stops.