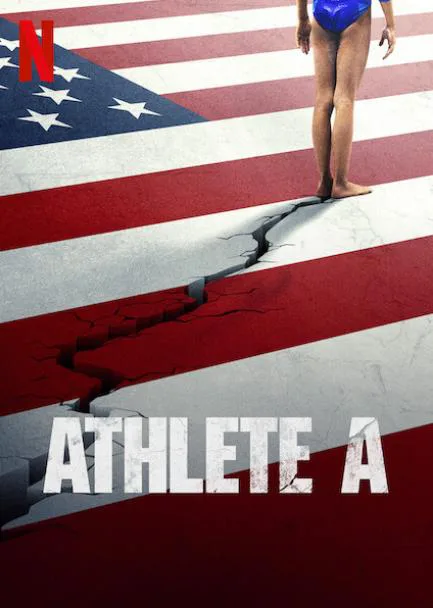

“Athlete A,” named for the then-anonymous gymnast whose complaint led to the first public disclosure of decades of abuse by Larry Nassar, reveals that the toxic culture of USA Gymnastics was about protecting the brand, not the girls. The selection and training techniques that produced champions also made the girls vulnerable to abuse, moving them to an isolated training facility in Texas where coaches alternated between telling them they were special and berating them for anything short of perfection. Coaches Bela and Marta Karolyi could be brutal, even slapping them for not measuring up. If the girls tried to complain, they were ignored or asked to sign non-disclosure agreements. And they knew that even asking questions meant risking not being selected for the Olympic team.

The “aesthetic” of female gymnastics competition changed after 14-year-old Nadia Comaneci’s “perfect 10″ gold in the 1976 Olympics. Before that, team members were adults, like the 20-something men’s team. Today’s world-class female gymnasts are young and small. Simone Biles, America’s most-medaled gymnast with 19 world titles, is 4’8”. The members of the Gold Medal US 2012 team, called the “Fierce Five,” were all between ages 15-18. Some of them were among the 500 young gymnasts molested by team doctor Larry Nassar.

Around the same time that the focus of the sport shifted from adult women to strong but cute little girls, the focus of USA Gymnastics shifted, as organizations often do, to money. Steve Penny joined US Gymnastics as head of marketing and then became CEO of the organization. His priority was sponsors and the organization’s “brand.” Child sexual abuse is bad for the brand and a disaster for sponsors. In violation of the law, not to mention his responsibility for the safety of the girls in his care or the most rudimentary obligations of humanity, he did not report the complaints about Nassar to the authorities. He also lied in saying that he had, assuring the parents of Maggie Nichols that he had it under control and cautioning that they could not say anything without risking the ability of the FBI to investigate. They believed him. And, her father admits, they kept quiet because they did not want to risk Penny’s keeping her off the Olympic team.

We know how this ends. We saw Judge Rosemarie Aquilina give Nassar’s accusers a chance to read their heartbreaking statements before his sentencing. Directors Bonni Cohen and Jon Shenk show us the story of the predatory monster, the brave survivors, and the heroic reporters of The Indianapolis Star. But they want us to see more. Monsters cannot prey for 29 years without a failure of oversight and accountability. Cohen and Shenk show us the many factors and failures that contributed to the abuse over decades, including an almost cult-like environment, separating the girls from parents, teachers, and friends, constantly measuring their bodies and performance, demanding obedience, and making the appearance of excellence more important than the health and welfare of the girls.

The three moments that hit me the hardest were images I had seen before but now, thanks to the careful, utterly compelling context of the film, I understood them in a new way. The first was the iconic moment from the 1996 Olympics, when Kerri Strug won the gold for the US Team with an extraordinary vault, almost perfectly executed despite a severe injury. It was one of the highlights not just of the Olympics but of any athletic event of the year, and she was universally praised for her courage and dedication, called the ultimate competitive athlete. Watching it again, narrated by Jennifer Sey, author of Chalked Up, about her experiences as an elite gymnast, I no longer saw courage and dedication. I saw a young woman in terrible pain, Karolyi not checking to see how she was, just calling out, “You can do it!”

The second, just glimpsed in passing, was a sign that said “Women’s Gymnastics.” It’s a reminder that we overlook just how young these competitors are. And the third was McKayla Maroney’s scowl at the 2016 Olympics when she received her silver medal. It was a humorous meme at the time, even imitated by then-President Obama. But knowing she was abused by Nassar hundreds of times, including the very first time she saw him, suggests that the scowl may have been more than a pout over coming in second.

Cohen and Shenk show us that the Karolyi style of training was designed to keep the girls quiet and compliant, focused on their physical strength by keeping them emotionally unsure. Away from parents, teachers, and friends, the Karolyis were everything to the girls. The young athletes were taught to follow orders. The Karolyis weighed the girls every day and called them “pigs” if they gained weight. It is not a coincidence that Nassar used candy to help gain their confidence.

One former gymnast says, “The line between tough coaching and abuse gets blurred.” This may be what it takes to win gold at the Olympics, but is it worth the cost?

Now streaming on Netflix.