In 2008, a General Motors automobile factory in Dayton, Ohio was shut down—another victim of the cratering economy. Among the witnesses to its final hours were documentarians Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert, who not only filmed outside of the plant and interviewed a number of the now-displaced workers buy also supplied some of those employees with tiny camcorders to capture footage of the final cars rolling off the assembly line. (The resulting short, “The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant” [2009] would go on to be nominated for an Oscar.) As it turns out, that was not quite the end of the story for the plant—a few years later, it was purchased and reopened in an effort to bring manufacturing jobs back to the area again. It sounds like the happiest of endings but, as Bognar and Reichert’s latest film, “American Factory,” demonstrates in an ultimately striking manner, that did not quite prove to be the case.

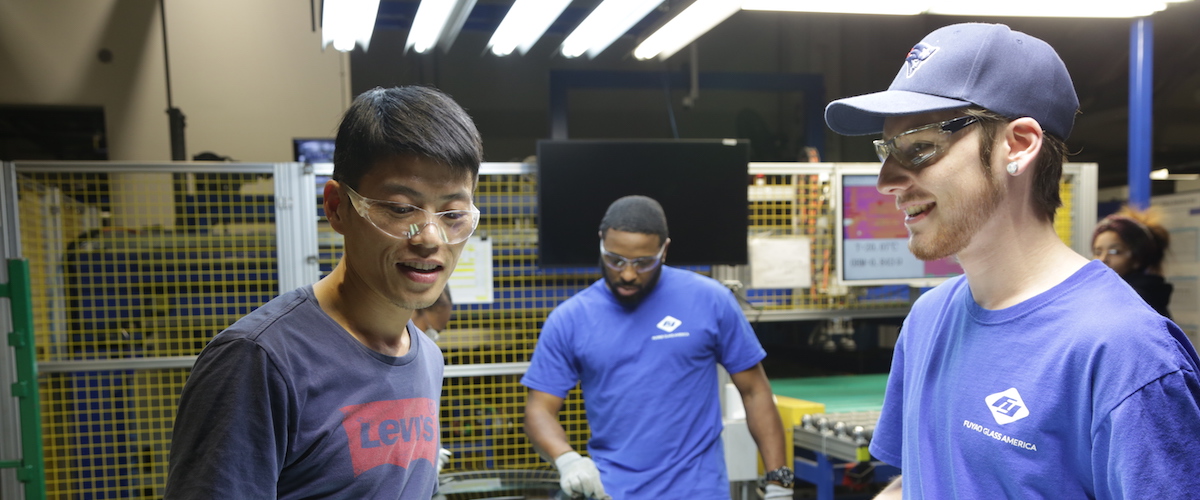

The factory was purchased in 2014 by Cao Dewang, a Chinese billionaire who chose to reopen the plant as the US outlet for Fuyao, his automobile glass-making company. As conceived by Dewang (known in his company as Chairman Cao), the plan would be to hire up to 2,000 workers and augment them with about 200 additional workers brought over from China to help with retraining. In announcing his plans for the factory, Cao talks about how he hopes to change how Americans view the Chinese and demonstrate that they could work together in harmony after all. Is this really possible? To try to cover the cultural gap, we see the newly transplanted Chinese workers undergoing training sessions to help them better interact with their American counterparts—they seem amazed, for example, that Americans are allowed to dress more casually and can even joke out loud about their President. As for the American workers, a number of whom had worked at GM, some may have their doubts but most are willing to overlook that in exchange for a steady paycheck, even it is half of what they were making a few years earlier at GM.

At first, it seems like things might actually work out, especially as each side’s prejudices start to recede. The trouble is that there are innate differences between the Chinese and American attitudes toward work that simply cannot be overlooked. As Dewang belatedly discovers, the approach that made Fuyao effective in China—in which workers are seen more as cogs in a machine than as individuals, overtime and working on weekends is considered mandatory and safety regulations and protocols are not strictly observed—will not work here. To try to bridge the gap, some American managers are brought over to China to observe how their system works, but attempts to implement what they’ve witnessed don’t go over well. As Dewang is driven to frustration by the plant’s underperformance, the workers—upset by the stagnant wages and uptick in workplace injuries—begin to contemplate joining with the United Auto Workers, a move that Dewang vows will lead to him closing up shop for good.

As in their past films, Bognar and Reichert employ a quieter approach to the material that lets it unfold without telling you how to feel. That being said, the first half feels a little on the soft side, as some scenes play almost like a spin-off of “The Office” and others seem to go out of their way to show everyone in the best possible light. But once the focus begins to shift from the culture clash to the fight over an upcoming vote on unionization—with Cao paying “consultants” over a million dollars to lecture workers at length on the horrors of unions and then telling them that “you have a voice”—the film begins to toughen considerably as it shows how pro-union workers are being targeted by management for daring to speak out. Although the specific story that “American Factory” may not ultimately be a happy one for many, it is nevertheless a stirring testament to the importance of the labor movement in this country and how it remains as important as ever even as the face of industry changes irrevocably.

Because it is the first film to be released by Higher Ground, the production company formed by Barack and Michelle Obama that signed a highly publicized deal with Netflix, “American Factory” will no doubt find an audience far larger than the typical documentary focusing on the contemporary labor movement. It provides a snapshot of the struggle between labor and management that is both timeless and distinctly of its time. Even more surprisingly, it does so in a manner that is often engaging and entertaining, considering the subject matter. You can almost imagine Bogna and Reichert returning to the plant again in a few more years to complete their trilogy. Then again, considering the implications for the near future found in the final scenes, maybe not.