There are no angels in “Angels & Insects,” only insects, and a strange mid-Victorian family named the Alabasters, who seem to model themselves on insect behavior. The mother is a plump, pale creature, swaddled in yards of white cloth, who collapses on the nearest chair to be fed and coddled by her family. Like a queen bee, she is fecund, pumping out new Alabasters between headaches.

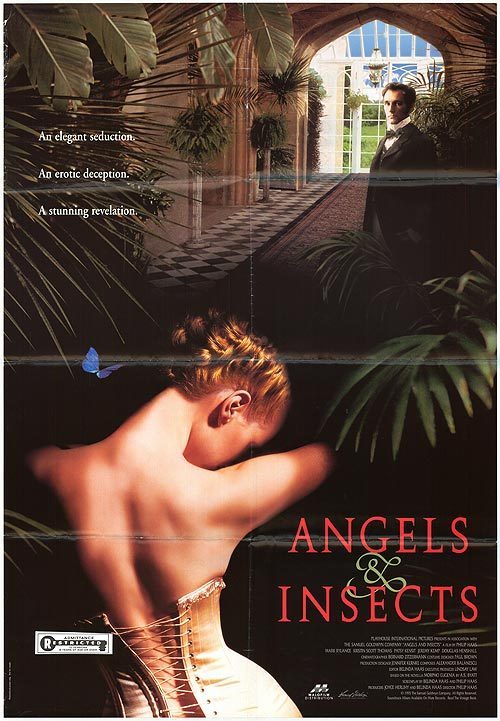

Into this household comes a dour Scots outsider named William Adamson (Mark Rylance). He has returned from 10 years in the Amazon collecting rare specimens that have all been lost in a shipwreck – all but one precious butterfly, which he presents to Sir Harald Alabaster (Jeremy Kemp), who is obsessed with insects. It is shortly after Darwin’s first publications, and Sir Harald is fascinated by the process of natural selection.

So is the film, which is based on a short novel named Morpho Eugenia by A. S. Byatt, and which uses its human characters to play out the ruthless strategies and laws of the insect kingdom. Adamson is invited to stay as a guest at the Alabasters’ country house, and organize Sir Harald’s insect collection. We cannot help noticing that the Alabaster women themselves seem part of an exotic collection; their dresses are made of bright reds and shocking blues, or bold yellows and blacks. In their elaborate hairdos and on their hats they wear flowers, berries, fruits, birds and even eggs.

The most alluring of the women is the blond, ripe Eugenia Alabaster (Patsy Kensit), with masses of pre-Raphaelite hair. In an early scene she runs sobbing from a ball. Her supercilious brother, Edgar Alabaster (Douglas Henshall), accuses Adamson of having insulted her, but in fact Eugenia is in tears because her fiance has recently killed himself. Slowly, cautiously, like a potential victim testing a possible web, Adamson positions himself closer to Eugenia, and eventually asks for her hand in marriage. Amazingly, it is accepted – even though he is a penniless man of ordinary family, and she is rich and high-born.

All of this time, a drab little ant has been busily working among the gaudy birds and bees. She is Matty Crompton (Kristin Scott Thomas), a poor young woman who is tutor to the family. She is attracted to Adamson, but he scarcely notices her (she tells him angrily, “you do not know if I am 30 or 50”). He does notice her superb drawings from nature, however, and her studies of an ant colony.

More of the devious and shocking plot I will not reveal. The story works like the trap of some exotic insect, which decorates the entrances with sweet nectars and soft fragrances, and then prepares an acid bath inside. Notice the countless touches that show the harsh pecking order in mid-19th century Britain: the servants who turn to face the wall when a master or mistress passes; the cocky arrogance of Edgar, who feels birth has given him the right to insult his social inferiors; the repressed anger of old Sir Harald, whose insect collection replaces a great many other things he would love to pin wriggling to a corkboard.

The movie has been directed by Philip Haas, and adapted by Haas and his wife, Belinda. They are not shy about using the rich verbal material of their source, A. S. Byatt; butterflies in a conservatory are like “colored air.” This is the first film I can remember in which anyone is attacked by moths; Adamson expresses himself in cautious evasions and toadying compliments, like an intellectual Uriah Heep; and when the plot’s trap finally springs and a secret is discovered, the movie makes a point of not explaining exactly how this is accomplished. The closest it comes is when Miss Crompton tells Adamson, “There are people in houses who know everything, yet remain invisible.” “Angels & Insects” works best if you’re familiar with its world, the country homes of the British upper classes in the mid-19th century. That world, Henry James has said, was for its fortunate inhabitants the most pleasant that human civilization has produced.

Ah, but it had its secrets. “Angels and Insects” is like the dark underside of a Merchant-Ivory film; in one scene, we visit a sunny, pastoral clearing in the woods, and lift up a rock to see the plump, slimy little slugs and larvae beneath, dining on each other.