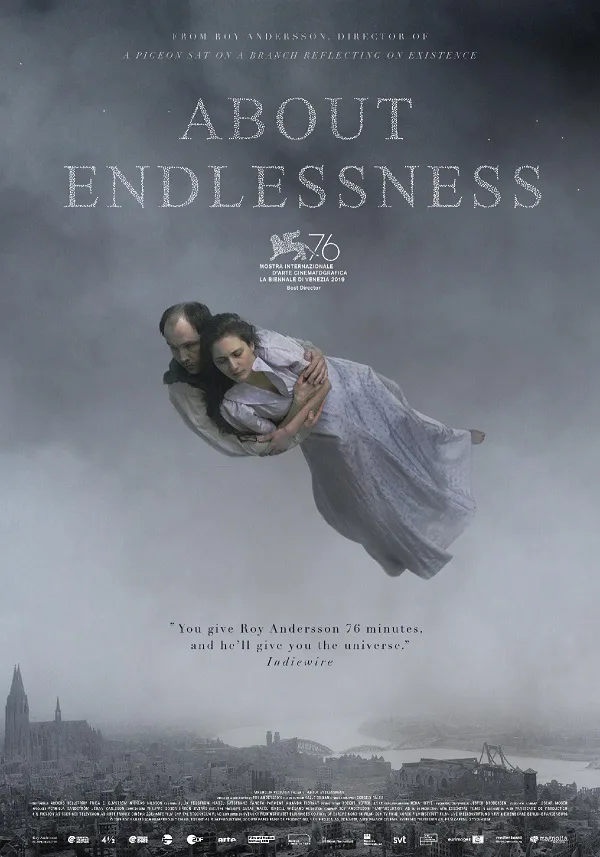

Although it begins with a shot of a couple in each other’s arms, floating over beds of gray clouds, “About Endlessness” is one of the least fanciful of Roy Andersson’s films. There’s less of the deadpan surrealism that tinged his prior, singular movies—which include a trilogy made between 2000 and 2014 comprising “Songs from the Second Floor,” “You, the Living,” and “A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence“—which may be seen as a good thing. Given that one of the fruits of that deadpan surrealism was a grievously ill-advised bit concerning African slaves in “Pigeon,” that could be considered a good thing.

I saw this picture for the first time in Venice in 2019, and here’s what I reported from there, for this website.

It’s rather kind of the Swedish director Roy Andersson to bring in a film called “About Endlessness” at under eighty minutes. A lot of directors could really abuse the latitude that title implies.

The endlessness Andersson shows here is rather light (the movie opens with a shot of a couple floating above a formation of gray clouds) and related to the idea of eternal return. “There was a man who did X,” “There was a woman who was X,” the female narrator announces, and the screen shows a perfectly composed single shot, the camera never moving, in which an invariable pale character enacts the described action or an ironic variation of it. The overall effect is a cross between a mordant New Yorker cartoon and a tableau from a Karel Zeman film. Andersson ought to approach Brian Cox to appear in one of his films; he is exactly the physical type for them. If ever a movie could be called insouciantly profound, “About Endlessness” is it.

On second viewing, it was the insouciance that on occasion stuck in my craw. In one of Andersson’s immaculately composed living tableaus—which manage to somehow look unfussy, despite clearly been near-obsessively contrived to the last frame—a man with no legs is in the corridor of a metro station, playing a mandolin. The narrator notes that the man had lost his legs to a landmine, and goes on to note, “it made him very sad.” One hesitates to invoke a vulgar phrase ending in the word “Sherlock,” but this is the sort of instance that underscores the sometimes too-porous border between dry and glib.

Nevertheless, one feels grateful overall for Andersson’s vision and visions. One can luxuriate on the pastel shades of his frames, which start from a base off gray and cannily place bits of cream and blue in strategic portions of the shot. He’s very fond of showing curved alleyways or roads. On one of them, a Christ figure undergoes a station of the cross in modern dress while figures from other vignettes in the film yell for him to be crucified. This is part of a narrative thread in which a priest loses his faith and torments himself—and his therapist. Down one other turn in the road, three cheerful young women pass by a café and start spontaneously dancing to a song by the Delta Rhythm Boys that’s coming from that establishment’s sound system. The “endlessness” of the film encompasses a lot of absurdity and disappointment, but its notes of grace sound the loudest.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.