The summer of 2020 reignited the promotion and consumption of antiracist readings. It was a year when the public deemed it “especially important” to read the work of Black authors, especially, the work of Black authors discussing Black plight. Director Cord Jefferson, in his feature debut, “American Fiction” (based on Percival Everett’s novel, Erasure), unpacks the qualifying characteristics and limitations of mass market white interest in Black stories.

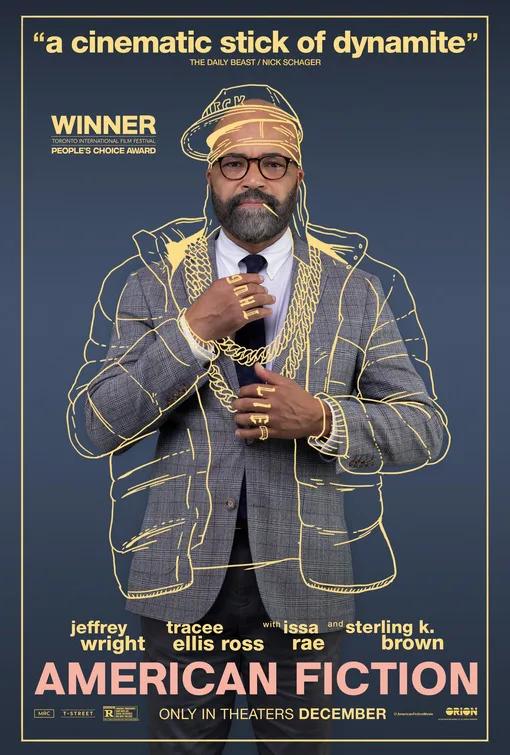

Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) is an author and college professor. He is published but not famous, struggling to sell his latest work to a publisher. Prompted by his uphill climb to publish, instigated by the media attention granted to Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), a Black author with a middle-class upbringing whose novel centers on inner city Black women, Monk decides to build a fantasy. He writes a joke novel, My Pafology (later indignantly renamed to Fuck) under the pseudonym Stagg R. Leigh, a faceless persona of a wanted fugitive. Thrown together without care for craft or attention to detail, and rife with Black stereotypes, Monk intends his book as more of a cathartic release of frustration and a middle finger to the publishing world. The manuscript, however, is met with exuberant attention by a publishing house’s insatiable desire to elevate this “genius” and an overzealous movie producer’s desire to win acclaim.

Resentful to that response and juggling uneasy family dynamics back home, Monk is left to navigate the conditions under which his work is deemed desirable and marketable, as well as the personal demons that prevent him from moving forward in his own story. Stagg R. Leigh is revered while Thelonious Ellison is stagnant, digging his nails into the sand to keep himself and his family from slipping out to sea.

“American Fiction” is a thoughtful, although heavy-handed, film. The strength of its thesis successfully bonds the film together. And yet, there are more than a handful of moments, both comedic and dramatic, that plead for a reaction. A shot of Monk, after engaging in heated debate with Sintara about the white gaze, standing before Gordon Parks’ famous photograph of The Doll Test is just a sample of the film’s coarse approach to inspiring emotion. With so much consideration put into Monk’s existential crisis, these moments of sympathetic begging yank away the feeling of authenticity, and “American Fiction” turns into a frustrating tug-of-war.

Amidst Monk’s struggle to cope with the acclaim of his faux novel, the story of his family becomes a drama of its own. Death, sibling rifts, and his mother’s declining health only deepen Monk’s crisis of conscience about identity and issues. On the whole, these family sequences are effective, blending with the reality of Monk, thereby enhancing the burden of the fantasy of Stagg. Sterling K. Brown gives a spirited performance as Monk’s younger, reckless, and bawdy brother Clifford. Questions of historically stringent perspectives on Black manhood are well explored between Clifford as a gay man, Monk as a hyper-intellectual, and the implied presence of their late father, a man who is often recalled for his uncaring ways.

However, “American Fiction” often treats its Black women as accessories to the story. His sister, Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), has little screen time, essentially functioning as a vessel for exposition before exiting to introduce the film’s first turning point. His girlfriend, Coraline (Erika Alexander), is there as moral support, uplifting Monk when Clifford tears him down. She is also the vehicle through which we can see Monk in his personal life, outside of writing or caring for his mother. Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor), their live-in homeworker, is installed as a maternal replacement as his mom, Agnes (Leslie Uggams), declines. And finally, Sintara is there simply to be a foil to Monk’s philosophy. This sidelining of the Black female characters might have gone overlooked if Monk was the only character given the spotlight. But while “American Fiction” is his story, there is a great deal of effort to provide Clifford with history, nuance, and a full narrative arc.

The mass market desire for Black life in art to be equivalent to Black strife is not a new concept; Jefferson’s film taps into the motivating context of that bias in today’s world. As Monk reveals the intricacies and blatant stains blemishing the fabric of the literary market, Jeffrey Wright gives an incredible, nuanced performance, nailing Monk’s swallowed feelings and the emotions bubbling beneath his intellectualized, repressed responses. He stews in just about every scene he’s in, and, in the few where he starts to lash out, Wright makes clear the pain beneath the petulance. He’s certainly unlikable. He’s often rude and condescending, but we root for him anyway because moments of learning follow in the footsteps of his flaws. And, simply, we also think he’s justified: his frustrations often match our own.

“American Fiction” trips over its own feet in its final act, stumbling between daydream sequences and multiple storylines before finding a final, underwhelming resolution. But the attentive lens that the film devotes to its concept and themes is what will be remembered. Jefferson’s film succeeds best when it’s being thoughtful, even as it often tries too hard to implore you to react. It carries a sensitive, important declaration in its bones: A testament to the versatility and validity of where Black art meets Black life, and a sharply pointed finger at the many institutional factors that keep it, and its creators, restrained.

In theaters today.