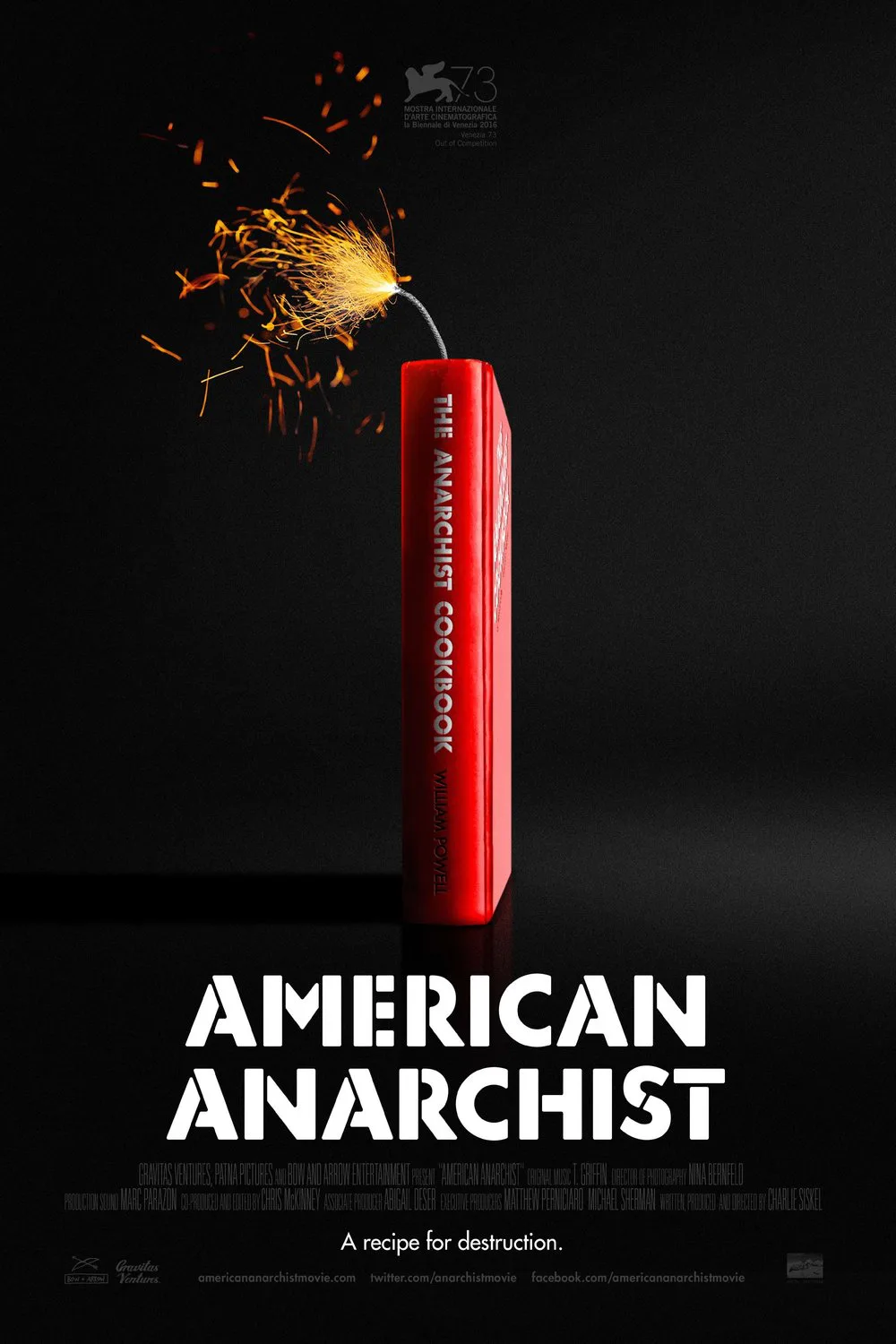

Charlie Siskel’s “American Anarchist” is an intriguing film about an infuriating man. Like Errol Morris’ “The Fog of War,” the documentary centers on an individual who essentially launched a weapon of mass destruction and had to live with the consequences. Yet whereas “The Fog of War”’s subject, former Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, was candid and eloquent, staring the viewer straight in the face (thanks to Morris’ “Interrotron”), the eyes of Siskel’s interviewee are averted toward his interrogator with more than a glint of reluctance. William Powell is not at all what one would expect the author of 1971’s The Anarchist’s Cookbook to look or sound like at age 65. He speaks in a British accent, spawned from his childhood in England, and looks more like a seasoned professor than an aging hippie. When Siskel starts asking him questions about the notorious book he wrote when he was 19, Powell appears as baffled as the audience by the fact he had anything to do with it. His answers aren’t evasive so much as they are muddled, considering he partakes in more hemming and hawing than a marathon of Warren Beatty performances.

