In the final weeks of World War II, the conquering Soviet Army occupied a Berlin in ruins and did what occupying armies often do, raped and pillaged. There was nothing to stop them — least of all their officers, who knew that after years of relentless battle it was useless to try to enforce discipline, even had they wanted to.

“A Woman in Berlin” is a diary written at that time and published some 15 years later. Its author, who identifies herself as a journalist, was anonymous. The book’s publication in 1959 inspired outrage in Germany, where the idea of German women cooperating somewhat with the Soviets was unthinkable, and in Russia, where it soiled the honor of the Red Army.

In that time, in that place, women were raped. “How many times?” asks one of another, and they both know the subject of the question. The diary and film are about how the author attempted to control the terms of her defilement by deliberately seeking out a high-ranking Russian who would act as her protector. Who is to say this was wrong of her?

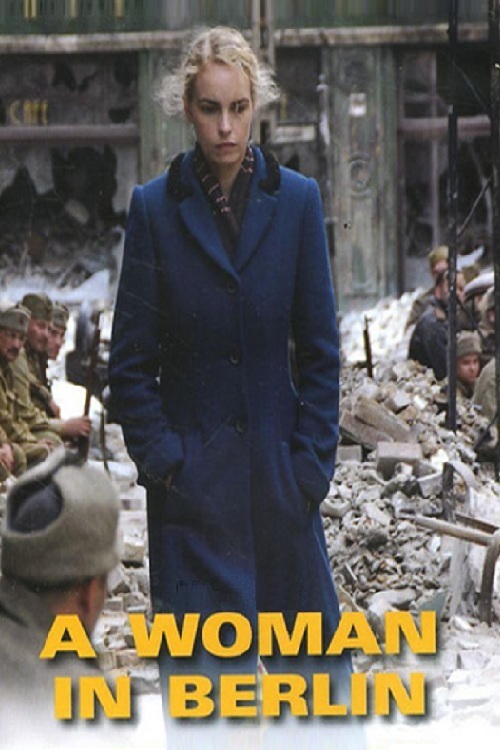

The woman, Anonyma, is played by Nina Hoss, who in two other films released here in the past year, “Yella” and “Jerichow,” has emerged as a strong, confident actress with innate star quality. She is seen here in an early shot at a party, elegantly dressed, ruling the room, a proud Nazi, proposing a toast to the brave boys at the front. At the time, it appeared Germany would conquer Europe.

By the end of the war, her husband has disappeared in battle, and she is camped out with other women in the remnants of a bombed-out building. They are exhausted, dirty, hungry, frightened. They were all raised in the comfortable middle class, and now find themselves scrambling like animals for food and shelter. The obvious sources of food and drink are the Russians. Most of them are crude, even bestial, but then the women cannot be choosers.

Anonyma had luck seducing a lieutenant and then sets her sights on a major, Andrei (Yevgeni Sidikhin) who is the top-ranking officer in sight. He’s also by far the most complex. He resists her come-on at first, perhaps because he’s fastidious, more likely because he simply doesn’t see himself as that kind of man. Something unspoken passes between them. They grow closer. Yes, she profits from their liaison, and yes, he eventually takes up her offer. But for each there is the illusion that this is something they choose to do.

What little I know about war suggests that sometimes it comes down to a choice between two dismaying courses of action. Some people would rather die than lose their honor. Most people would rather not die, particularly if their deaths would not change anything. Anonyma and Andrei are people with similar sensibilities, similar feelings, now divested of the illusions they presumably brought with them into the war.

That is the movie’s insight, and the book’s, too, I assume. This isn’t a love story in any palpable sense. It is a story about how things were. “A Woman in Berlin” finds no particular point in the story, and no one is heroic in any sense. The woman and man make the best accommodation they can with the reality that confronts them. There are several subplots involving other women and other soldiers, and one involves a woman who is subtly pleased by the power her body gives her. Well, she’s not the first such woman, or man.

The film is well-acted, with restraint, by Hoss and Sidikhin. The writer and director, Max Faerberboeck, employs a level gaze and avoids for the most part artificial sentimentality. The physical production is convincing. The movie is just enough too long that we realize we’ve already seen everything it has to observe.