To be born here is to be born into hell. That must have happened for more than 300 years, because no one would ever want to come to live here. “Araya” tells the story of life on the remote, barren Araya peninsula of Venezuela, where Spanish conquistadors found salt about 1550. Salt was treasured in Europe, to the misfortune of those whose lives were devoted to it.

This astonishing documentary, so beautiful, so horrifying, was filmed in the late 1950s, when an old way of life had not yet ended. It was the belief of the filmmaker, Margot Benacerraf, that the motions of the salt workers became ritualized over the decades, passed down through the generations, and that here we could see the outcome of the endless repeating of arduous tasks that would destroy others.

The salt cake is taken up from the floor of a shallow marsh, loaded into flat-bottomed wooden boats, broken up, carted onto land in wheelbarrows and loaded into 120-pound baskets to be balanced on the heads of workers who trudge up the side of an ever-growing pyramid to deposit it. At the top, a man with a rake shapes each mound into a towering, geometrically perfect form. Now it is ready to be hauled away in trucks.

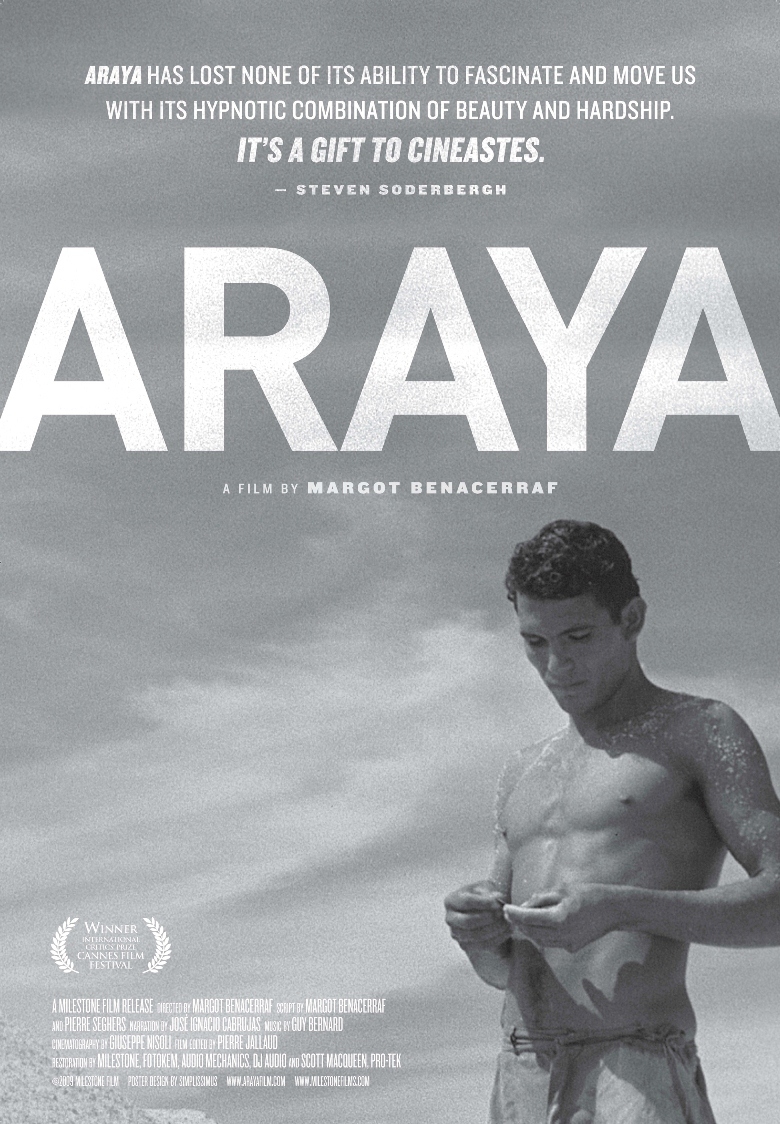

The workers, bronzed by the sun, all muscle and sinew, work in a blazing sun in a land where nothing grows. Food comes from the sea and from corn meal that is carted in. They live in small rude shacks. They get their water from a tank truck. Some work all day. Some work all night. Such is their life.

And just such a phrase, “such is their life,” is used in the doc’s narration, which seems to hover in detachment above the sweat on the ground. I imagine Benacerraf’s purpose was to make the toilers of Araya seem heroic in “a land where nothing lives.” Where the sun is hot and pitiless so often, it becomes a mantra. The effect is odd at first, but then we grow accustomed: The idea is to see these people not as individuals but almost as a species evolved to take salt from the sea, build it into pyramids, watch it hauled away and start again.

We learn something about salt along the way. It was so prized that the Spanish built their largest overseas fortress on the peninsula to guard it. The men who died building it were the first of many who paid for salt with their lives. The working conditions of the salt workers were brutal; their feet and legs were ulcerated by the salt, and if they faltered, they had no income. Their existence is agonizing, and we feel no regret that their way of life is ending. They have been reduced to robots. Small wonder the film contains so little dialogue. Yet these people lived and died, and we had salt in our shakers. It would be too sad if they were not remembered.

This black-and-white doc, so realistic in its photography, so formal in its words, played at Cannes in 1959 and shared the critics’ prize with Alain Resnais’ “Hiroshima, Mon Amour.” Benacerraf , a Venezuelan director born in 1926, is still alive and much honored. Her work was almost lost over the years. Now the doc has been restored to pristine beauty by Milestone Films, and is on a national tour of art venues.