As a former field producer on Michael Moore’s “Bowling for Columbine,” which is briefly glimpsed here, Siskel shares his mentor’s desire of catching his subject in a moment of self-revelation, guiding him toward it by illuminating the blind spots in his perspective. This creates a testy dynamic between him and Powell, causing the man at one point to scold the director for being “deliberately provocative.” Of course, the same could be said of Powell’s book, which compiles various diagrams and recipes culled by the author from military manuals, with section titles such as “How To Make Tear Gas In Your Basement” and “Railroad Sabotage.” Siskel grounds the film’s early scenes in the historical backdrop of Powell’s youth, a time when the Vietnam war had led countless citizens to believe that their government was out of control. The parallels between then and now are frighteningly apparent, with the fierce spirit of that era’s protesters embodied in the Black Lives Matter movement, so well-documented in Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis’ “Whose Streets?” Burning down convenience stores after police fail to be punished for killing unarmed black youth is deemed by members of the movement as a “strategic revolutionary act,” with the key factor being that the private property is unoccupied at the time of its destruction. The message advocated in Powell’s book is much more troubling, as articulated in lines like “People are helpless without a gun” and “Respect must be earned by the spilling of blood.”

After Powell claims that he hasn’t read the book since he wrote it, Siskel hands him a copy and asks him to recite selected passages, including the above lines that the author now believes to be “rubbish.” Though the word “anarchist” is included in the book’s title, Powell stresses that he wrote every page entirely on his own, without being under the influence of any particular movement. He felt that since the military and various radical groups already knew these destructive tactics, the general public had a right to that knowledge as well, citing Lincoln’s belief that the American people have the right to overthrow their own government. The tragic flaw in Powell’s conviction is the fact that it places far too much trust in people. We see a montage of YouTube clips with kids using the book’s recipes to nearly blow themselves up in what could be regarded as “America’s Dumbest Home Videos.”

The Anarchist’s Cookbook is nothing more than the product of an idealistic mind that mistakenly believed the public would embrace its instructions as a tool to fight against evil, rather than be used by those who, like Heath Ledger’s Joker and the character’s real-life doppelgänger in Colorado, “just want to watch the world burn.” Powell, who passed away a year after filming on this project began, spent the last three-and-a-half decades of his life in self-imposed ignorance of the catastrophic effect his book had on generations of Americans, having lived entirely abroad with his wife, Ochan. Siskel unleashes a string of statistics to illustrate how the book’s righteous call for bloodshed has empowered everyone from homicidal teenagers and abortion clinic bombers to member of ISIS, all fueled by the shared belief that society has forgotten them. The copies of his book found in the houses of these terrorists leaves Powell filled with remorse, which he notes “is different from regret.” Ochan is more forthright in her thoughts: “We all do dumb things, but not all of us put it into print.”

The grand irony of Powell’s life is that he went on to spend the majority of his adulthood as an educator devoted to helping children who, like himself, have “emotional problems.” His move to and from Britain as a kid caused him to feel like a perpetual outsider, building up a frustration that resulted in Powell committing acts that, as an adult, he conspicuously underplays, such as how he “gently pushed a teacher’s car into a tree.” Siskel waits until the film’s last moments to reveal that Powell had been fondled by a teacher in boarding school, a horrific episode that, if anything, suggests why he felt the driving need to arm those who feel powerless. Lyle Stuart, the book’s publisher, comes across as a sensationalistic hack in Powell’s stories, allegedly staging a smoke bombing raid at the author’s press conference. After Stuart bought the rights for $10,000, Powell moved on with his life, and has been attempting to escape his past ever since. On numerous occasions, an anonymous group would unearth the book to prevent him from getting hired at various schools. Finally, Powell decided to put a statement on Amazon.com in which he denounced the book, and thirteen years later, published an op-ed piece at The Guardian where he expressed the same feelings. These acts, while well-intentioned, underline how Powell did the absolute bare minimum to prevent his book from being in print. After California senator Dianne Feinstein spoke out against the book, Powell reached out to her via e-mail, but the “out of office” message he received back discouraged him from pursuing the matter any further.

“American Anarchist” presents us with a young man who believed he was living in the apocalypse, and whose book has gone on to have an apocalyptic effect on society. Powell should be commended for his efforts to do good later in life, but his refusal to clean up the mess from his youth is puzzling and maddening in the extreme. His decision to leave the U.S. is sort of like Shane’s decision to leave the farmhouse in George Stevens’ classic western, had Shane chosen to leave all his guns in the valley.